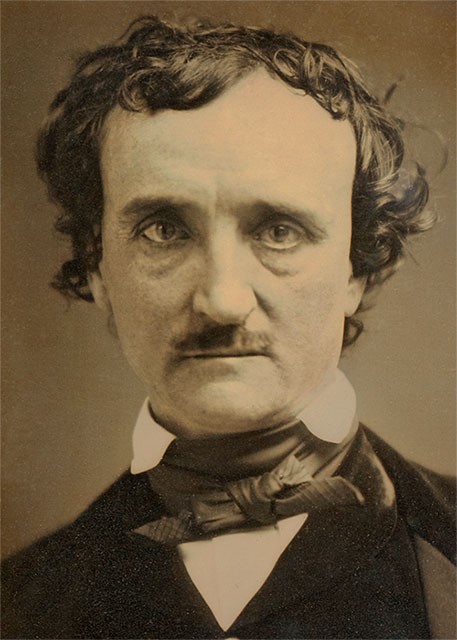

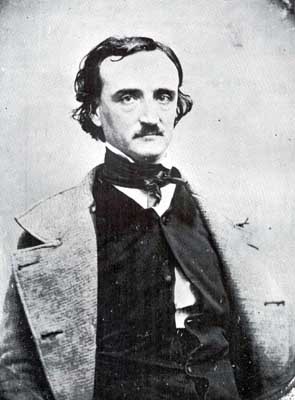

T.S. Eliot, writing in 1948, observed that although Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) had undeniably possessed a powerful intellect it was merely that “of a highly gifted young person before puberty.” In spite of Poe’s ability to dazzle and terrify, he maintained that “[t]he forms which his lively curiosity takes are those in which a pre-adolescent mentality delights.” (T.S. Eliot, ‘From Poe to Valéry’ in To Criticize the Critic and Other Writings (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), p 35) Eliot concluded that Poe’s sprawling fascination with everything from new technologies to scientific methods for solving crime, from cryptograms to mesmerism, from interior decoration to the exploration of the South Seas, had left his oeuvre not only hopelessly unfocused but also largely inconsequential. Instead of the creations of a great author, in his estimation Poe’s poetry and fiction amounted to a tiresomely juvenile bag of tricks of no serious interest to any discerning reader.

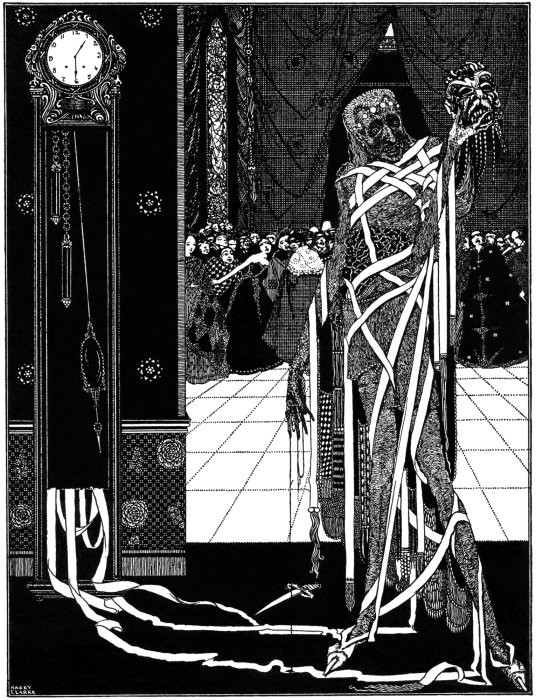

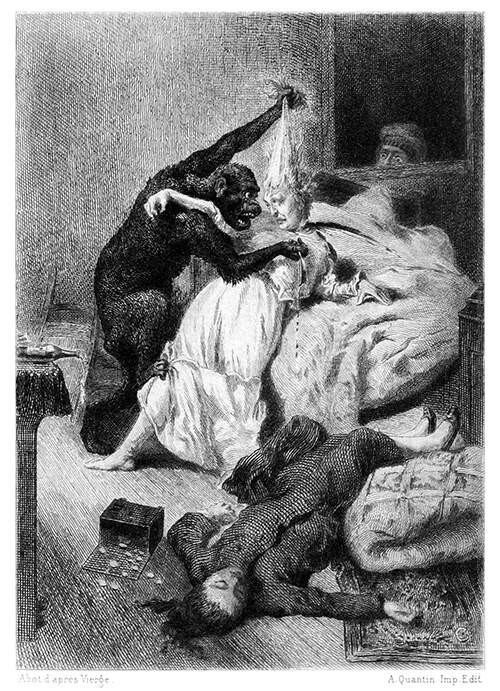

Reflecting upon Eliot’s argument today, it is impossible to ignore the arrant snobbery of his assertion that there are subjects which are simply unfit to be the stuff of true literature. Whatever else Poe might be guilty of, it seems that in Eliot’s eyes his worst crime was to write stories featuring flying machines, life beyond death, or a murderous orang-utan. And yet it was Poe’s daring experimentation with such outré concepts which resulted in him becoming one of the key figures in the history of popular literature. As the author who reinvented Gothic fiction for an American audience, he utterly revitalized this literary form just when it was growing stale in Europe. With works like ‘The Black Cat’ (1843), ‘The Premature Burial’ (1844), ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ (1842) and ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839), Poe came closer than any writer ever has to perfecting the tale of terror, and inaugurated the subgenre of Weird fiction best exemplified by the crawling cosmic chaos of his most devoted disciple, H.P. Lovecraft. He also excelled at crafting unforgettable shock moments, a technique imitated by everyone from David Cronenberg to the writers of American Horror Story (2011-).

The shadow of Poe’s influence extends far beyond the realm of horror. If he has been compared to that other master exploiter of universal human fears and dreads, Alfred Hitchcock, Poe was also the Steven Spielberg of his day, a storyteller exceptionally alert to the potential of new trends and fashionable ideas. Arthur Conan Doyle gratefully admitted that the Sherlock Holmes stories were essentially Poe’s tales of ratiocination with the cerebral element toned down and bolstered by a healthy dose of sensational action. The police procedural subgenre, found everywhere from the Wallander (2005-13) and Inspector Morse novels (1975-99) to Bones (2005-17) to the CSI franchise (2000-15), was as much his invention as that of Charles Dickens or Wilkie Collins. The fantastic machines and globetrotting extravaganzas of Jules Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires (1863-1905) derived from the Frenchman’s admiration for Poe’s vividly convincing accounts of balloon journeys and moon flights, and H.G. Wells’ tales of time travel to distant future ages also have clear prototypes in Poe’s writing. Indeed, the entire field of speculative fiction would be unimaginable without his contribution.

While the richness of Poe’s creative legacy has rarely been underestimated, his theories concerning the value of popular literature are often overlooked. Just as the traditional forms of mass media are now being rapidly displaced by blogs, Facebook and Netflix, in Poe’s age there was a vast proliferation of new sources of information and entertainment: newspapers and journals could be printed in massive quantities, the public appetite for stories soared, and Poe astutely realized that this would have a lasting impact on literature itself. In his critical writings, he contends that these developments have sounded the death knell for the multi-volume novel and the long poem, and argues that much more economical, elegant and innovative varieties of literature will take their place. In his essay ‘The Philosophy of Composition’ (1846), for instance, he insists that a modern poem or tale ought to be based upon the principle of ‘unity of effect,’ the notion that it should be capable of being read in one sitting and contain only those elements required to create a single indelible impression.

For Poe, the change reshaping the literary landscape in his lifetime was an enormous opportunity. Here was a chance to jettison the deliberate obscurantism beloved of bloated hacks, refound poetry and fiction upon sensible artistic precepts, and allow for the creation of a literature much closer to authentic human thought and feeling. His devastating attacks on the turgid, derivative poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and the ponderous, formulaic novels of James Fenimore Cooper (in these articles, some of the funniest pieces of literary criticism ever written, he charged the former with committing “one of the most palpable plagiarisms ever perpetrated” and the latter with concocting “a flashy succession of ill-conceived and miserably executed literary productions, each more silly than its predecessor”) (Edgar Allan Poe, Essays and Reviews, ed. G.R. Thompson (New York: Library of America, 1984), p 765, 473) are less the malicious posturing of an envious younger writer and more a passionate demand for a democratic form of literature characterised by originality, beauty and excitement. Poe’s most radical opinion was that there was no reason why a work of genius could not also be popular. On the contrary, the more skilfully a writer combined their intellect and imagination the more likely the result would be popular, as Daniel Defoe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Dickens had demonstrated.

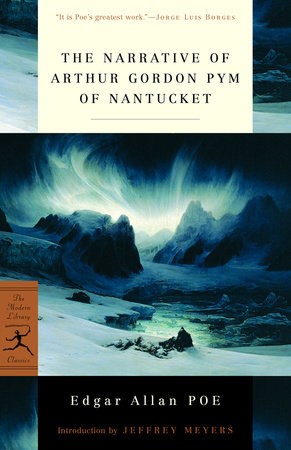

None of Poe’s own works illustrates his theory of what popular fiction could be better than his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). This nautical adventure story begins with all the stock situations (mutiny, storm, shipwreck) characteristic of the genre. Later, as it reaches its closing hallucinatory chapters set within the Antarctic Circle, Poe’s seafaring tale transforms into something altogether more ambitious and impressive:a visionary representation of humanity’s everlasting determination to venture into the unknown. Even though it was ridiculed in its day, this novel, along with Poe’s other Gothic sea stories, almost certainly helped to inspire the allegorical maritime masterpieces of Herman Melville.

Poe’s narrators are perhaps his greatest gift to fiction. Brilliant and eloquent but riddled with obsessive compulsive disorders and aghast at their own propensity for irrational brutality, they remain thoroughly modern figures, and have re-emerged in various guises in the work of luminaries as diverse as Vladimir Nabokov and Stephen King. Comforting though it is to interpret them as the author’s self-portraits, the uneasy truth is that they are us with all of our self-destructive perversity and loathsome cruelty revealed. In the end, Poe imagined nothing more bizarre or grotesque than the world in which we live.

____________________________________________

Edward O’Hare studied for the M.Phil in Popular Literature at Trinity College Dublin and completed his Ph.D on the representation of the Antarctic in Gothic fiction in 2017. A regular contributor to The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, his research has focused on the work of Edgar Allan Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, and the tradition of the Weird Tale. Ed’s interests include British and American horror fiction and film, nineteenth century Gothic science fiction, dystopian literature and anything featuring Vincent Price.