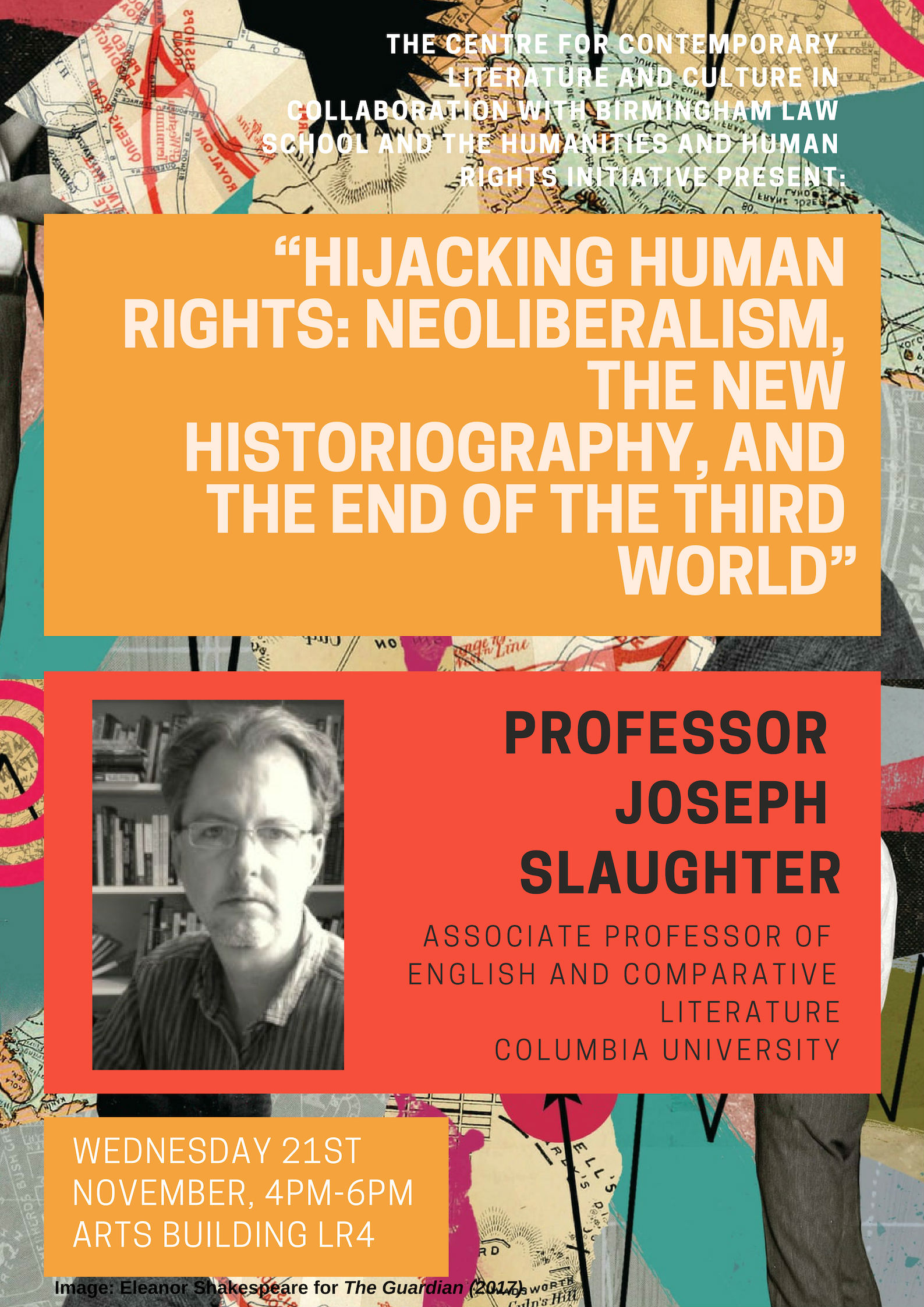

Visiting speaker, Professor Joseph Slaughter, described his lecture as a critique of the new historiography of human rights. He began this critique with an analysis of Milan Kundera’s story ‘The gesture of protest against a violation of human rights’, from his 1991 Immortality, in which the principle character, Brigitte, attempts to buy an expensive bottle of wine during a protest in central Paris against elitist French society. Brigitte, who is perplexed by the ongoing protest that hinders her purchase, develops sympathy for the demonstrators only when she returns to her car and finds a parking fine attached, feeling herself now a part of the common fight for human rights – the universal right to somewhere to park one’s car. Reading from this extract, Slaughter offered this extract as representative of an absurdity of bourgeois individualism within late capitalism. Brigitte’s plight, and her reiteration of her rights, exemplifies how the language of ‘human rights’ has become a benign discourse, a discourse which has lost most – if not all – of its moral force.

This is an effect, he argued, of international neoliberalism, developing most prominently from its relationship and reaction to terrorism in the twenty-first century. He sees a new historiography as attempting to posit a true history of human rights that, through its domineering Western bias, has eclipsed much of its influences from marginalised cultures. Especially exemplary of this is the way in which the new historiographers have proposed the year 1977 as the inaugurating moment of supernational guarantees to human beings of their rights encapsulated, these historiographers propose, by the election of Jimmy Carter in the US and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to human rights organisation Amnesty International. Slaughter explained that this narrative of human rights has had to contend with the necessity of making a problematic distinction between human rights as they are conceptualised in the 1970s and those that are expounded by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. It also denies, he argued, any ongoing popular movements for human rights, focusing overtly on ratified legislation and ignoring mass culture. As an example, Slaughter explained that a 1977-grounded, American-centric story of human rights relegates the worldwide processes of decolonisation to being only nation specific and, therefore, not concerned with human rights as a more generalised or generalisable concept, despite the very terminology of ‘human rights’ appearing amongst varied anti-colonial pamphlets, media articles, and manifestos.

Slaughter then brought our attention to some of the evidential data underpinning a new historiographical depiction of human rights, predominantly the historical mapping of keywords as demonstrative of moments at which they came into ostensibly popular use. He criticises this use of keywords as a limited source of historical knowledge owing partly to the limited selection of sources that were examined by these algorithmic processes, being predominantly from the most mainstream news publications in the US. Slaughter demonstrated how ‘human rights’ as a key term can be found in multiple documents outside of the mainstream media – often in other forms, such as ‘rights of man’ – in the revolutionary literature produced by marginalised groups as far back as the Nineteenth Century. Slaughter shows that, contrary to the neoliberal depiction of isolated decolonisation, subaltern groups around the world were already using language of universal human rights. Algorithms for keyword searches were shown to have Western-bias, but also to demonstrate Anglocentricism in the ways in which they fail to take into account many of the ambiguities found in languages such as French, languages in which many anti-colonialists were writing.

Through this neoliberal historicism, the popularity of human rights in the West becomes a measure of their history as a total, a historical narrowing that erases decolonisation and national self-determination from its records. The corollary that emerges from this narrative falsely suggests, Slaughter informed us, that colonialism had ended by the 1970s on account of the Western project of supernationalising human rights. This was a narrative that, resultantly, re-inscribed the self-determination, that was still resisting the remaining imperialist zones throughout the world at this time, with violent propensities for disrupting the project of human rights. Thus, neoliberalism individualism emerged as a weapon against the self-determination, which was beginning to become reproduced as ‘terrorism’. The genealogy of terrorism, as it is being inflected through neoliberal discourse, shows how it has made a shift from signifying state violence – imparted onto the citizens ruled by violent authoritarianism, often the victims of colonialism – towards a signification of disparate independent aggressions against governments and states – the perpetrators of colonialism; as the trajectories of the sign changed, so did those being constructed as the victims of terrorism. As the individual emerged as the centre for social and ethical responsibility throughout the West in the 1970s and 80s, the role of the state in terroristic activity was replaced by the dis-embedded person whose movement against national rule meant a direct attack on human rights themselves. Thus, Slaughter explained, this procedural switch in the discourse on terrorism saw the delegitimization of national liberation movements and the new incommensurability of human rights and individual dissidence.

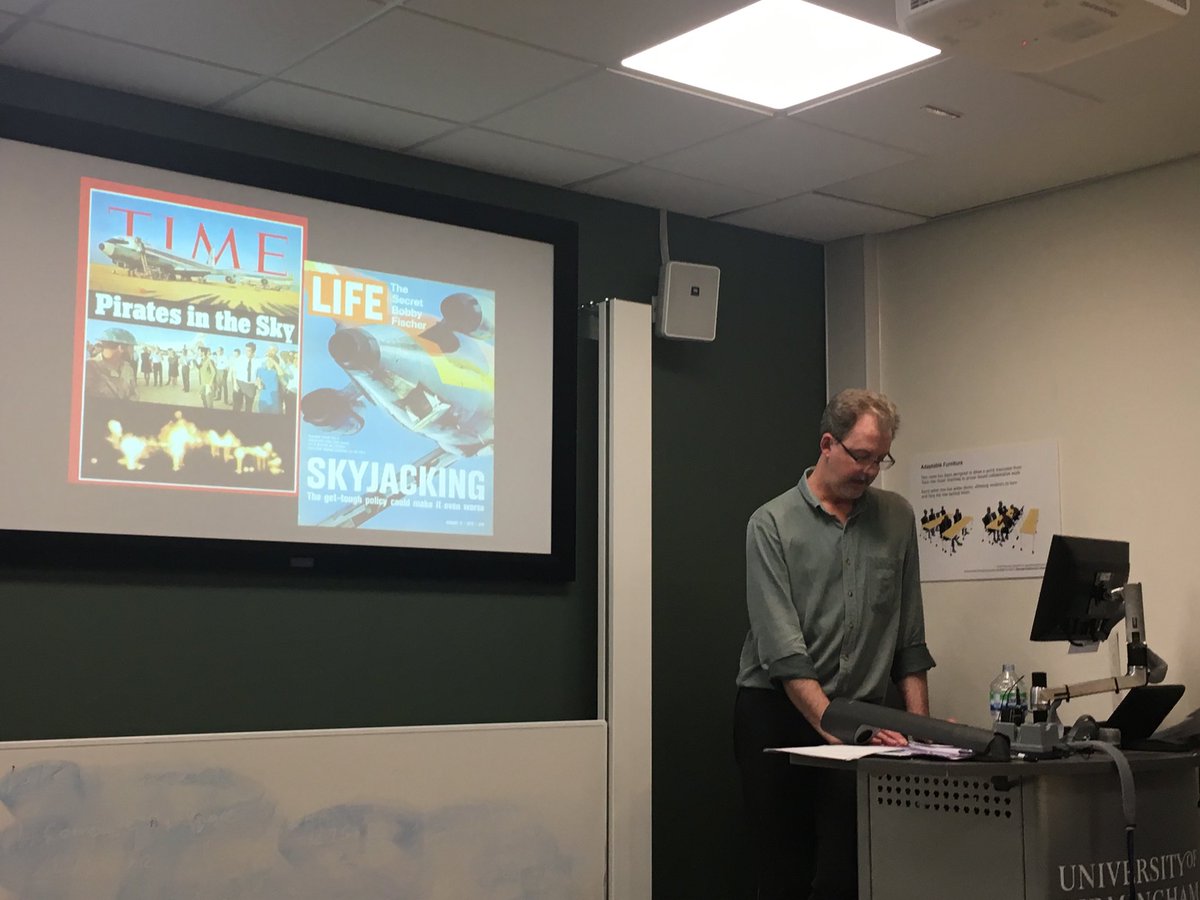

Alongside this, Slaughter argued that this new historiographical discourse on human rights has created the third world as a humanitarian problem to be solved. Western attitudes are fostered in the form of a ‘suffering in sympathy’ with the oppressed who are no longer identified with in terms of human rights but on account of individual injury. Slaughter linked individualism, the discourse on terrorism, and the cultivation of acceptable forms of injury to the phenomenon of skyjacking that was prevalent in the 1970s as a focalised repeated trope of individual resistance to Western cultural and economic domination. The importance of 9/11 as crystallising the violence of the dis-embedded individual action of airline hijacking has cemented the discursive shift from self-determination to terrorism almost irrevocably, in a process that has become the ironically mirrored hijacking by the west of the history of human rights.

Following the end of the main lecture, and a short refreshment break, we returned for a Q&A session. The first person to ask a question inquired into the place of ‘citizenship’ within the current neoliberal narrative, and whether it has broken down as an idea in the same way as the self-determination of decolonialisation. Slaughter suggested that if the elided history of the ‘rights of man’ within anti-colonialist literature is complemented by an idea of the rights of citizens, then the new historiographers have created a false dichotomy between citizenship and the more supernational human rights. A concern over someone else’s citizenship is always framed as a concern for Western purveyors of human rights. Citizenship and terrorism are no longer compatible ideas, much as skyjacking came to stand in as an emblematic movement of terrorism even as the West concerns itself with the inequality of economic distribution that gave rise to it in the first place.

The next question asked about the language of equality in the cultural rise of the individual as the centre of ethical choice. Slaughter responded by bringing up the complications on the 1970s as the ‘me decade’, which also saw a proliferation of liberation movements – not limited to second-wave feminism – which were underpinned necessarily by group dynamics whilst always overlapping with the neoliberal individualism that was coming to increasingly define the era. Slaughter informed us that this conflict is made especially apparent when we consider the breakdown of types of rights. Economic rights are easier to square with neoliberalism than social rights as they’re more amenable to a universalised subject. We can see this in the language of Amnesty International which concentrates less on localised or embodied human rights than with a generalised idea of unjust infringement. The primacy of economic rights, which glosses over disparities between national demographics was far more nationally unifying than social rights and contributes, Slaughter suggested to us, to a solidification of Cold War bilateral conflict in the 1970s.

The following question returned to the shifts in the meaning of ‘terrorism’, with reflection on the rapidity of the discursive evolution that led the speaker to ask about how quickly could it shift once again. Slaughter proposed that this question takes us back to the shift in dynamics between states and their citizens and directs us to the power of propaganda’s influence on how we conceptualise and valuate self-determining struggle.

Slaughter raised several other interesting points about the hijacking of human rights. Firstly, how the ‘me decade’ has produced as an effect the genealogical transformation of ‘desire for’ into ‘right to’ that is now the characteristic logic of neoliberalism. This is an effect that can be located within language of human rights that individuals like Brigitte engage with: ‘I have a right to x’ is nearly always a property claim to the point where even a right to an identity becomes a claim to possess a thing no matter how seemingly abstracted. Another question about pan-Africanism brought out how citizenship, within the discourse of human rights, is also a European-centric idea of ethnic self-determination, and thus holds sway over racial and cultural identities. ‘Human rights’ emerges from the 70s as a language which is the only legitimate method of discussing sovereignty, liberation, and determination.

Slaughter ended his percipient Q&A session with a reflection on what position literary criticism might currently have in any discussion of human rights. He proposed that to understand this question, it is necessary to take seriously the fact that literature records ideas about the world. He explained how much of his evidence for an expanded history of human rights has emerged from the literature of non-Western nations, and nations struggling with the very concerns of self-determination, that have recorded a history not entirely commensurable with the genealogy that has been produced in the West. Here, we have developed our philosophising within a passive voice of human rights and intellectual history, a process of free floating and disembodied ideas, which seemingly just happened on their own accord. The missing gaps of history, the influences from outside of the West, are what we are able to recover through a turn to literature, the records of which provide us with a point of departure for productive alternative narratives of history.

(Thanks to Lyndsey Stonebridge for these photographs)

Twitter: @CCLC_bham

Website: https://bit.ly/2DWj1Qg

To join the CCLC maling list please email: r.sykes@bham.ac.uk