As part of CVRO’s assessment of COVID-19 Review, we have carried out an analysis of ‘Prime Minister’s Questions’ (PMQs) during the pandemic. The purpose of the analysis is to track the role of human rights principles and discourse in these weekly Parliamentary sessions.

PMQs as a mode of accountability

PMQs take place every sitting Wednesday from 12pm to 12.30pm and may be watched live on ‘Parliament TV’. The Leader of the Opposition has six question slots reserved for them, while the Scottish National’s Party’s Westminster Leader has two questions slots reserved. A regular part of the Parliamentary process since 1961, PMQs took place twice a week until Tony Blair changed the question sessions to be once-weekly. The principal role of PMQs is to provide a forum for accountability of the Prime Minister. However the extent to which the sessions promote meaningful accountability has been the subject of debate.

Writing in 2016 Alexandra Kelso, Mark Bennister and Phil Larkin described PMQs as an ‘occasion largely motivated by political performance, ritualistic humiliations, and the delivery of headline-grabbing one-liners’. While many have expressed doubts as to whether PMQs meaningfully hold the Prime Minister to account, research by Shaun Benav and John Peter (2015) suggests that PMQs plays a role in setting the Parliamentary agenda and helps both opposition and backbenchers draw attention to issues the government does not always wish to attend to. James Murphy (2014) has argued that the nature of PMQs is ‘highly dependent on the make-up of parliament and that government and opposition backbenchers, as well as the PM’.

While such varied opinion about the role of PMQs exists, the question sessions are among the parliamentary activities most closely followed by the media. The sessions thus represent an important public forum for informing and justifying to Parliament (and through their publicity, the electorate) the Government’s activity, including its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In light of this, we assessed the questions asked during PMQs in the last year to examine how, if at all, human rights feature in this part of Parliamentary engagement with and assessment of the Government’s response.

Approach to the Analysis

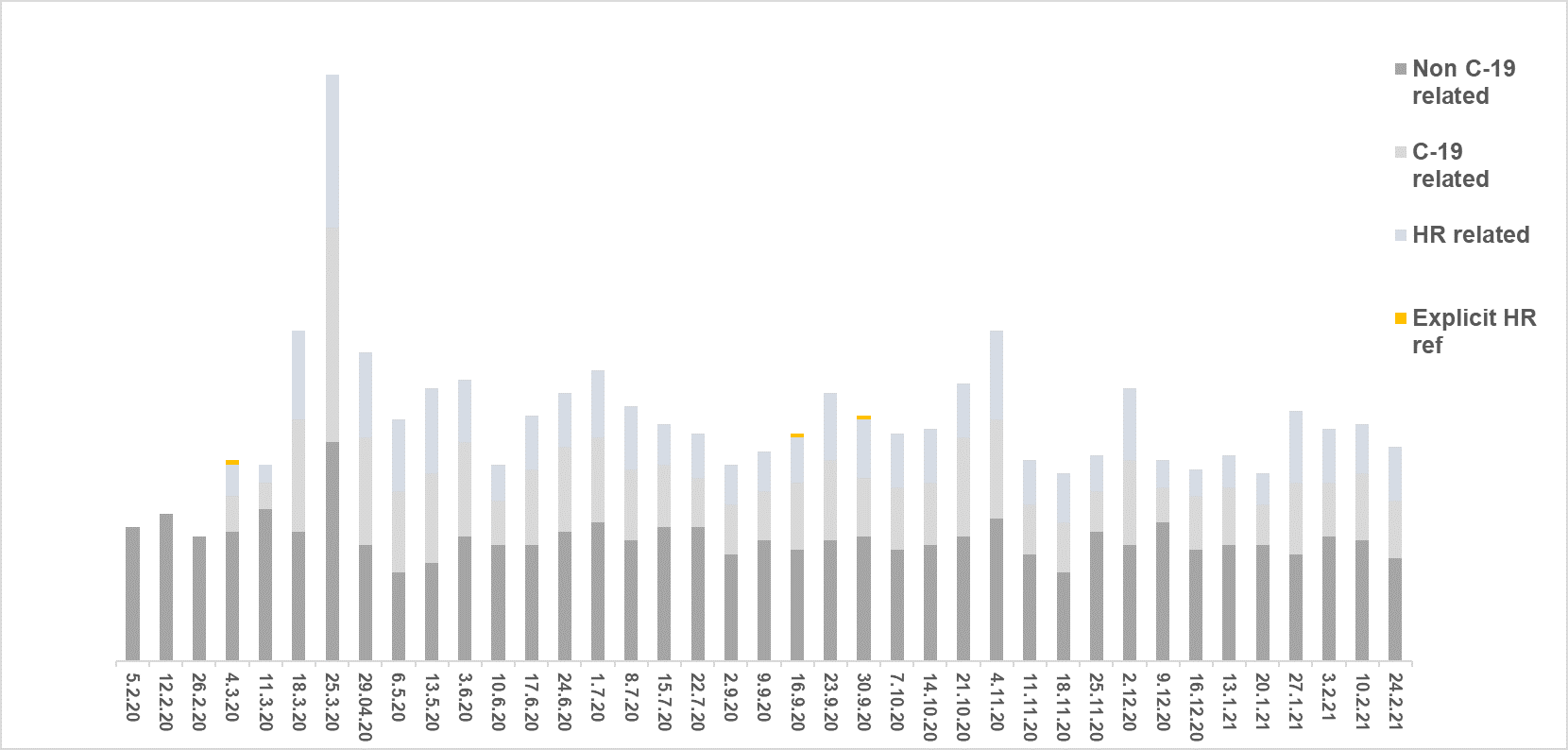

In carrying out this analysis, we assessed Parliament’s engagement with human rights in all PMQs since 30 January 2020, the date that the WHO officially deemed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 a global health emergency. We applied a number of categories to the questions asked. First, we distinguished between ‘COVID-19 related’ and ‘non COVID-19 related’ questions. A question was considered to be COVID-19 related if the questioner expressly referred to an issue in relation to the pandemic. We excluded questions which may have some relevance to the pandemic but which did not mention it. For example, general questions regarding levels of poverty in the UK and universal credit may have some relevance to the pandemic, but where the question was not framed specifically in relation to the pandemic it was not included in this category in our analysis.

We then identified the COVID-19 related questions that were ‘human rights related’. In light of the potential breadth of the term ‘human rights’ we sought to adopt a conservative approach in identifying where questions were human rights related. Where questions related to particular rights provided under the ECHR, or was very clearly linked particular economic and social rights, we labelled them human rights related. This included questions regarding government support for vulnerable social groups, as well as questions regarding access to information related to the Government’s response to the pandemic (for example, the infections rate, the scientific advice upon which a particular decision was made). We excluded questions that were in essence requests to the Prime Minister to reiterate the need for lockdown compliance by particular groups. We have also not taken questions regarding support for private corporations, such as the aviation industry, to be human rights related, except where the need for government support for workers attached to those corporations is expressly raised. General questions regarding the economy have not be categorised as human rights-related.

Finally we identified those questions which explicitly referred to human rights out of the human rights related ones. In identifying such questions we sought to adopt an inclusive approach, whereby any reference to ‘rights’ or ‘liberties’ would be counted rather than merely questions that use the precise phrase ‘human rights’.

What the Analysis Shows

The results from our analysis were as follows:

- Out of approximately one thousand questions asked at PMQs, around half of the question were ‘COVID-19 related’.

- Of these questions, approximately three quarters of questions were ‘human rights-related’.

- Of these questions, making up just over four hundred questions, only three questions explicitly referred to human rights.

Figure 1: PMQs under COVID-19

Figure 2: Explicit Human Rights Questions in PMQs

| Questioner | Date | Question |

| Jeremy Corbyn MP (Labour) | 04.03.2020 | When the Prime Minister brings forward the emergency legislation, will he guarantee that workers’ rights to sick pay from day one—he has just indicated that that will apply on statutory sick pay—will apply to all claimants? |

| Ed Davey MP (Lib Dem) | 16.09.2020 | So before the House is asked to renew the Coronavirus Act, will he meet me to discuss how we can protect the right to care of disabled people and act lawfully? |

| Munira Wilson MP (Lib Dem) | 30.09.2020 | How does renewing the [Coronavirus] Act today in full stack up with his personal mission, never mind his conscience? Will he finally commit to working across parties to replace these draconian laws to ensure that we protect our most vulnerable and safeguard our liberties? |

Discussion

Over a twelve-month period during which there have been substantial limitations on rights enjoyment, and during which the state has had to discharge its positive human rights obligations to (among other things) protect life, public health, education in exceptionally challenging circumstances, the scarcity of rights-engagement in PMQs is striking, even in light of the highly politicised nature of PMQs. The findings presented above suggest that Parliament’s engagement with the human rights impact of the pandemic has been inadequate. Despite so many of the COVID-19-related questions having human rights implications, MPs have not generally referred to human rights or civil liberties in holding the Government to account. It is also noteworthy that none of the explicit human rights questions, set out in Figure 2, were asked by the current Leader of the Opposition, or the leader of the Scottish National Party. This is particularly interesting in light of the Leader of the Opposition’s professional background as a leading human rights lawyer, and the extensive engagement with human rights by both Government and Opposition in the Scottish Parliament.

This analysis suggests that human rights are conspicuously absent from Parliament’s most public forum for holding the Government to account. In light of the many impacts of the pandemic on human rights, the obligations human rights law imposes on Government in responding to the pandemic, and the clear standards of review human rights imposes on the Government, this is unfortunate and noteworthy. Given well-publicised utterances of some members of the Government, including the Prime Minister, that human rights lawyers disrupt good government, it may be read as suggesting that everyday politics in Parliament, of which of course PMQs is emblematic, is inhospitable to human rights framing and analysis. This has clear implications for rights-based parliamentary review during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photo credit: Copyright UK Parliament / Jess Taylor