Dr Jake Barnes introduces a British Academy report, launched on 29 July and what it means for those innovating local policy making to deliver and scale solutions to local issues.

On Tuesday 29 July the British Academy launched a new report Governance to Accelerate Net Zero. The report draws attention to the importance of governance for transformative change and argues that enhancing eight governance mechanisms can accelerate progress towards net zero. In this blog Dr Jake Barnes introduces the report and reflects on its value for those innovating local policy making to deliver and scale solutions to local issues.

Governance to Accelerate Net Zero

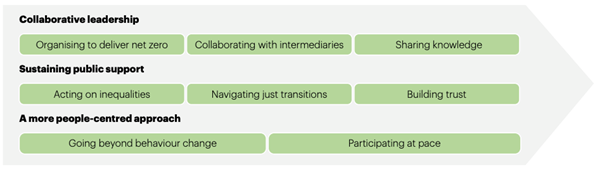

In 2021 the British Academy started a new programme to clearly articulate why governance matters for net zero and how good governance practices can support achieving national targets. This report summarises its findings. It argues that net zero is a complex and systemic challenge that requires collective action across different levels of government, sectors, and communities and it sets out how ‘good democratic governance’ can be supported to accelerate progress on net zero. The report is intended for political and policy leaders across the UK: it aims to help them navigate complex decisions and connect with diverse communities to drive urgent collective action. The research for the report included ten projects, sixteen papers, and insights from over 200 stakeholders. At the centre of the report sit eight governance mechanisms, grouped in three main areas, each thought capable of accelerating progress towards the UK’s net zero by 20250 target (figure 1).

Figure 1: The British Academy’s governance accelerators for net zero (page 4)

Collaborative leadership

Collaborative leadership is seen as central to enabling coordination and collective accountability. Mechanisms to support leadership are thought to involve a focus on organising to deliver change rather than focussing solely on delivery itself. This involves effective coordination across government scales to address policy ambiguities and short-term thinking. Collaborating with intermediaries – diverse organisations that sit between others – as key to supporting collaboration across places, scales and sectors. Whilst developing and sharing knowledge is thought vital to informing decision-making.

Sustaining public support

To garner and sustain public support the report argues that leaders need to prioritise trust, fairness and effectiveness. Associated mechanisms include acting on inequalities to bring visible benefits to communities, navigating just transitions by developing transparent and inclusive governance process and building trust through accountable governing bodies and practices.

A more people-centred approach

Finally, the report brings attention to developing a whole system, people-centred approach and contrasts this with an individualised, technocratic and technology centred approach. Mechanisms to facilitate this include going beyond behaviour change approaches to support early and sustained participation in decision-making, and facilitating participation at pace: the report calls for the improved use of public participation approaches to create more impactful policy and greater accountability.

Implications for those innovating local policy making to deliver and scale solutions to local issues

The report makes an important contribution to contemporary national debates on the climate emergency at a time when net zero targets are increasingly being challenged. But it also offers valuable insight for those working on developing more effective policy making to deliver and scale local solutions. Below I highlight four points.

Unpacking governance

First, the report does a very good job at unpacking the often hazy concept of governance and its implications for contemporary policy making. It clearly highlights the multiple public, private and third sector stakeholders involved in contemporary decision-making and delivery and their independencies across places and scales. It also crucially, highlights the politics involved, correctly highlighting how “contestation and conflict are a normal part of transitions”. In doing so the report brings to the fore how challenging it is for contemporary leaders at different scales and places to effectively navigate towards a broadly desired, yet highly contested societal goal such as net zero. For the LPIP programme, surfacing the politics of change provides recognition of why innovating local policy is challenging.

Recognising place diversity

Second, the report goes beyond place blind or place agnostic policy making that is a hail mark of a liberal market economy and Westminster politics and calls for greater recognition of place diversity. It highlights the need to adapt governance arrangements to place as well as the solutions it helps generate. Solutions can rarely, if ever, be seen as blueprints. Instead, it is better to see solutions as ideas to be taken up, translated and embedded in different places. Whilst the LPIP programme may recognises this, the report provides a platform on which to make the case to national policy-makers.

Power of collective thinking

Third, the report highlights the power of collective, non-market-oriented activity and the contribution of social innovations to a more sustainable future. Too often national approaches focus near exclusively on technology-based market-driven innovations as the principle means of achieving change, whilst neglecting community-based ideas for doing things differently that can make a real difference to people’s lives. In most instances experimentation within LPIP regions involves social rather than technical innovations. Nonetheless, questions remain about how to scale social innovations to achieve wider change within and beyond LPIP programme whilst working within a discourse that appears largely uninterested.

Tackling inequalities first

Fourth, the report highlights the need to tackle longstanding socio-economic inequalities as a foundation for (a) sustained public support in new or reformed governing processes and (b) in the necessary remaking of basic societal systems around housing, energy and transport. Too often this comes as an afterthought or add on, rather than the focus. If the growing populist backlash to action on net zero is to be effectively tackled, it will mean delivering tangible improvements to disadvantaged communities sooner rather than later. The LPIP programme appears to intuitively recognise how greater enabling of participation increases trust but it is less clear to what extend a focus on tackling inequalities can be the first step in a new approach to remaking systems of provision.

There’s definitely more to explore here. In many ways, the British Academy’s report provides the big picture—offering a crucial foundation for those of us in the LPIP programme. The LPIP programme, in turn, is where we get to put these ideas to the test. One might criticize the report for not offering specific “solutions,” but in reality, there are few simple answers to today’s governance challenges. The real value lies in identifying practical actions that can be adapted and used across the UK to improve how we work. This is precisely the purpose of the LPIP programme: to experiment with the very participatory and inclusive policymaking that the report advocates for.

This blog was written by Jake Barnes, BA Innovation Fellow.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.