York City Archives, Gray GRF/4/3 J.16

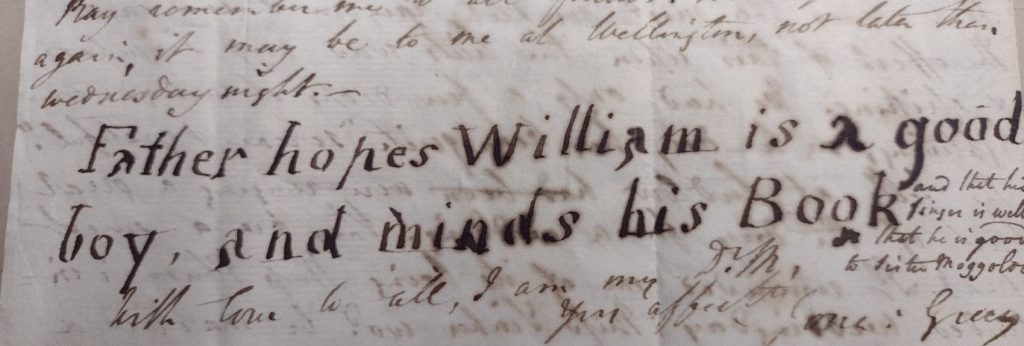

In 1809, Jonathan Gray of Gray’s Inn in York signed off a letter to his wife, Mary with these words to his two year old son: ‘Father hopes William is a good boy, and minds his Book’. This sentence is clearly printed in large block letters and is followed by a few words in his usual hand. In order to write this message to his young son, Jonathan has had to change the nib of his pen or quill, either by cutting a new nib or by changing his writing implement. He has carefully selected short words, that might be decipherable to a young reader, with the more challenging sentiments on his health and his behaviour towards his sister being intended to be read to him by his mother. Given that William was only two years old, I suspect that this note from his father was designed to be read to him, while the reader pointed to the words.

Whilst schoolmasters and tutors taught children the basics of communication by letter in the eighteenth century, the cultural art of letter-writing was learned through a composite of methods the most important of which was sending and receiving letters from family members.[1] It was through writing (and receiving comment upon) letters, and reading ‘good’ letters that children learned to communicate in ways that were appropriate to their gender and social status. The familiar style of letter writing, popularised in the second half of the eighteenth century, placed value upon an informal conversational style that was nevertheless highly formulaic. By looking at the letters to William Gray during his youth, we can see some of these writing conventions being taught. So important was letter-writing in the eighteenth-century, that teaching these skills was a collaborative endeavour between family members. Writing letters was a way for extended family to contribute to the education of the next generation, particularly as they were more likely to be separated from children than their parents.

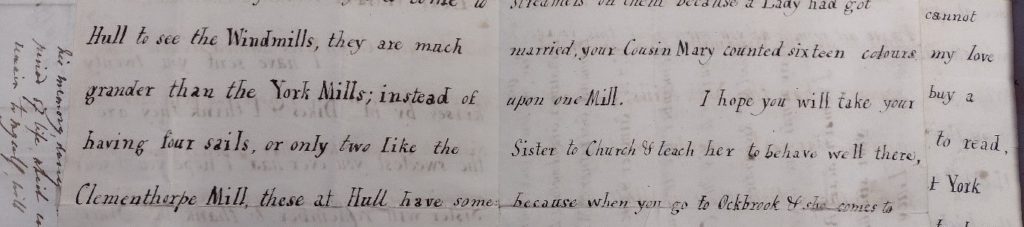

The year after receiving the note from his father, William received a letter from his Aunt Lucy. Lucy was 23 years old and unmarried when she began corresponding with three-year old William. Her writing is much smaller than that in his father’s letter, but still clearly printed, with large spaces between the lines, making it easy to read. Some of the content is didactic, for example she told him about a local miller that works on Sundays to emphasise that Sunday should be a day of rest. Most of the content, however, appears to be tailored to William’s interests. Windmills feature heavily in her letters and, by the age of four, ships have clearly been added to his list of interests. Hidden in Aunt Lucy’s stories of her travels, however, are instructions on letter-writing conventions. In 1811, when William was four, she instructed him ‘I should be glad to have a Letter from you to hear about your journey to Easingwold’.

York City Archives, Gray GRF/4/4/1 M3(c)

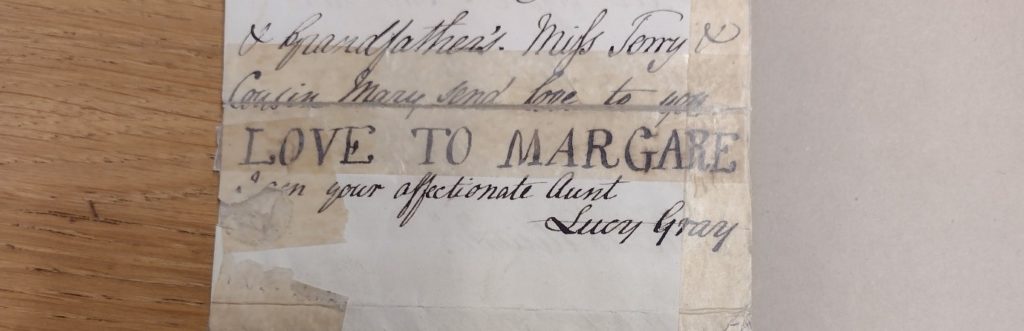

William was clearly a diligent student. In 1812, aged just five, his aunt wrote to him in round hand. She acknowledged his progress at the outset of the letter, writing ‘As you are now in round hand, I need not take the trouble of printing Letters to you again’, though she acknowledged that she will still print letters to his younger sister. Her writing is still large, and carefully spaced to make it easier to read but more closely resembles the handwriting of adult letter writers. On the final page, is a printed message to William’s sister. This letter is quite short, but includes many of the conventions found in adult correspondence. She thanks William for his gifts to her and anticipates receiving another letter from him in a parcel sent by his mother. This reference to the temporalities of letter-writing encourages William to think about opportunities to send letters as they are presented. Many of the letters that we have transcribed already as part of this project are written in response to such an opportunity – a visit from a friend who is returning home, or the parcelling of goods, saving the recipient the price of postage.

York City Archives, Gray GRF/4/4/1 M3(d)

Lucy’s role in educating William might be an important part of her own education. As a young woman of marriageable age, writing appropriately to William was potentially part of her training for marriage and parenthood, as was undoubtedly envisioned for her by the rest of the family. Yet Aunt Lucy also a particular connection to her nieces and nephews that was developed during regular visits, the sending of gifts and, presumably, letters like these. When Lucy died suddenly in 1813, William’s father Jonathan sought out a good likeness of her to hang on the Nursery walls.[2]

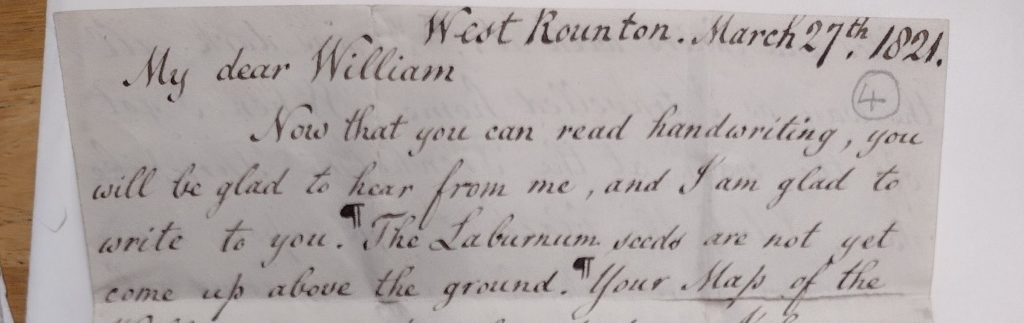

The final letter in this bundle falls slightly outside the scope of this project, being written in 1821 by William’s father when William was a young man of 14. Again, it marks a moment of William’s letter-writing literacy, starting ‘Now that you can read handwriting, you will be glad to hear from me, and I’m glad to write to you.’ This letter rather beautifully combines instruction with genuine affection, recognising Williams’ youth with funny stories about the sights he has seen whilst also expecting him to engage with family news and the health of acquaintances like an adult. Jonathan includes tales of frightening the maids by coming home late, of carrying his black trunk on his shoulders all the way home from the Turnpike Bar, and promises to ‘make a tale about the Minster, and the Wild Beasts, and the Wooden Horse, and the Ship, and the Beef-eaters, and the dead Peacock, and the Bar-Walls, and all the good people of York and it’s good things’.

York City Archives Gray GRF/4/4/3 2

These exciting snippets of life in York and promises for William’s next visit, are sandwiched between examples of ‘good’ letter-writing practice such as news of Mr Shepherd’s improving health, and messages for Mama, and Aunt Jane. Jonathan even used a little symbol to help William identify a change in subject, writing ‘Wherever there is a black P, it means that a new thing begins there to be written about.

These four letters neatly encapsulate William’s letter-writing literacy, and the way in which it developed. He undoubtedly learned to read, write and form letters with his tutor, as the address on the letters suggests that he was not sent away for his schooling. Perhaps, as the family lived in York, he received tuition at a day school. Yet his socialisation into the world of letter-writing was provided by letters such as these to his aunt and his father. It is interesting to speculate on why these four letters, out of what was clearly a much greater correspondence, were kept and found their way into the York City Archives. Is it because they chart his growth and development as a letter-writer? We will be keeping an eye out for similar patterns in other children’s correspondence that we analyse during this project.

[1] Susan Whyman, The Pen and the People: English Letter-Writers 1660-1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Willemijn Ruberg and Maria C. Sherwood-Smith, Conventional Correspondence: Epistolary Culture of the Dutch Elite, 1770-1850’ (Leiden: Brill, 2009)

[2] Almira Vickers Gray, Papers and Diaries of a York family 1764-1839 by Mrs Edwin Gray (London: Sheldon Press, 1927), 125.