In this blog, Dr Matthew Lyons summarises the LPIP Hub Evidence Review: Living and Working Sustainably in a Greener Economy.

Context

The impacts of climate change are being felt across the world in increasing severity and frequency. As of 2024, temperatures were currently 1.28 oC above preindustrial levels. Nature in the UK is also under threat with wildlife having declined by an average of 19% since 1970, with nearly one in six species threatened with extinction.

The international community has set obligations to deliver net-zero by 2050 with interim targets in 2030 and 2040. Alongside goals to curb emissions there is a separate international movement to address biodiversity loss. The UN has designated the 2020s as the ‘Decade of Ecosystem Restoration’ to prevent, halt, and reverse ecosystem degradation worldwide. Central to this international effort is the United Nations Environment Programme.

The UK Government has been an early adopter of net-zero policy and has made great progress. The UK Government has committed to the overarching goal of net-zero by 2050, Scotland has its own target of net-zero by 2045. Within the overarching goals there are interim targets and sector specific targets. Current goals are for a net 68% reduction in emissions by 2030, and 95% clean energy generation by 2030.

This evidence review sits in a series of other LPIP evidence reviews covering the following thematic areas: Communities in their places; Cultural Recovery; Innovation; Local Economy; Skills; and Felt Experiences.

This evidence review considers the academic literature, grey literature and policy documents to identify the burning questions and key challenges for sub-national actors in achieving a more sustainable, greener economy.

Key Concepts and Burning Issues

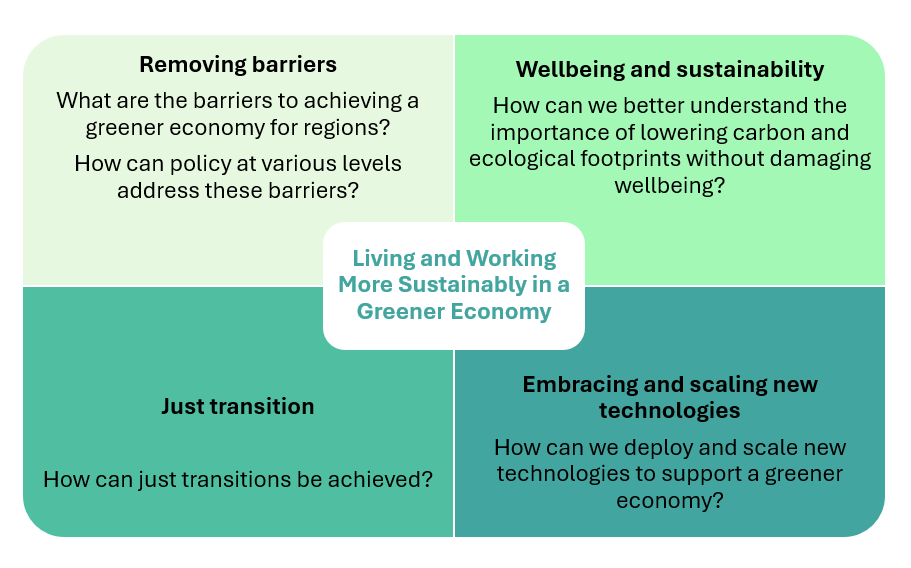

The burning questions surrounding living and working sustainably in the green economy are outlined below. These questions aim to uncover the key challenges and opportunities for local, regional and national governments in achieving a sustainable, greener economy. Addressing these questions is vital for developing targeted, effective and inclusive policies that can meet the distinct environmental and economic needs of different areas, fostering both sustainable growth and more sustainable development.

Key Findings

Nature recovery is underrepresented in environment policy

In the UK, action to support nature recovery is underdeveloped, with weaker legal targets and significantly less funding despite its role in climate resilience. While new policy has mandated Biodiversity Net Gain in relation to development, it lacks the rigour and enforcement needed to drive large-scale ecosystem improvement.

Key takeaway: Nature recovery goals and metrics should be incorporated into local action plans. It is important to consider the protection and recovery of the natural environment alongside the decarbonisation of the economy and society.

Regions have differential strengths and weaknesses

Regions have different industrial compositions and geographies which in turn means that they have different strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in reference to net zero, nature recovery and living sustainably.

Key takeaway: Policy should seek to work with the grain of the regional economy. Some regions will have different timelines to achieving net zero which must be recognised.

Early interventions are cheaper in the long run

Earlier interventions will prevent greater costs in the long run in terms of environmental, social and economic impacts. However, long-term policy action is often constrained by short-term policy agendas from central government, short-term funding pots limiting long-term planning, and pressures from businesses to prioritise short-term economic goals over environmental ones.

Key takeaway: The opportunity cost of delay, both in terms of nature recovery and decarbonisation is high and not routinely considered in policy agendas.

Decarbonisation can be achieved with a place-sensitive approach

Decarbonising the economy can have uneven impacts on communities. However, there are good examples of managing industrial transitions to minimise social and political upheaval through community engagement and targeted policy intervention.

Key Takeaway: Change needs to reflect context and community interests. It is important to plan for a gradual transition which allows places, cultures and communities to adapt. Successful interventions involve local buy-in and engagement from a range of stakeholders and residents.

Local, regional and national governments have different but complimentary roles

Multi-scalar governments play important roles in providing funding and infrastructure as well as shaping consumer choices and activity. Successful multi-level environmental policy requires long-term planning, alignment across government levels, empowerment of regions and communities, and institutional place-based partnerships. However, the asymmetric power dynamics of the UK governance system can reduce ambitions and the pace of change on the ground.

Key takeaway: Finding the right balance between decision makers allowing local and regional authorities to have support from national level actors can enhance the impact of environmental policies.

Examples of partnership working in the UK

Transport innovation in Manchester

Challenge: Like many urban areas, Manchester is facing high levels of air pollution, which is estimated to cost 1,200 lives annually, and congestion, which is estimated to cost the city-region over £1.3bn annually.

Solution: Transport policy at the national level reflects the evidence that higher levels of active travel and public transport use have the potential to reduce carbon emissions and improve the liveability of communities across a range of factors. Greater levels of active transport have benefits for health, community and retail.

Partners: To implement the various transport innovations listed it required partnerships from different levels of government as well as private sector and third sector partners. At the government level, the UK DfT provided funding and regulatory support for infrastructure such as Metrolink. At the city-region level, the GMCA and TfGM worked together on strategy, planning and funding. Local councils collaborated and consulted on implementation and community needs. Private sector partners such as Stagecoach, Kelois Amey and Siemens were involved in implementation. Community groups and third sector organisations like cycling charity Sustrans were also involved in supporting project plans.

Manchester Bee Network Buses. Source: Image is CC 4.0 to use. Attribution Transport for Greater Manchester

Net-Zero Power in Teeside

Challenge: Teesside has an industrial history and as such is one of the UK’s highest emissions regions. The region hosts high emissions ‘hard-to-abate’ sectors including chemicals and cement production. Without the development of viable alternatives increasing net-zero regulations will lead to closures and economic hardship in the region.

Solution: The Net-Zero Teesside Power is a gas-fired power station with carbon capture technology which aims to produce 742 megawatts of low carbon power. The project aims to enable heavy industry in the region to cut emissions without ceasing operations.

Partners: The project is led by BP with a consortium of industry stakeholders including TotalEnergies and Equinor. The partnership is coordinated with the East Coast Cluster and in partnership with UK Government and was (2020) backed by investments such as Carbon Capture Infrastructure Fund (CCSIF).

Impact: The project aims to capture up to 2 million tonnes of CO2 per year. NZT power estimates it would create 3,000 construction jobs and require 1,000 employees during operation. Northern Endurance Partnership estimates suggest the East Coast Cluster could create 25,000 jobs annually from 2030.

Teesside Petrochemical works: Wikipedia CC 2.0 Source: Stephen McKay

Challenges and Future Research

The evidence review has identified some areas where further research could add value and fill gaps in the literature, shaping policy and practice in future:

- Removing Barriers: Future research could seek to better understand these barriers and how policy can help to overcome them.

- Just Transition: Future research could seek to understand the scale of potential shocks in UK regions and evaluate how policy could support a socially acceptable transition.

- Understanding Indirect Impacts: Future research could map these indirect impacts to better understand the often spatially blind nature of policy interventions.

- Policy Mapping: It is still difficult to understand the powers available to different regions and devolved nations to address climate and environment goals. Devolution has led to an ad-hoc arrangement of different powers being attached to places such as the Trailblazer regions, combined authorities, metro mayors and local authorities. An important exercise would be to understand the powers and resources that are available to tackle the different aspects of sustainability set out in this report.

Conclusions

The review has highlighted examples of successful policy interventions both within the UK and internationally, and the main contextual points are that:

- Moving towards a greener economy presents differentiated opportunities for regional development policy and practice.

- Different places face different challenges in transitioning to sustainable development.

- There is a complex hierarchy of powers and policy levers that operate at different spatial scales making it impossible to avoid place-based practice and experiment for success. As such, demonstrating the importance of the LPIPs.

Download the report – LPIP Hub Evidence Review: Living and Working Sustainably in a Greener Economy.

This blog was written by Dr Matt Lyons, Research Fellow, City-REDI, University of Birmingham and the lead for Living and Working Sustainably in a Greener Economy, LPIP Hub.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.