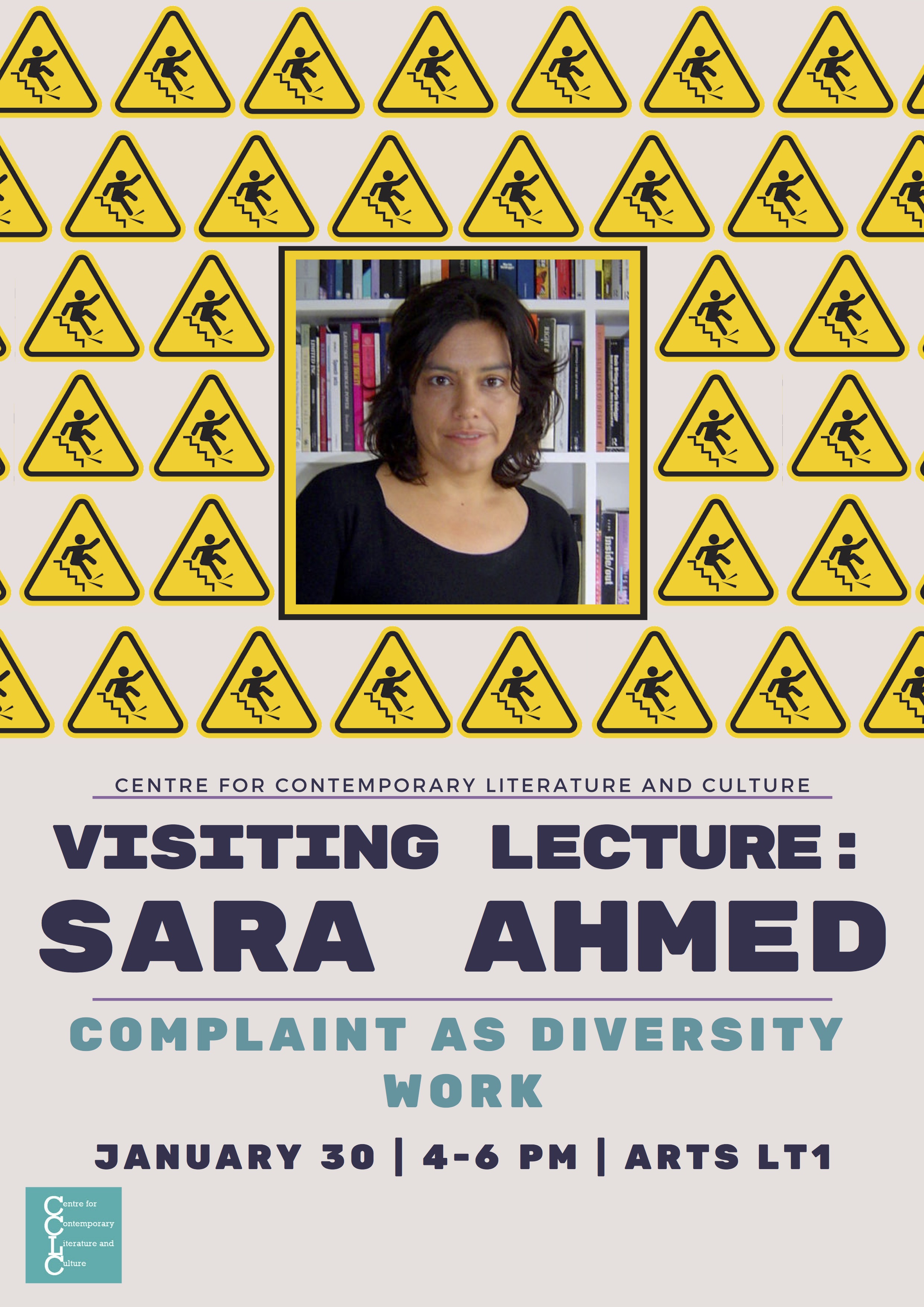

A full lecture room welcomed Sara Ahmed to the University of Birmingham for her talk, Mind the Gap: Complaint as Diversity Work, which would prove to be a hugely engaging and thought-provoking evening. Ahmed’s brilliant talk on complaint was just part of a bigger ongoing project she has been undertaking about university institutions and the experience of complaining. She wants to know what we can learn about the complaint process by listening to the stories of those who have complained and by working with complainers to understand how it feels to go through the procedural rigours of complaining. What can we learn about how unfair and unjust working conditions are perpetuated, and what can we do to confront the problems of harassment and abuse that go on in our academic establishments? Ahmed has carried out multiple interviews with those who have experienced the process of complaining in order to decipher the elaborate technologies that keep abusive dynamics in play and prevent their exposure or transformation.

To begin, she brought up how complaints are often dismissed, and how they then come to be used against the complainer themselves who is often figured as spoiled or as harbouring a grudge. These are just some of the many images of complainers that are produced to minimise oppression both in the workplace and in education. By investigating the complaint procedure itself, Ahmed hopes to recognise, firstly, how it tries to separate people and to isolate the complainer and, secondly, to emerge with new strategies for how complaint might, instead, bring people together in response to abusive structures. Her talk, then, looked also the undermining of communal support: how complaint depletes energy, how it minimises the space that someone feels they can occupy, how its programmes of confidentiality that ostensibly protect an individual actually work to keep abuse and harassment secret and out of sight. Ahmed read these effects into the very physical shapes of the university buildings, drawing on how long narrow corridors and shuttered blinds replicate the isolating and stalling avenues through which complaint has to travel. Her repetitive recalling of these physical barriers – presenting them as endless and unnavigable like Resnais’s opening monologue in Last Year in Marienbad – highlighted the energy and persistence required to keep the complaint procedure moving along and to recreate the university space as more habitable and shareable.

What was instantly noticeable as we heard her speak was her distinctive style. Ahmed’s style has become increasingly eminent through much of her recent written work, both in books and on her blog feministkilljoys, and posits an elaborate fusion of wordplay and reference, including association, metaphor, etymological analysis, extensive chains of reference and connection (drawing richly on the metonymic, the homophonous, the chiastic, the zeugmatic), and a rhythm that underscores the alliterative and assonant power of words. Her lecture acquired a unique and engaging style of address that was conceptually accessible whilst allowing for some challenging experimentation. The connections she produced between words and ideas meant that when emphasising just a single point the traces of her many strands of argument still resonated through the wordplay, and her language was able to hold together the full breadth of her argument as it moved through each section of her lecture. The experimental style brought to the talk an overlapping of feelings – perhaps a belief in the potentially subversive and uncontainable power of words, maybe an overwhelming and frenetic urgency that wants to compel us into action and recognise the severity of the institutional issues, but also, perhaps, in the play and creativity of Ahmed’s own writing, a possibility that we might find some joy in activism even when it seems to call for it to be killed!

The talk itself took to task the laborious and hostile environment of the complaints process that is integral to the operations of many universities and educational institutions, finding in the experiences of those she interviewed a system as exhausting and interminable as even the most Kafkaesque notions of bureaucracy. Her analysis examined the abilities of the process to dismiss and isolate the complainer and to amplify the atmosphere of oppression and abuse that it purports to confront. She relayed to us the techniques through which complaint is made exhausting and interminable, and how it feels to find oneself confronting them. She argued that the difficulty of complaining ends up making complaint about the very process of doing so, and the very act of opening up investigations comes to stand as evidence of the complaint being satisfactorily dealt with and closed. The autotelic processes creates a ‘gap’ – the ‘gap’ of Ahmed’s title – between what is supposed to happen and what actually does.

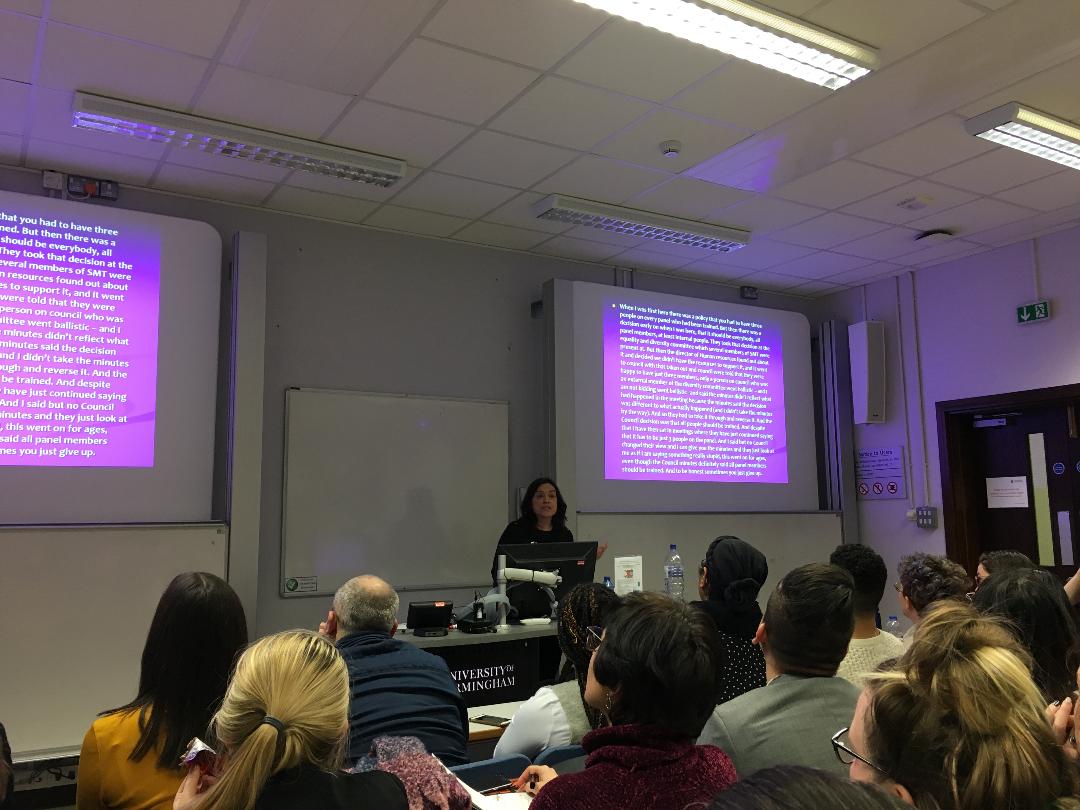

The term under which Ahmed skilfully umbrellaed the system’s numerous techniques to bring about the exhaustion of the complainer was ‘non-performativity’. With this term, Ahmed described those times ‘when naming something does not bring something into effect, or when something is named in order to not bring something into effect’. Institutions often move things around but it doesn’t mean something is actually happening, as manufacturing evidence of action is not the same as doing the action itself. Nodding was one of Ahmed’s great examples. When people agree to what you’re complaining about it can stop the complaint from travelling any further. Nodding along can give the impression that something is about to happen that isn’t – it stops you feeling like you have to continue to say ‘no’ because you’ve reached agreement. Encountering this gap between what you think is happening and what is really happening gives a strong sense of the surreal. From the data collected in interviews, Ahmed has recognised a pattern of feeling that everything you expect to happen next simply does not happen. People around you treat the situation as if nothing is going on at all; it feels as if there’s no narrative or you are a part of someone else’s narrative entirely, and that what is happening is everything except what is supposed to actually be happening

Ahmed made an interesting connection to the power of laughter in situations of abuse and oppression. The joke becomes a highly pressured situation where not participating in the continuation of hostile or unequal working environments is close to engaging oneself into the precarious and powerless position of complainer. The joke is one mechanic through which abuse is allowed to perpetuate. Ahmed explained that by not laughing at a joke we disconnect ourselves from the shared community because laughter often works to hold something together and create a feeling of something shared. By not laughing we refuse to play along and we become alienated. Not laughing can be a form of complaint because complaint is often registered in how bodies do not go along with something shared before anything is ever said or officially logged.

Part of the power of Ahmed’s talk came from her reiteration of the physicality of the universities and how their building can symbolise the obstacles put in place by the institution. Her talk reproduced images of walls against which you feel as if you’re only scratching the surface with a complaint whilst the larger foundations remain unaltered and barricade against any progression. Doors also featured as significant synecdochic representation. Doors can be closed or even locked to impede movement in or out or to keep harassment out of view. She brought up two examples of where harassment was made possible and exacerbated by the locking of doors, access through which can be limited to people with power, privilege, and prestige. Complaint can be directly in conflict with these doors – an attempt to open them and keep things in motion. Doors are an integral part of the university building and are utilisable only by those with the correct keys needed for access, both literal and figurative.

Ahmed’s concluding metaphor recognised the rigid immovability of the university buildings but made sure to emphasise that even they are susceptible to leaks and damage. For her, leaking is emblematic for resistance through the complaint process – as making information public that institutions always want to keep behind closed doors. Data is always held tightly during complaint. Under the name of confidentiality, it works in the role of damage control by controlling the transmission of information. Managerial tricks help to produce the illusion of something happening that really isn’t – new procedural policies might be introduced or polls carried out without any reference to any of the things happening that have led there. Ahmed told us that complaint does not leave without a trace like the processes want it to. Instead, they haunt institutions and its structures of loyalty maintained for damage control. Ahmed proposed that these traces, which she conceptualised as those scratches we leave behind on the wall, might be used for collective purposes – to communicate with other complainers in ways outside of the prescribed systems and for building solidarity in indirect ways. Even as complaint feels like it does nothing, it is connecting us together in ways that might bring about the change we want and need.

QUESTION & ANSWER

The Question and Answer section of the talk introduced other interesting ideas to the consideration of institutional complaint procedures. Some of the most interesting and troubling concerns included how institutions can easily hold judgments about the credibility of complaints based on other values made about the complainer, which is why the most disenfranchised groups so often struggle the most through the procedure. She described how many complainers feel the institutional gaze as a weight that their own complaint has placed on them and how they themselves come to be the object of the procedure’s judgments. The most obvious incident is with complaints made by disabled students or members of staff who find themselves being scrutinised so as to determine whether or not they are who they claim to be.

She also outlined how complaint manages to form communities. Ahmed proposed that the collectives that came to light during her research emerged from the very action of discussing the complaint procedure with others instead of the solidarity we might expect to have formed around the initial abuse or harassment. She explained about how important community was to those who go through the process especially in light of the shock that often comes when the people we most expect to support our complaints turn out to be against us. She gave examples of the ways in which community might be experienced during these situations: in the form of solidarity with other complainers, through pets and animals, or through writing, which Ahmed specially told us was essential not only for herself but for many other feminists of colour who struggle to put their stories out there and be heard.

The final questioner wanted to know more about Ahmed’s style of speaking and her presentation of words in both her written and spoken work. They appreciated the ways in which metaphor allowed for the translation of ideas into accessible thought and they wondered about Ahmed’s specifically linguistic/literary influences. The name that came up instantly was that of Audre Lorde, a poet and activists whose work often confronted what it means to find the right words for an experience. Ahmed has been greatly inspired, she told us, by black feminism and the courage it has found to turn towards those secret places of pain and write about them. She also recognised the importance of, firstly, writing specifically on a blog and, secondly, doing so during a particularly difficult time in her life. She explained that she had wanted ‘words to dance’ because it helped present experience in a new way. She argued, as her last point, that as we document history it is necessary to think about art and aesthetics differently in order to bring out new experiences in our writing.

Twitter: @CCLC_bham

Website: https://bit.ly/2DWj1Qg

To join the CCLC maling list please email: r.sykes@bham.ac.uk