‘I think your eyes must be better’, Mary Bostock wrote to Mary Huddleston in May 1810, ‘for I am sure you write as well as ever’. [1] Bostock understood the quality of Huddleston’s handwriting to be a direct indication of her correspondent’s health: she was aware of the subtle changes in how her relative formed her words, and saw this as evidence either of an improvement or deterioration of Huddleston’s eyesight. The visible evidence of the letter-writing process: both the quality of the handwriting, the forming and shaping of characters, and the organising of coherent sentences, could be said to belie the health of eighteenth-century letter-writers. Worsening eyesight could lead to degenerating script; pain or tremors in the hand could produce shaky or illegible scrawls, and indeed, a confused or hurried mind could in turn produce writing that was confused, rushed, or incoherently set out. News of health and sickness was transmitted not only in the content of familiar letters, but also in their materiality: in evidence of altered handwriting or composition that immediately and visibly transmitted details of the author’s health and state of mind.

Deborah E Thorpe’s interdisciplinary work in this space has examined how handwriting could indicate the health of a writer in a range of contexts spanning from the visible tremor in the script of thirteenth-century scribe ‘the Tremulous Hand of Worcester’, to evidence of neurological illness in John Ruskin’s letters, to the ‘disordered handwriting’ of patients at an early twentieth century German psychiatric hospital.[2] In this short blog post I’m not attempting to retrospectively diagnose any of our eighteenth-century letter writers, but to consider the broad range of ways in which quality of hand could be thought to convey relative health, and examples where an increasingly shaky or erratic hand directly maps onto a health condition discussed in the content of a letter itself.

One of the most visible indications of a debilitating health condition which affected letter-writing was the changing of hands that denoted the use of a scribe. Elizabeth Elstob was afflicted by chronic and painful problems with her right hand, which often prevented her writing, and which prompted her to employ the schoolgirls she was teaching as scribes. In one letter (dated 1750) she informed her friend George Ballard:

my chief complaint is weakness, & the dread I am in of Loseing the use of my right Hand by a contraction in the sinew which Disables me from writing & obliges me to give my sweet Lady’s the trouble of writing for me.[3]

Elstob was a teacher and noted scholar: she had, throughout her life, relied on her writing for both her career and for leisure purposes. Ballard, who often collaborated with her on antiquarian projects, would have an intimate understanding of the very real ‘dread’ that Elstob would feel at the thought of losing the use of her hand.

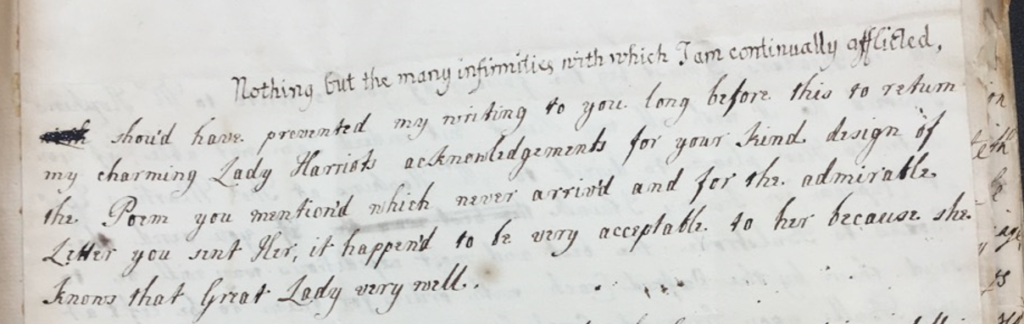

A letter written two years later, dated November 1752, immediately reveals that Elstob’s problems were persisting. It begins in her handwriting, but after only a single sentence, Elstob’s hand ostensibly became too painful or uncooperative, and someone else, presumably one of Elstob’s aforementioned pupils, takes up the pen and writes the remainder of the letter.

Fig. 1. Bodleian MS Ballard 43 96, Elizabeth Elstob to George Ballard, 14 Nov 1752

Elstob barely makes it to the end of the first line, writing only ‘Nothing but the many infirmities with which I am continually afflicted’ while a different hand continues the sentence ‘shou’d have prevented my writing to you long before this’.[4] In this letter Elstob’s clear and cheerfully round handwriting has been marked out with clear determination and an uncharacteristically uneven pressure on her pen: it is not hard to imagine the effort it took to overcome her debilitating condition to get those first eleven words onto the page.

Samuel Wesley, in the decline of life, also engaged others to write letters for him. One such letter is dated August 1734, when Wesley was aged 71, and indeed, was just a few months away from his death. The entire letter is in a different hand, but Samuel’s signature appears at the bottom of the page: it is an extremely shaky and weak hand, showing possible signs of a tremor.

In the final sentence of the letter itself, Wesley, who was presumably dictating, made reference to his failing health: ‘We are all well, except him, who may best be spard, who is something better than he has been, & is with Blessing to you & Company, your Lov: Fa:’.[5] Wesley, writing to a son who would be familiar with his father’s handwriting, perhaps references his failing health before he signs his name to pre-empt the shakiness of the signature, and also to explain why the rest of the letter does not appear in his own hand. This is perhaps also why Elstob was so desperate to write the first line of her letter herself, and also why she set forth, from the outset, her apologies for how her poor health had affected her ability to write. When letters were exchanged between those who intimately knew each other’s hands and health, such details – a visible tremor, a noticeably varied pressure on the pen, or the inability to write at all without a scribe – could reveal far more about an individual’s state of body and mind than the content of the letter alone. When viewed in the context of a run of letters, and when certain health conditions were discussed and manifested themselves in the form of ink, shared understandings of improvement and deterioration of health could be created.

Accordingly when Frances Jerningham wrote to her daughter Charlotte in June 1786, she began the letter by writing ‘I think you will be glad to see my Hand-writing again & therefore I make use of my returning good Health to Converse with my poor Little Girl’.[6] The presence of Charlotte’s handwriting was an immediate and visible means of communicating details about Frances’ health: after a period of absence, filled by letters written by Charlotte’s Father only, the return of Frances’ familiar hand signalled the return to health. Charlotte herself wrote a letter later that summer which ended with the words:

I hope you will excuse this foolish letter, but I am surrounded by my Companions who make such a noise that my pen scribbles on without asking any council of my head. It is impossible to write to day.[7]

Charlotte recognised that her family would notice any changes in the quality and coherence of her writing, offering an explanation for why her environment was making her mind and by extension her writing appear confused. When family and close friends exchanged letters, alterations to the appearance and clarity of writing would be immediately visible indications of wellbeing and state of mind. When sent between those who had intimate knowledge of each other’s constitutions and ‘normal’ writing, such details could produce a nuanced understanding of health that was perhaps only visible to writer and recipient. While Samuel Wesley’s signature is visibly shaky to a modern reader, and the pressure Elstob applied to her pen later in life appears noticeably more uneven, there may well be further irregularities and clues about their respective health that were apparent to those who knew them well, but are not discernible to us today. Letters, in both their content and their material features, were manifestations of the wellbeing of their writers, creating shared understandings of health, improvement and deterioration that were in some ways immediately visible, but in others perhaps only perceptible to those who knew them intimately.

[1] Cambridgeshire Archives, K488/C1/MHb/29, Mary Bostock, 29 May 1810.

[2] DE Thorpe, JE Alty, ‘What type of tremor did the medieval ‘Tremulous Hand of Worcester’ have?’ Brain 138 (2015) 3123-7; DE Thorpe, JE Alty, PA Kempster, ‘Health at the writing desk of John Ruskin: a study of handwriting and illness’, Medical Humanities 46, (2020) 31-45; DE Thorpe, Schiegg M., ‘Historical Analyses of Disordered Handwriting: Perspectives on Early 20th-Century Material From a German Psychiatric Hospital’, Written Communication 34 (2017) 30-53.

[3] Bodleian Library, MS Ballard 43 87-87v, Elizabeth Elstob to George Ballard, 12 April 1750.

[4] Bodleian Library, MS Ballard 43 96, Elizabeth Elstob to George Ballard, 14 November 1752.

[5] John Rylands Research Institute and Library, DDFW1/11, Samuel Wesley To John Wesley, 27 August 1734.

[6] Cadbury Research Library, JER/47, Lady Frances Jerningham to Charlotte Jerningham, 26 June 1786.

[7] Cadbury Research Library, JER/50, Charlotte Jerningham to Edward Jerningham (the younger), 15 August 1786.