This semester’s Queer and Now reading group, led by Angus Brown, centred around Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders (2018). This new book by Omise’eke Tinsley explores the ways in which black Atlantic sexuality is mediated through the imagery, symbolism and cultural traditions of Caribbean spirituality, with emphasis on the polysemous, multi-formal Ezili, a senior spirit of Haitian Vodou, whose many manifestations have come to represent love, sexuality, pleasure, fertility, and creativity.

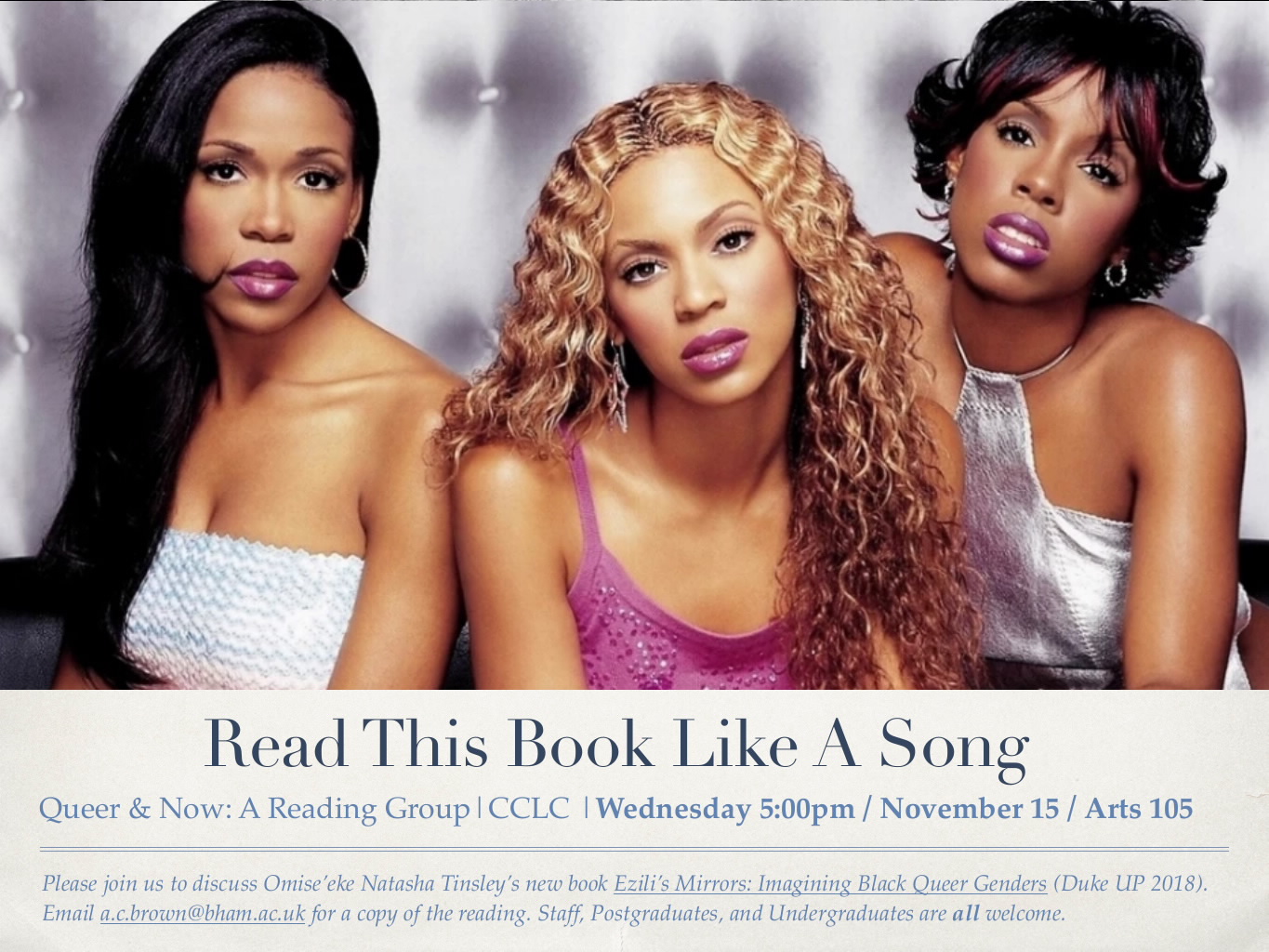

The first part of this cross-genre, polyvocal text that struck us was the fusion of multiple points of view, tones and critical approaches of the individual literary critic, Tinsley, and the balancing she achieved between Haitian Vodou and American popular culture. The three styles of writing – mediated through a constantly shifting font style – echoe in particular the three distinct voices of American girl group Destiny’s Child. The effects of this, we thought, worked to construct transnational bonds between black feminisms. We asked whether this unique style could be understood as a ‘queering’ of the academic voice that is often compelled to meet formal and institutional expectations; instead, Tinsley resists the normative bias towards impersonal, detached, third-person, monotonal styles. We asked further whether this formal experimentation could be interlinked with the autobiographically-inflected tensions that she discusses in the introductory section between conforming to and escaping from twenty-first century academic models, a heritage within which her career and critical framework are heavily entrenched even as it so often subsumes and elides her identity as a woman of colour. The fusion of Western literary criticism with a Caribbean spiritual heritage seems to play out this ambivalence between the two.

In this book, Tinsley includes various passages between chapters that are intended to link them together. She calls these ‘bridges’. Her appeal to ‘read this book like a song’ carries with it more formal techniques from the music of Destiny’s Child to complement her tri-vocal style. But we wondered what exactly it would mean to do just that and read the book as if it were a song. Would it make the disciplinary aspects of literary criticism more flexible in their cultural reach, more amenable for the reader to return to and ‘replay’? The contrast implied between song and academic text is, perhaps, a technique through which Tinsley hopes that the entire binary between professionalism and popular (or less serious, less empirical, even more spiritually abstracted) culture might collapse. It made us ask about the autobiographical work that is so prevalent in queer theory, and what the stakes might be in reintroducing the personal into academia this way, and what new cultural/formal/stylistic avenues it might allow us to use.

Some surprise was expressed that such a text was not as provocative as one might have expected, and that Tinsley did not try to unsettle the Western reader as much as the project could allow. We wondered if this was a departure from the often traditionally polemical queer theory and towards a new type of black feminist criticism inflected by a Caribbean queer background instead, where sexual diversity seems much more integrated into spiritual traditions than in Western Judeo-Christian belief.

The importance of fluidity to the imagery of Ezili was picked up as a particularly queer instantiation of the supernatural, especially her distinct associations with water: water as ever shifting but also water as containing history, as an archive of waste that tells its own narrative about cultural valuation, property acquisition, as well as individual stories of loss and regret. The plurality of figures in Vodou includes not just Ezili but many of their Loa, as well as the mythologically iconic figure of Marie Laveau living in New Orleans, which we felt exemplified for the writer a bridge between Haitian/Caribbean settings and a postcolonial instantiation of Vodou in contemporary America.

Expanding on the ideas of fluidity and water by way of the other traditional Loas, we ended the reading group with a discussion of the overlap between Vodou and queerness that Tinsley finds within the dually-sexed Lasirenn, who is renowned for transmutation of bodily sex and sexual orientation. As a spirit whose fluid sexual and gender characteristics are associated with powerful spirit possessions, Lasirenn seemed to disrupt any concept of one’s self-identity and even collapse subjectivity itself. This was contrasted to the Western mutually-informing conceptualisations of gender and sexual orientation, and we asked whether or not this categorical fluidity afforded by possession was utopian, or whether it was perhaps more invested in fixed notions of genitally-determined sex than we had first realised.

Twitter: @CCLC_bham

Website: https://bit.ly/2DWj1Qg

To join the CCLC maling list please email: r.sykes@bham.ac.uk