When Anthony Horowitz’s second James Bond book Forever And A Day is released in May 2018 (according to the publicity, a prequel to Casino Royale), it will be around the fiftieth official Bond book (though it depends how you count them) and that doesn’t include the ten or so Young Bond books or the three Moneypenny Diaries, which are also official. During this period since the first Bond film, Dr No, was released with Sean Connery as Bond in 1962 (though it wasn’t the first screen version – that was a short TV version, released in the US in 1954 of Casino Royale starring Barry Nelson as ‘Jimmy Bond’, CIA agent, with Peter Lorre as Le Chiffre), there have been twenty-four official Bond films from Eon. Also the Royal Mint has just launched a new set of 10 pence coins, with twenty-six designs—one for each letter of the alphabet—which, according to Edward Biddulph’s James Bond Memes website, are ‘celebrating aspects of life that are “quintessentially British”, and James Bond is among them, representing the letter B’ (figure 1):

‘The coin, like the various postage stamp issues that feature Bond and Bond’s appearance in the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, provides another indication of how deeply embedded Ian Fleming’s creation is in the cultural environment. Regardless of the pitfalls of defining what is quintessentially British, I’m rather thrilled that James Bond has been celebrated on the face of a coin. It is testament to the character’s continued currency (if you excuse the pun) in popular culture, and is curiously appropriate, given Ian Fleming’s interest in coinage (as reflected, for example in Live and Let Die). Indeed, it’s only a matter of time before Ian Fleming himself appears on a £10 note’ (jamesbondmemes.com, 2018).

Figure 1: ‘B’ Bond (photo: The Westminster Collection)

So it’s timely to reassess Bond and his place in popular literature and culture.

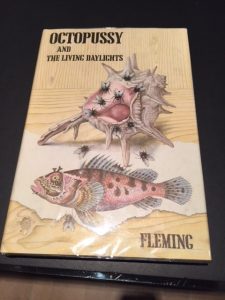

It’s a cliché to compare the popularity of Sherlock Holmes and Bond, but both are considered to be real individuals by millions of people, and each has its own industry, following the demise of their original creators, respectively Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Ian Fleming. Films, TV, pastiches, comics, games, memorabilia, toys….the list is endless. Of course Holmes has had a forty year head start: the last Holmes story was written by Conan Doyle (who died in 1930) in 1927, and the last Fleming book, Octopussy (figure 2), was published posthumously in 1966. Both characters have totally captured the public’s imagination and are included in our modern cultural zeitgeist, though for each of us the positioning is totally different. In the case of Holmes, thousands and thousands of books have been written and films made out of copyright—spoofs, pastiches, commentary, criticism, film and TV—and Bond is going that way too. Apparently the copyright for Bond has lapsed in Canada, so could the floodgates be about to open? So far, just a collection of short stories, Licence Expired, and two novellas, Bond Unknown (figure 3), have been published, though there have been lots of other unofficial under-the-radar books and stories published (and not only in Canada either). One literary trick to avoid breach of copyright has been to have Fleming himself as the main spy protagonist of a number of pastiche novels. But without a doubt, both Holmes and Bond are at the pinnacles of their respective detective and spy pantheons, their immortality seemingly assured forever. (I like Donald Stanley’s short spoof Holmes Meets 007, which originally appeared in The San Francisco Examiner in November 1964 and was reissued in 1967 as a limited edition, in which M is unmasked as Moriarty and Watson as Blofeld!).

Figure 2

Figure 3

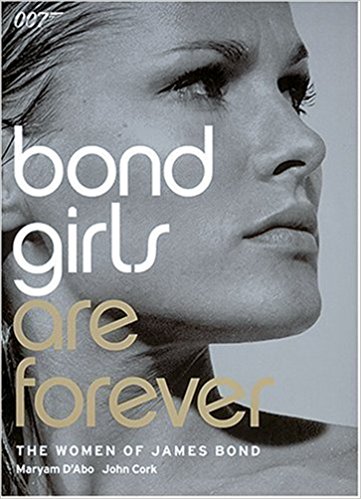

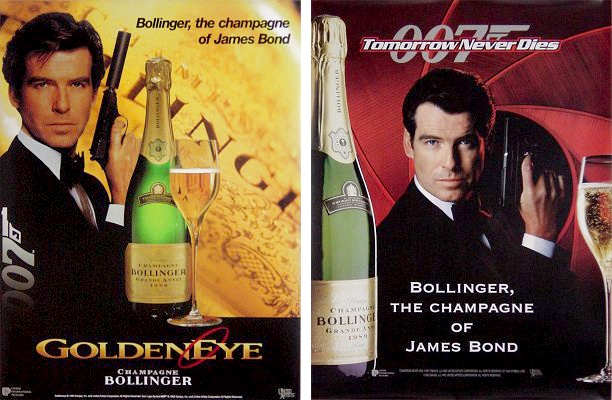

In 1953, Fleming launched Bond onto an unsuspecting public with Casino Royale, the first, the best and still the most iconic Bond book. Without it nothing else would have mattered: the spare, journalistic prose; the casino theme that permeates the books, continuation books and films; the product placement; the Bond Girls (see Bond Girls Are Forever [2003] by Maryam d’Abo and John Cork, with a picture of Ursula Andress on the DJ [figure 4]); the martinis and champagne (Bond is primarily a champagne drinker [me too]). The books and films have always included handsome men and beautiful women. However, over the years there’s been an evolution of the apparent misogyny in the books and films, so that hopefully now it’s starting to resonate with such movements as, for example, the #MeToo campaign. Remember M (Judi Dench) calling Bond (Pierce Brosnan) ‘a sexist misogynistic dinosaur’ in Goldeneye (1995)…? Although the casual sex and double entendres as portrayed in the books and early films may not be acceptable these days, they were a mirror of their times, and the Bond films have always had strong women (these days typified by Naomie Harris, but previously, for example, by Dench, Ursula Andress, Honor Blackman, Famke Janssen, Halle Berry, Michelle Yeoh and Caroline Munro, to name but a few…). Bond drinks martinis/vespers in seven books and short stories and six films, whereas he drinks champagne in seven books etc. and nineteen films, according to David Leigh’s book The Complete Guide to the Drinks of James Bond. Bond’s overall favourite is Bollinger in two books and at least eleven films (AbFab’s ‘Bolly’). Other Bond choices seem to be Taittinger, Dom Perignon, Veuve Clicquot, Krug and Pommery).

Figure 4

Figure 5

By 1964, when Fleming died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six, undoubtedly brought on by too much ‘good living’, he had written a total of twelve novels and two short story collections, so the remaining thirty-six or so ‘continuation’ books have all been written by different authors, culminating with Horowitz, but along the way including Kingsley Amis, John Pearson, John Gardner, Christopher Wood, Raymond Benson, Sebastian Faulks, Jeffrey Deaver and William Boyd.

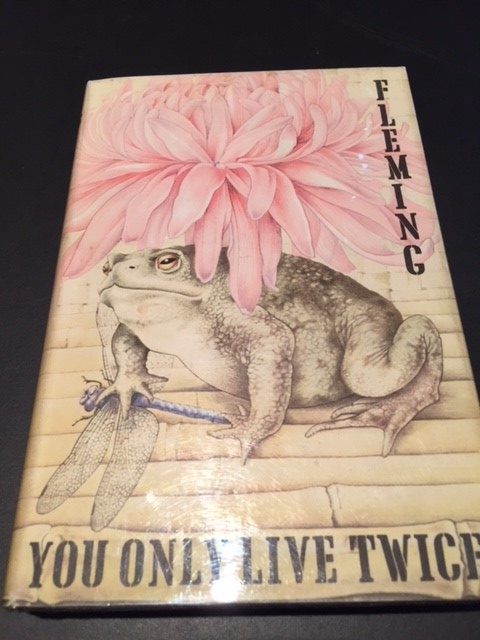

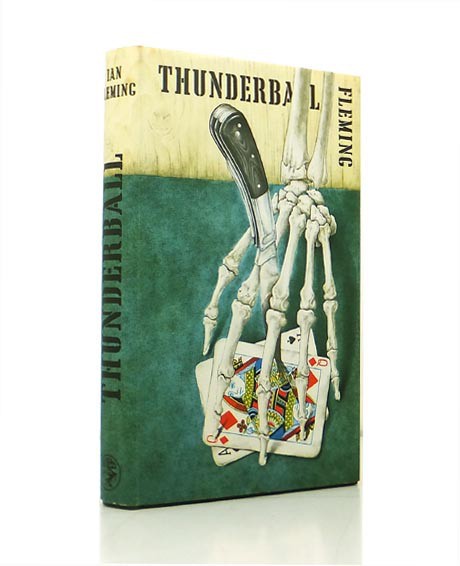

Richard Chopping’s outstanding covers became synonymous with the series, starting with From Russia With Love. My favourite Chopping DJ is from You Only Live Twice, with the chrysanthemum, toad and dragonfly (figure 6). It’s a pretty good novel too. 2017 was also the 50th anniversary of the film, originally released in 1967. Set in Japan, the most far flung and exotic of the Bond locations of both the books and films, Fleming visited Japan and Tokyo in 1959 for his Sunday Times series, later published in book form as Thrilling Cities (1963). I also really like the Thunderball cover from 1961 (figure 7).

Figure 6

Figure 7

But why is Bond so significant? How did Bond manage to tap into the rich vein of our and others’ psyches? Was there a tipping point for Bond? Some event we can identify that lifted Bond out of a relatively pedestrian (at the time) literary Spyland?

First, we all have to have icons (Neil Gaiman makes a compelling case for this in his novel American Gods [2001]). Moreover, with the current cult for celebrity (including ‘five minutes of fame’), characters like Holmes and Bond fulfil such criteria (of course other modern cults from Doctor Who to Star Wars to the Marvel/DC films also qualify, but they have not originated from a strictly literary base [emerging largely from graphic novels and comics], though currently they certainly seem to have the same sort of staying power). Maybe Leslie Charteris’s The Saint and John Buchan’s Richard Hannay, the hero of The Thirty Nine Steps (made into a tremendous early Alfred Hitchcock film) do qualify a bit, because of their respective film and TV iterations, but I submit they’re still not at or even near the top, and their continued popularity is moot. (Robert J Harris—not the same as the author of Conclave and Munich—has just revived Hannay in a 2017 pastiche, The Thirty-One Kings: Richard Hannay Returns). Second, in literary terms, things like detective stories (Holmes) and spy stories (Bond) fall into different genres, though I’m of the opinion that spy stories are the ‘children’ of detective stories.

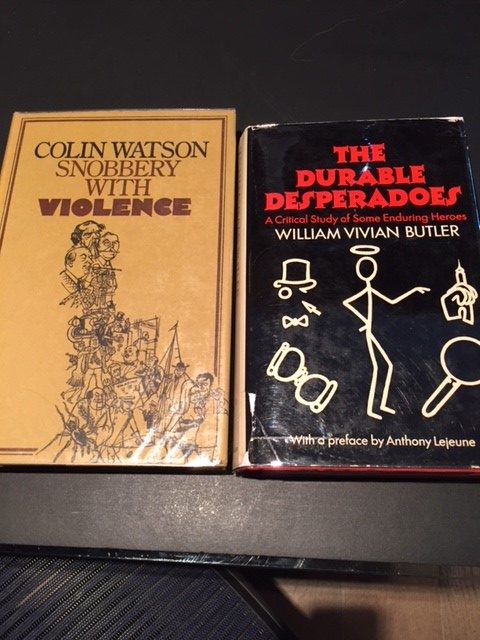

Many Bond aficionados play the game about which literary or real-life person was the inspiration for Bond. I’m not keen on the idea of Bond being modelled on any one predecessor. Books like Richard Usborne’s Clubland Heroes (1953), Colin Watson’s Snobbery With Violence (1971) and William Vivian Butlers’s The Durable Desperadoes (1973) (figure 8) in my view support the genre thesis, and I think Mike Ripley’s recent book, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2017), which reviews the British ‘thrillers’ from Casino Royale (1953) to Jack Higgins’ The Eagle Has Landed (1975) also makes the same point. So Leslie Charteris’s The Saint, Jean Bruce’s OSS117, and Dennis Wheatley’s Gregory Sallust (my favourite) are all role models because they are all in the ‘spy’ genre, as are others. For example, Monet and Renoir (and other Impressionists) painted side by side many of the same views/scenes. It’s accepted that artists (and for that matter musicians) regularly share each other’s ideas/concepts. In their case plagiarism seems to be the highest form of flattery. All of them are trying to produce something unique, but in the relevant genre or subset of the genre. With literature it’s the same: historical, science fiction, detective, westerns, etc, all share their own common background, as do spy stories. So of course, Fleming plagiarised, but his particular iteration was the one that really succeeded and captured the imagination at the level we’ve come to know and expect. So in the spy pantheon, Bond is at the top and his influences are irrelevant, except that they led him to the pinnacle….

Figure 8

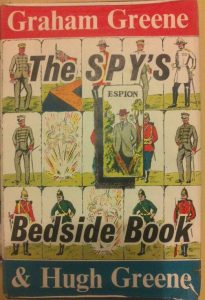

Given that the genre is the genre, where did Bond begin? Yes, Le Queux, Oppenheim, Maugham, Buchan, even Kipling (just look at the authors in The Spy’s Bedside Book (1957) edited by Graham and Hugh Greene [figure 9]), but for me Eric Ambler encapsulates this in his sixteen page analysis of the start of the spy genre in the Introduction to the To Catch A Spy (1964) anthology. He writes: ‘The sudden emergence, in the 19th century, of the detective story has been satisfactorily accounted for […] Clearly there could be no detective stories until there were detectives […] The belated arrival of the spy story is less easy to understand […] Prostitution may, as we are told, be the oldest profession, but that of the spy cannot be much younger […] And yet, it is impossible to find any spy story of note written before the 20th century’.

Figure 9

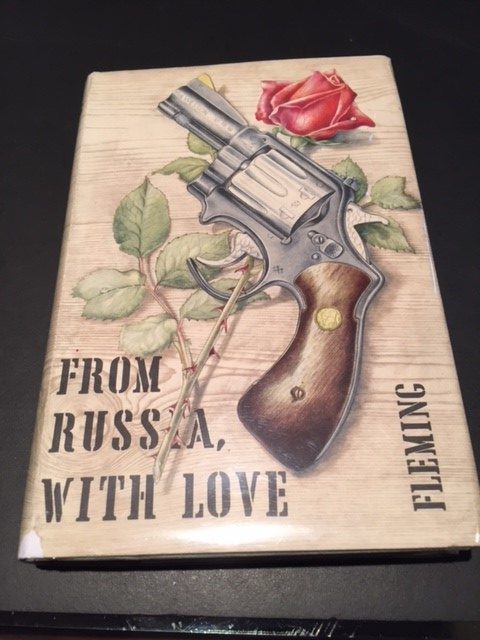

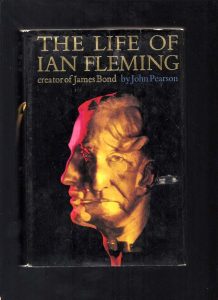

So given that Bond is at the pinnacle, can we pinpoint the tipping point? I believe we can. Even though, in the UK, Bond was increasing in popularity, in the US he wasn’t, and you need the US to succeed. In the March 1961 issue of Life Magazine, a list of President John F Kennedy’s Top Ten books was published, with From Russia With Love (1957) (figure 10) coming in ninth place. After the endorsement of JFK (another modern icon), by the end of 1961 Fleming had become the biggest selling thriller writer in the US. Various stories from John Pearson’s The Life of Ian Fleming (1966) (figure 11, which also has a nice DJ designed by artist and author Jan Pienkowski, of Haunted House pop-up book fame. Pearson also wrote James Bond: The Authorised Biography of 007 [1973]) and Andrew Lycett’s Ian Fleming (1995), and a good article from Tom Cull’s Artistic Licence Renewed site (literary007.com) ‘Ian Fleming and JFK… 50 Years Later’ (28 November 2013) explain that JFK met Fleming in 1960 while JFK was running for President. Jackie Kennedy also introduced Allen Welsh Dulles, former Director of Central Intelligence and Head of the CIA, to From Russia With Love, and was quoted as saying: ‘Here is a book you should have, Mr Director’. By October 1961, the actor Henry Brandon was telling Fleming that ‘the entire Kennedy family is crazy about James Bond’. When the film of Dr No (1962) was released, JFK arranged a private screening at the White House. It is said that the film of From Russia With Love (1963) was the last film JFK watched before going to Dallas. The night before the assassination, both JFK and Lee Harvey Oswald were said to be reading Bond novels: the FBI found Live And Let Die (1954) and The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) amongst Oswald’s possessions. Fleming sent inscribed copies of the novels to JFK and continued to send them to the family after JFK’s murder. In 1964 Bobby Kennedy thanked Fleming for the signed copy of You Only Live Twice (1964) on a black-edged card: ‘I wish someone else could read it also’.

Figure 10

Figure 11

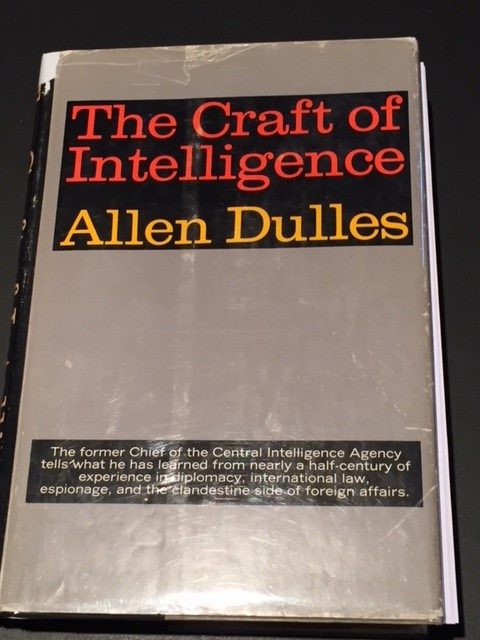

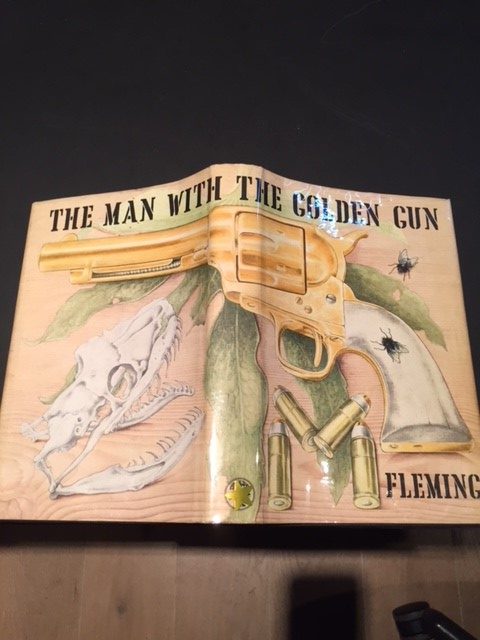

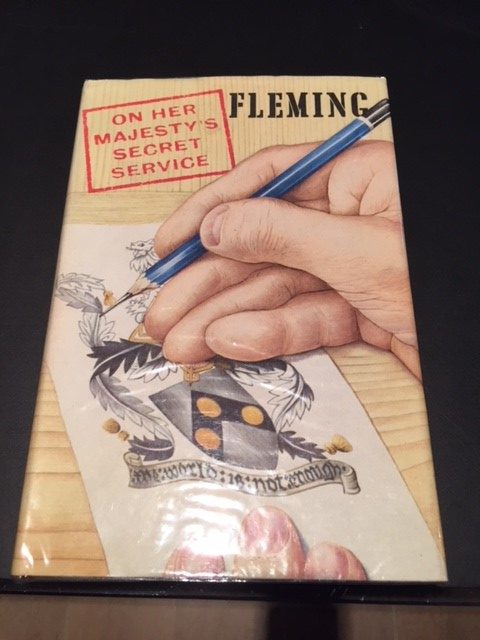

Interestingly, there are other JFK/Fleming/Dulles links. Dulles was a member of the Warren Commission (The Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, established by President Lyndon B. Johnson on 29 November 1963 to investigate the assassination. The Commission took its unofficial name from its chairman, Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court). Dulles had written The Craft of Intelligence (1963) (figure 12) about the CIA and his career, a book which Bond is reading in the last chapter of The Man With The Golden Gun (1965), (figure 13: the only Fleming ‘wrap-around’ DJ), and Dulles talks about enjoying reading On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963) on page 199 (figure 14).

Figure 12

Figure 13

So JFK was the most famous and influential Bond fan of all time. Without him, would Bond have stormed the US and become the icon we know and love today? Possibly not.

But in many ways, for me, looking forward is the important thing in this spy genre. So whilst I accept that Bond is derivative (albeit the acme of perfection), that does not affect his popularity. I believe he was the watershed between the old guard and the new. So would we have had the anti-Bonds—Len Deighton (‘the poet of the spy story’, according to the Sunday Times), John Le Carré (ranked number twenty-two by The Times in its list of ‘The Fifty Greatest British Writers Since 1945’), John Gardner’s Boysie Oakes, etc.—without Bond, and then books like Mick Herron’s Slow Horses (his latest book in the “Slough House” series, London Rules, has just been published), that is the question?!

Figure 14

Bio:

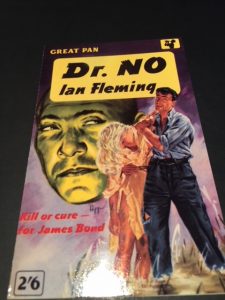

This month’s blogger is Robert ‘Raki’ Rakison. He is a lifelong aficionado of the spy genre, particularly Ian Fleming and James Bond. ‘I was brought up on Buchan, Rider Haggard, Conan Doyle, Kipling, Tolkien and Dumas. I then became a voracious reader of fiction like Faulkner, Hemingway, Huxley, Orwell, Graves and Waugh, as well as SF and fantasy. At ten I read From Russia With Love (figure 10) probably my Dad’s copy (I loved the Richard Chopping cover), and thought it was fantastic, and then read Dr No a bit later as a paperback (with a great Peff cover) (figure 15). When Honeychile Ryder walked out of the sea, that was it! I was totally hooked on Bond’.

Figure 15