By Judith Martinez Estrada

Judith Martinez Estrada.

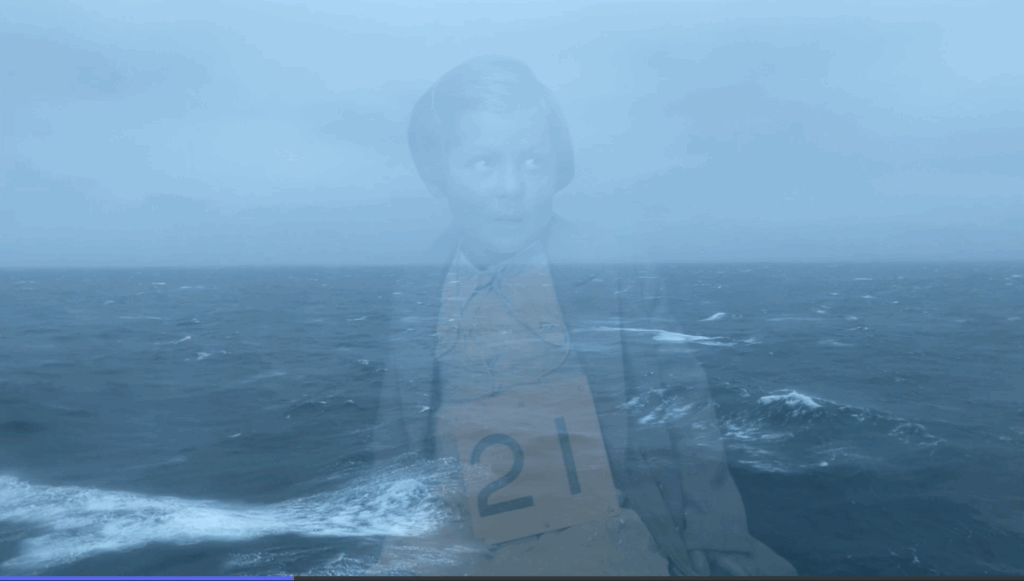

Ephemeral Landscape n.4. 2025.

Re-imagined landscapes featuring historical archival images. UV inks on aluminium.

120cm wide x 70cm high.

All stories have a beginning

This story starts at a gravesite. To be more specific, it starts at the exhumation of Juan Costalago Dueñas, a man who was assassinated on September 9, 1936, in Orillares, a small rural community in the region of Soria, Spain.

His exhumation took place in October 2022. At the time, I had been researching the mass graves of The Spanish Civil War for my PhD, and documenting the exhumation formed part of my scholarly fieldwork. This was facilitated by Emilio Silva, president of La Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica/The Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH). Silva believes that attending an exhumation allows us to bear witness and bring to light crimes that were intended to remain silent.

On the day of Juan Costalago Dueñas’ exhumation, I met Professor Monica Jato from the University of Birmingham. Professor Jato, who I am sure will not mind me calling her Monica for this post, was undertaking research for her own work. I mention the exhumation, because this chance encounter with Monica led me to gaining further knowledge surrounding the crimes of The Spanish Civil War, and learning how these extended beyond that of the executions that took place during the three years of terror, to other events that altered the lives of innocent people and children.

Amongst these was the mass evacuation of children from The Basque Country to The United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Catalonia, Russia and the Americas in 1937. The catalyst for this exile was the bombing of the town of Guernica in April 1937. The indiscriminate killing that resulted from this attack forced parents to make the sacrifice of being separated from their children as a question of safety and survival. Sadly, some of these children never saw their parents again.

In the months that followed the exhumation at Orillares, Monica and I developed a bond that extended over both our research and interests, and it soon became apparent to us both that we wanted to collaborate on a project that would somehow enable the retelling of the experiences of these children. This is how the project honouring the lives of the children of the war was born.

The Memory as Transgenerational Care research project was established by Monica at the university, and after almost a year of planning, I returned to Spain and The U.K to commence work on the creative component for the project. Monica, who is the project lead, had arranged for community engagement workshops in Mondragon in The Basque Country and Southampton in The U.K. We also visited and documented archives and locations that were of importance and symbolic significance to the stories of the exiled children, and worked with historical memory group Intxorta 1937 Kultur Elkartea, based in Mondragon to gather additional resources. This was taxing work — but the thoroughness and attention to detail established by Monica together with Julia Monge, Juan Ramon Gerai, and Nati Roa, from Intxorta, and Carmen Kilner from the Basque Children of 37 Association U.K, created a solid foundation for the project. This has made me appreciate the importance of teamwork for this kind of project to succeed.

The outcomes from this research, fieldwork and workshops, informed the artwork for the Sea of Shadows exhibition at El Instituto Cervantes in Manchester (2024) and Orratz-Begia / El ojo de la aguja / The Eye of the Needle exhibitions in Mondragon (2024) and Guernica (2025).

Judith Martinez Estrada.

Ephemeral Landscape n.3. 2024.

Re-imagined landscapes featuring historical archival images.

UV inks on aluminium. 150cm wide x 100cm high.

Judith Martinez Estrada.

The Unknown Path I. 2024.

Photo-media featuring archival images from personal photo albums.

1.3 metres wide x 5.8 metres high each.

Sublimation prints on textile.

All stories find their narrator

When I was eight years old, my family migrated to Australia. From what I can remember, this was not something my father and mother discussed with my sister or me. It was an unexpected move, and while they had probably been planning it for a while, it certainly took me, to say the least, by surprise. One day we were playing with our neighbours in Moratalaz, a neighbourhood in Madrid, the next we were on-board an Air-France flight to Sydney, and on the day after that, we were in the suburbs of Western Sydney, in the scorching Australian summer sun.

When I was first told of the story of the exiled Basque Children, I felt a sense of empathy and solidarity towards them. While my migration experience from 1981 cannot, and should not in any way, be compared to the cause that led to the exile of these children, there are elements that I could understand: Being separated from your loved ones, your home, and your environment against your will is difficult. More so if you had just experienced what these children had — their forced displacement is one marked by history. When these children were placed onboard The Habana, most had faced inexplicable danger and loss.

When creating this body of work, I realised that it was important for me to experience the same landscapes and seascapes as these children and I set out to retrace their journey by travelling from Bilbao to Southampton by ferry. During the 28-hour journey, I tried to imagine what they might have been thinking, fearing, hoping for, imagining. The journey did become frightening at times — especially when I realised that I was surrounded by a massive sea, with no horizon line in sight, and an enveloping darkness coming from both the sky and the depths of the ocean seemed to swallow the boat.

The motion is another aspect that I was not prepared for, and as the ferry rocked with the waves, I imaged the little bodies of these children, moving in unison with the ship and the ocean. After all this, there was safe harbour: the coastline, which was as alien to me in 2023, as it would have been to these children in 1937, became a sign of hope. I documented this experience at it became part of The Children’s Veil piece, which is a textile and film installation.

Judith Martinez Estrada.

The Children’s Veil. 2024/25

Photo-media featuring archival images from West Glamorgan Archives.

Sublimation print on cotton. 6 metres wide by 5 metres high.

Video. 13.20 minutes.

https://app.frame.io/reviews/bd07147a-c067-4e6d-a43c-e5fbd8e6778c/df42946f-1884-4ee0-810e-5292f21ffce6

Working with historical photographs depicting these children’s journey and experiences was a privilege, as was getting to know some of the surviving boys and girls, and their descendants during workshops in The Basque Country, Spain, and Southampton in The United Kingdom. Their stories were full of hope. The images they kindly allowed me to use in the installations depicted many emotions, events, adventures, but also spoke of their hardships and sadness. It is apparent that these children had experienced so much from such an early age, yet, their resilience is something that was visible and felt every step of the way.

All stories have an ending, but not all endings are final

The artwork created for The Memory as Transgenerational Care project explores the experiences of displacement of the exiled children through a series of photo-media, textile, video and print installations that formed part of the Sea of Shadows and the Orratz-Begia / El ojo de la aguja / The Eye of the Needle exhibitions. The latest iteration of the project is now exhibiting at the Euskal Herria Museum and the Gernika Peace Museum, in Guernica, The Basque Country, Spain. It will be on until march 2026.

The exhibitions serve as both memorial and tribute, acknowledging the sacrifice, strength, and adaptability of the displaced children and their families, while also drawing connections to contemporary refugee experiences.

It has been an honour to be able to tell, through creative interpretation, the stories of these children. I believe that when dealing with narratives based on sensitive historical accounts, it becomes the duty of the artist to retell these with respect and empathy. I am grateful for being entrusted with these stories and also for the generosity of the children, who are now well into their 90s, and their families, for allowing me to feature their personal photographs in the artwork. I would also like to thank The West Glamorgan archive in Wales for the use of their historical photographs used in The Children’s Veil.

As the exhibitions take place, we are approached by others who have similar stories. Stories that they wish to tell and for which we will be honoured to be the custodians.

Judith Martinez Estrada

The Unknown Path II.

Photo-media featuring archival images from personal photo albums.

90 cm wide x 2.4 metres high each.

Sublimation prints on textile.