Our Undergraduate Research Scholar Louisa Day joined the project team in Summer 2019. The UGRS Scholarship enabled Louisa to undertake research on the theme ‘Beyond Song’. We have collated more than 1700 song settings of Baudelaire’s poetry but what other types of musical adaptations can be found? In this first blog post, Louisa examines a music video and interrogates the relationship between words, music, and image.

Adaptations exist, J. Hillis Miller argues, because ‘we need the ‘same’ stories over and over’ as they are ‘one of the most powerful…of ways to assert the basic ideology of our culture’. [1] He claims that they exploit the innate human desire to repeat, replicate and adapt already published works. Charles Baudelaire is the prime candidate for this assessment. His works have been translated into multiple genres (rock, pop, opera etc.), from the nineteenth century until the present day. Repetition and replication take a whole new meaning when an artwork involves several layers of adaptation, particularly when a poem is set to song and associated with a video. My analysis concentrates on the female-fronted Belgian band EXSANGUE who have produced a narrative music video incorporating the ‘same story’ as found in ‘A Une Malabaraise’. [2] In this blog post, I will interrogate the relationship between the ideologies present in the Les Fleurs Du Mal poem and Exsangue’s music video. Are the narrative choices presented in the video in line with the basic ideology of today’s culture? Or is it simply an outdated poem distastefully revived by Exsangue?

Examining Baudelaire’s poem in isolation, there are three themes that link it to Exsangue’s music video. Firstly, the sexualisation of the female body, immerses the reader into the description of the Malabar woman from the outset: ‘Tes pieds sont aussi fins que tes mains, et ta hanche/ Est large à faire envie à la plus belle blanche ;’(l.1-2) [‘your feet are as slender as your hands and your hip/ is broad’]. Initial consideration of this woman favours her physical attributes over her personality traits. Objectification occurs immediately: her body meets the idyllic and unrealistic requirements of a curvaceous woman. This sensual description continues as ‘À l’artiste pensif ton corps est doux et cher;’ (l.3) [‘to the pensive artist your body’s sweet and dear’]. Her body is a commodity, a beautiful vision that can be exploited to gratify others. Baudelaire also interweaves more subtle sexual connotations, for example, the ‘evening’, the ‘scarlet’ colour, and the stretching body (l.13-14).

Secondly, the poems in Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs Du Mal are not overly narrative. However, through asyndetic listing, a small narrative can be found. The poem recounts the woman’s everyday life on her island (probably Mauritius or Réunion – then called Bourbon – that Baudelaire visited) and her aspirations for a better life. For example with ‘Ta tâche est d’allumer la pipe de ton maître,’ (l.6) [‘it is your task to light the pipe of your master’], Baudelaire introduces the concept of duty, after describing her appearance, to her master; she must remain completely subservient to him, even for the most simple of tasks. The poem then moves from the description of the woman’s daily life to her possible dreams of going to France. In the last part of the poem (l.17-28), the poet speculates on what would happen to the Malabar woman if she went to France, suggesting she would remain a prostitute and long for her island.

Finally, whilst it is difficult to pinpoint a narrator, the poet’s voice still enters the poem. Baudelaire makes a social commentary as he questions ‘Pourquoi, l’heureuse enfant, veux-tu voir notre France?’ (l.17) [‘why, happy child, do you wish to see France…?’]. The possessive adjective ‘notre’ as opposed to ‘tu’ might suggest that Baudelaire is making a distinction between the colonisers and the natives of the island even though he may not have been an advocate of colonisation and its repercussions. As Françoise Lionnet argues, Baudelaire might have in fact ‘contributed more to making other cultures and languages visible and present within mainstream French literature’.[3] The poet also warns the Malabar woman to not fall victim to the idealisation of France as there is an emptiness and sense of removal implied in the tone of the question. Baudelaire’s imagery reaches further in his description of the Malabar woman’s likely reality in France. Her life there would involve ‘le corset brutal emprisonnant tes flancs’ (l.24) [a brutal corset imprisoning your flanks] and ‘vendre le parfum de tes charmes étranges’ (l.26) [selling the fragrance of your exotic charms]. Metaphorically, Baudelaire references the sale of her body to men and the services it can provide them rather than of cultural goods, for example.

It is interesting to examine how Exsangue have adapted Baudelaire’s poem into a music video. Arguably, certain themes have become more or less explicit. For example, the emphasis of the colonial aspect of the poem is much less pronounced. In the music video, the female protagonist spends time admiring a photo, potentially of her place of origin. Whilst the location of the video is not specified, this could be harking back to her colonial roots and potentially answering the final part of the poem. Has she found more happiness in her existence back in her home country?

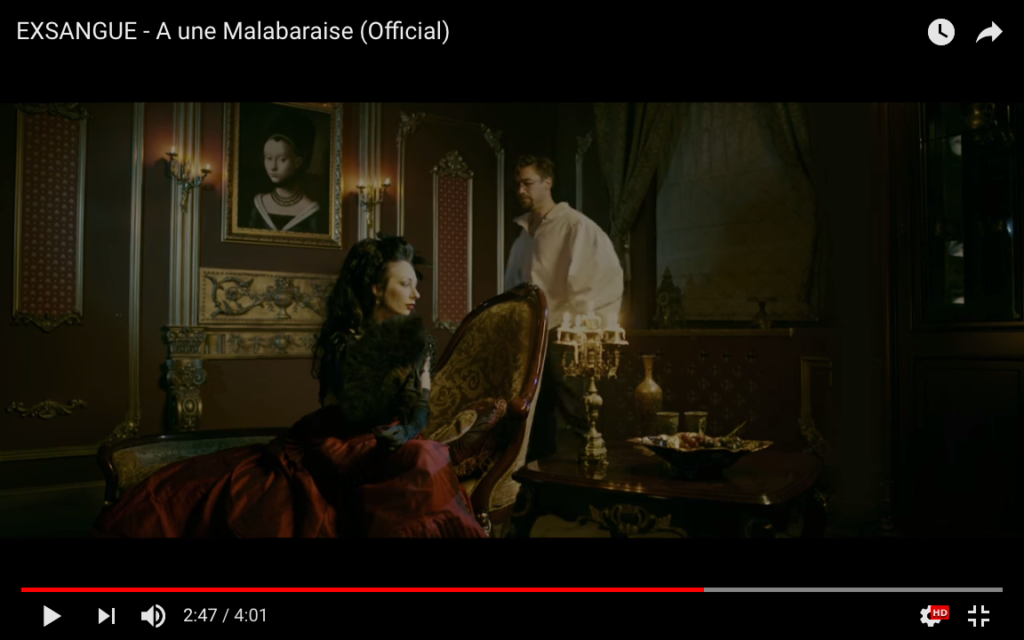

The encounter between the male protagonist and the Malabar woman forms a good proportion of the plot in the music video. In ‘A Une Malabaraise’, it is not clear as to what the male protagonist represents; he could embody the ‘master’, the potential clients of prostitutes (‘les marins’), or the poet himself. Exsangue, however, have extracted a narrative from the interaction of the Malabar woman with other men, using it as the climax to the entire video. The hints that the woman is a prostitute are more explicit. Spatially, there is a distance between the Malabar woman and the man, suggesting a lack of closeness or requited love. In addition, when the man touches her face, she moves away in response. This shows a sense of reluctance from the woman’s perspective. Moreover, when the man feeds her grapes and wine, it seems very forced. The Malabar woman is not a willing participant but in fact she performs a service; she is simply putting on a façade. Finally, the suggestion of sexual intercourse is more explicit in the music video and is interspersed with clips of the band performing music to act as a contrast . For example, the camera flips between Exsnague and the interaction between the female and male protagonists. Naturally, this scene is going to be more suggestive due to the visualisation of ‘A Une Malabaraise’; there is less of a requirement on the reader’s behalf for inference. At the end of the act, the woman is handed money by the man which is confirmation of the Malabar woman’s prostitution.

Whilst there are different emphases placed on themes in ‘A Une Malabaraise’ and Exsangue’s video, the Belgian group have, more or less, held onto the ‘same story’ by remaining faithful to the poem in the song’s lyrics but have presented it in the modernised YouTube music video format. Additionally, it is still within a twenty-first century audience’s reach to understand and relate to the themes addressed. Hence, the success of this adaptation. Furthermore, Hutcheon claims that ‘adaptation as repetition […] is in itself a pleasure’.[4] Whilst music videos naturally are visual and sonic art forms, a poignant and gripping story about an enslaved prostitute has grown out of Baudelaire’s poem. Undoubtedly, one derives a certain satisfaction, in fact thrill, from the story portrayed in the music video as Exsangue have created a beautiful visual narrative out of Baudelaire’s poem.

[1] Joseph Hillis Miller, ‘Narrative’, in Critical Terms for Literary Studies, ed. by Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 66–79 (p. 72).

[2] Charles Baudelaire, Oeuvres Complètes, ed. by Claude Pichois, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, vol. 1 (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), p. 172.

[3] Françoise Lionnet, ‘Reframing Baudelaire: Literary History, Biography, Postcolonial Theory, and Vernacular Languages’, Diacritics, 28 (1998), 63-85 (p.65).

[4] Linda Hutcheon, with Siobhan O’Flynn, A Theory of Adaptation (Abindgon: Routledge, 2013), p.1.