Looking over your transcriptions of Text 2 has revealed to us something which, in truth, we had already guessed: in general we can see that the level of accuracy of the transcriptions you have done in the last two weeks has improved enormously. We’ll tell you below the areas that have shown the greatest improvement, but first we’d like to thank you all for the thought and effort you have put into the transcriptions and particularly the close attention you have been paying to the finer detail. The results are very positive: Congratulations!

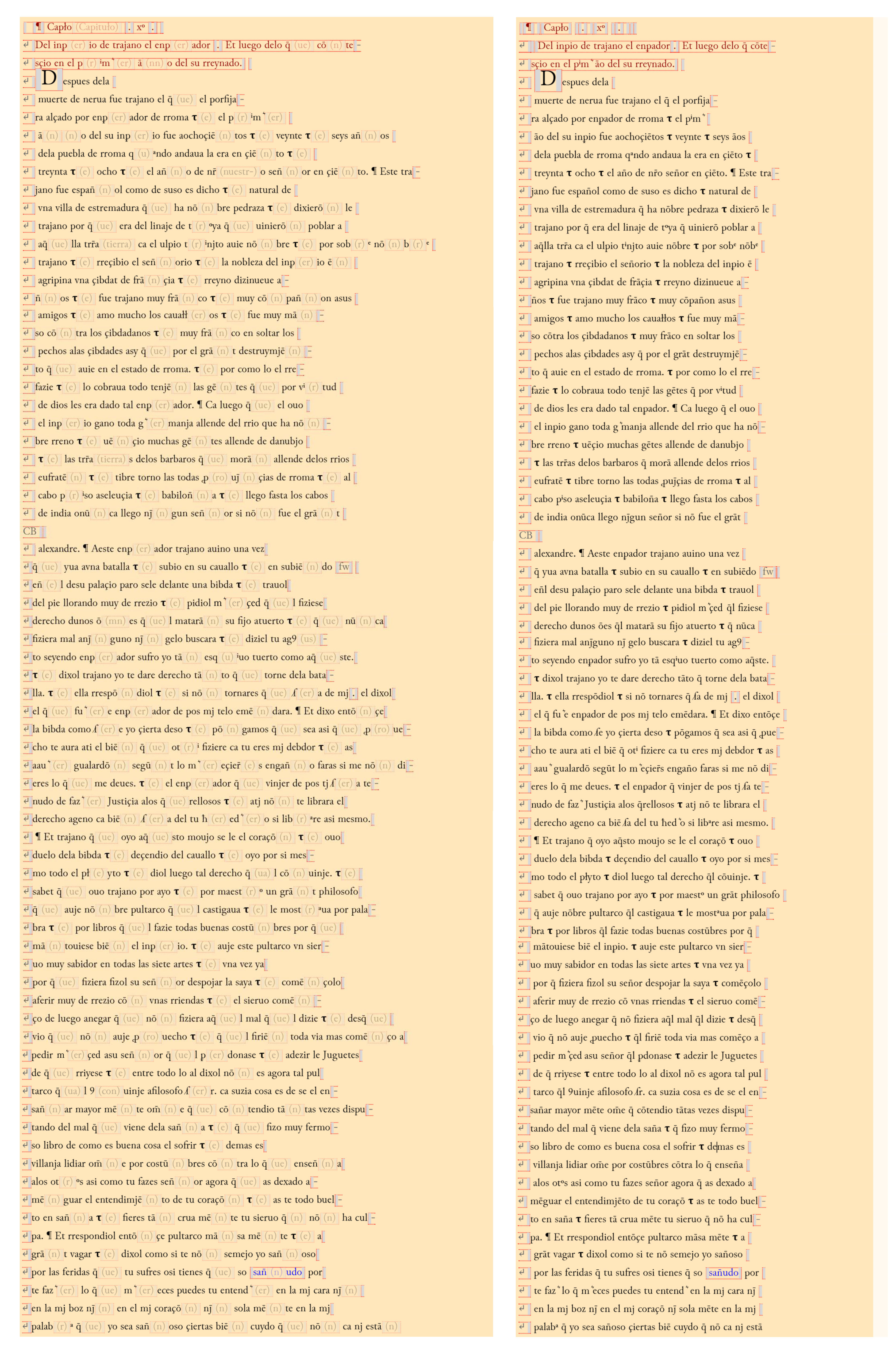

First and foremost, here are the images of the how the correct transcription *should* have looked. You can compare with your own, if you wish, and have a look to see how you did. If there is anything in our transcription you don’t understand, do let us know. These are the correct transcriptions, in both abbreviated and expanded forms:

The first thing to say is that the number of errors related to graphical variation between manuscript C and the base text E1 is gradually reducing. Remember, though, that in our manuscript it is much more common to find variants like <ç> (c cedilla), <j> (used both as vowel and consonant) and <v> (at the beginning of a word). In the case of the first of these (<ç> c cedilla), here are a few examples we found in the transcriptions: *ciertas > çiertas, *cibdat de francia > çibdat de françia, *cibdadanos > çibdadanos. Sometimes the cedilla is not very clear, as in the case of “françia”, but it is there (it’s the little blurred ink mark below the <c>). Any time you see a strange ink mark, however small, your critical antennae should probably take note – because it is almost certainly the case that it has some meaning. In our project, sometimes we are interested in these (as is the case of a cedilla or macron), but equally, sometimes we don’t think they have any particular value for us (for example, the little dot or line which often appears over the <y>.

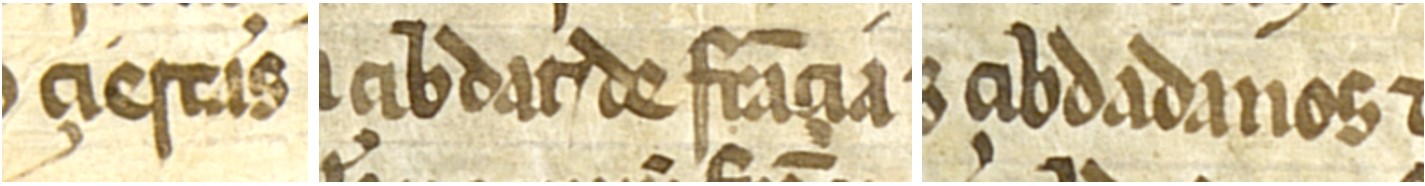

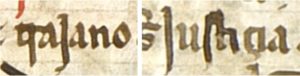

In the case of <i/j>, you will probably also have noticed by now that it’s rare to find words beginning with <i> in manuscript C. Indeed, it’s much more frequent to find a <j> when in the base text (E1) the <i> is used: e.g. *traiano > trajano, *iusticia > Justiçia, *mouio > moujo, *tenien > tenjen.

In the last two examples here (moujo, tenjen), notice how the <j> follows a letter (<n>, <u>) whose shape could easily be confused for two <i>’s, or even an <m> when a <i> is added after them. This is probably why the stroke of the <i> descends below the line to form a <j> – that is, precisely to avoid the possibility of confusion and to make the text easier for medieval readers and revisers. We referred to this in Module 1 of the training course.

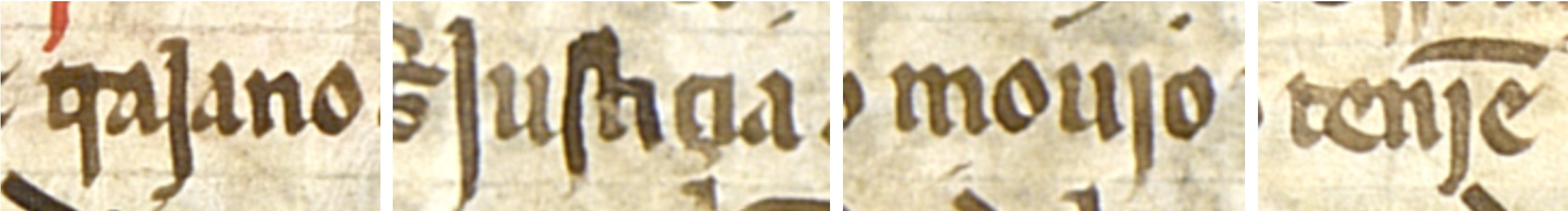

As far as the distribution of <u/v> is concerned, we’ve also noticed that you have paid attention to the fact that manuscript C employs the <v> at the beginning of words, whereas E1 tends to use <u> e.g. : ejs. *uez > vez, *una uilla > vna villa, *un > vn.

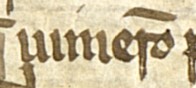

Make a mental note of this graphical tendency of C (and remember the concept of usus scribendi which Polly discussed here), as it is very useful to improve the accuracy of your transcriptions. However, you should also remember that it is a long way from being a systematic rule. The example of “uinieron” is an excellent one in this respect (though it is not the only one of course: uençio, una, etc.): one might imagine, in line with the usus scribendi of the manuscript, that the scribe would write this word with an initial <v> (*vinieron), or that he would extend one or more of the <i>’s to avoid the confusion we referred to above (*ujnieron, *uinjeron, *ujnjeron, *vinjeron). Perhaps you had difficulty in reading the word at all first time round; you could read it as *uuneron, *iumeron, *miueron, etc. But from the context, and with the help of the base text, we know it is the verb form ‘vinieron’.

But why, you may ask, has the scribe not maintained his usual practice by including the initial <v> or internal <j>? We don’t actually know the answer to this, although it is not infrequent for someone engaged in the arduous process of copying to be influenced, however unconsciously, by the writing of the model from which he is copying. Or perhaps there is another explanation…

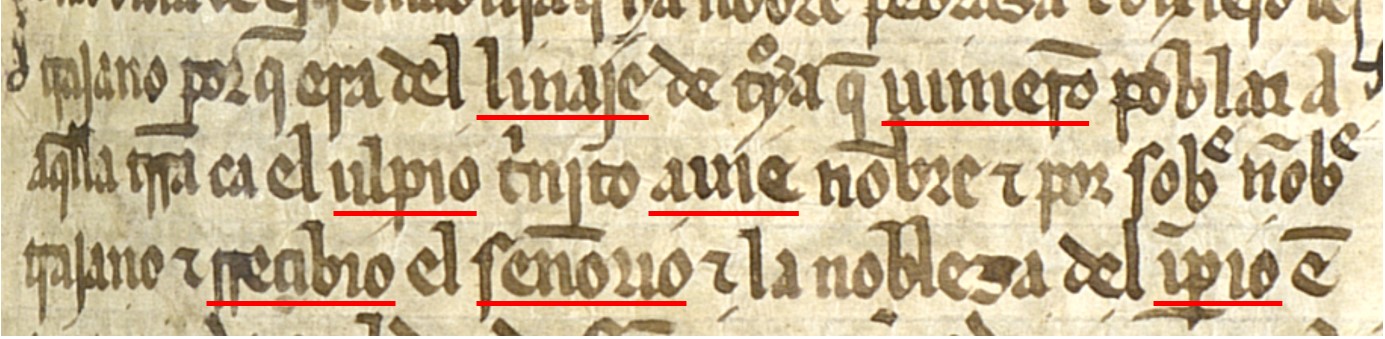

Let’s have a closer look, and if necessary let’s dig the magnifying glass out from that dusty drawer that is never opened. You may not be consciously aware of them, but from time to time you may have asked yourself why there are minuscule marks over certain words. Sometimes they are merely the product of the act of lifting the pen or quill when stopping writing. After all, this still happens to us today when we use a pen (yes, indeed, some people still do this…!); little marks of ink can be left behind when we stop writing. However, if you look closely at the writing in C, you will see that very often (although not systematically) the <i>, and occasionally the <j> and <e> have a small mark in the interlinear space above them which follows the oblique pattern of the letter. In the fragment below, notice how in the words línaje, uínieron, ulpío, auíe, rreçibío, sennorío, inperío include this small diagonal trait. This is known as an apex when it is used as a diacritic to distinguish letters in this way – in this case to distinguish the <i> from contiguous letters. It is not always present, of course, but in forms such as “uínieron”, for example, it can help the reader to distinguish the <i> from the contiguous letters (<u>, <n>), thereby avoiding possible confusion.

Also in relation to the letter <j>, some of you have asked why we transcribe this letter sometimes as <J>, that is, why in capitals and not minuscule? It is a perfectly reasonable question, since we see in the manuscript that the letter extends not just below the line but also above it. The question is also interesting because the difference between <j> and <J> has important implications for the chronology of the development of Gothic script. First of all, however, we have to ask: what exactly is it that we are interested in recording in our transcriptions? The most significant element, as we said above, is that of distinguishing between the <i> which appears regularly in E1 and the <j> which appears in C. The follow-up question might then be: why do we transcribe “trajano” (with <j>) and “Justiçia” (with <J>), if the form of the letter (with its high stroke) is the same? The answer is quite simple, and it has to do with a convention which allows us to avoid further complicating the results of the transcription. When the <j> is initial in a word we transcribe it as though it were a capital (<J>) -even if it is not a proper noun-, and when it is in any other position, we transcribe it as though it were lower case (<j>).

What possible implications could this have for the chronology of script? Well, of you are interested, have a look at this article (by Mª del Carmen Fernández López). In it, she confirms that towards the middle of the fourteenth century, the use of the <J> to represent the voiced alveopalatal fricative /ʒ/ (which has today evolved into the velar fricative /x/ represented by the letter <j>: ej. Trajano) became solidified. This means that it is very unlikely that in the second half of the fourteenth century the sound in question would be represented by any letter other than the <J>, whereas previously, as is the case of C (from the early decades of the fourteenth century) there is a greater variety of spellings: <i>, <j> and <J>.

All of this may seem insignificant to you, but in reality it is all important information to help us understand the evolution of sounds and graphs over the years. So: don’t let your guard down! It’s difficult to transcribe and maintain concentration so that when you compare C with the E1 base text you spot all of the variants and make the transcriptions as precise as possible. But we are achieving this, so well done!

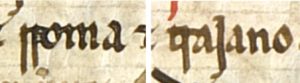

Before entering the world of abbreviations, two quick final notes on graphical questions. We still notice, albeit to a lesser extent than before, that some transcribers tend to regularize words according to current orthography, or perhaps, through inattention, fail to correct the orthography of the base text. We note this especially in the transcriptions when the modern use of upper case and lower case letters is employed. If in the image we see “rroma” and in the base text the form “Roma” appears, it is tempting to leave the current capital letter where it is. But in fact, we have to substitute the upper case <R> with what is the usual spelling in C to represent the initial trill, that is <rr>. Something similar happens with “trajano”, which we all tend to leave with the uppercase letter from the base text (*Trajano), when in the image we see a lowercase initial letter.

Finally, we will get around to talking about abbreviations – we know you love them dearly! In the first instance, we should say that we have noticed a significant improvement in the use of the correct macron from the abbreviations menu: we no longer see the confusion of <n> for <ue> so often (e.g. *qn > que). And we can say the same thing for the omission of the macron completely (e.g. *no > non, *fraco > franco); this was a very frequent error in Text 1, but now has all but disappeared.

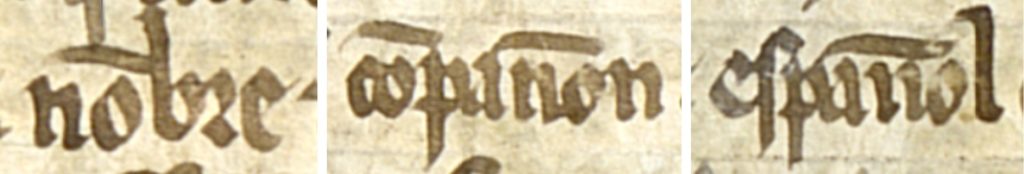

Also reduced, but definitely still there, is the use of the expansion <m> before bilabial consonants <p> or <b>). Remember that the usus scribendi, the tendency of the scribe, in this case is to interpret the macron as <n> and not <m> as in modern usage, thus: *nombre > nonbre, *compañon > conpannon. Remember also that in this last case, or in the case of “espannol”, the palatal consonant should not be transcribed in the modern fashion (<ñ>: *español), but rather following the practice of the scribe: <nn>. So in this case, you should select the first <n> and add a second one using the <n> (n-macron) in the abbreviations menu, thus: espan̅(n)ol, co(n)pan̅(n)on.

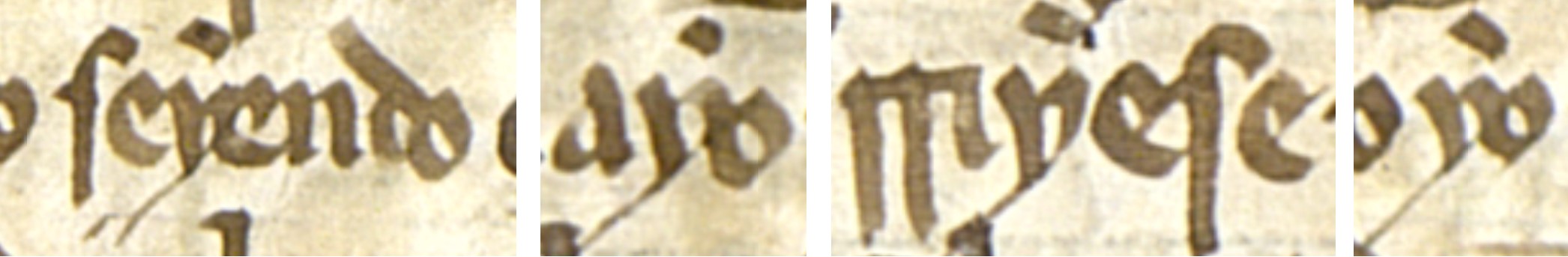

We have also noticed that there continues to be some confusion over the transcription of the word “como” when it has a macron. As we mentioned previously in the blog and also in the training, we are not interested in the presence of the macron here because we think that in this manuscript it has a decorative rather than abbreviative effect. In contradistinction to the Alfonsine manuscripts (and other thirteenth-century codices), in which the form “commo” appears with no abbreviation and with two <m>s, in the fourteenth century it seems that the presence of the macron has no abbreviation function (*commo), but rather it is merely an obsolete mechanical practice which fossilizes previous practice. In consequence, when you come across this form, you should just transcribe it as “como”, whether it has a macron or not. This, then, is an exception to bear in mind, rather like the dot or bar over the <y>, which, as you know, we also do not transcribe: “seyendo”, “ayo”, “rriyese”, “yo”. This is simply another variant form of the letter which we don’t represent in our transcriptions.

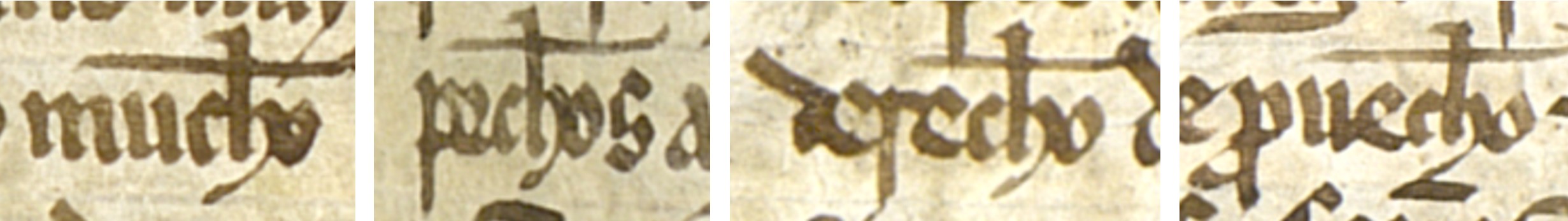

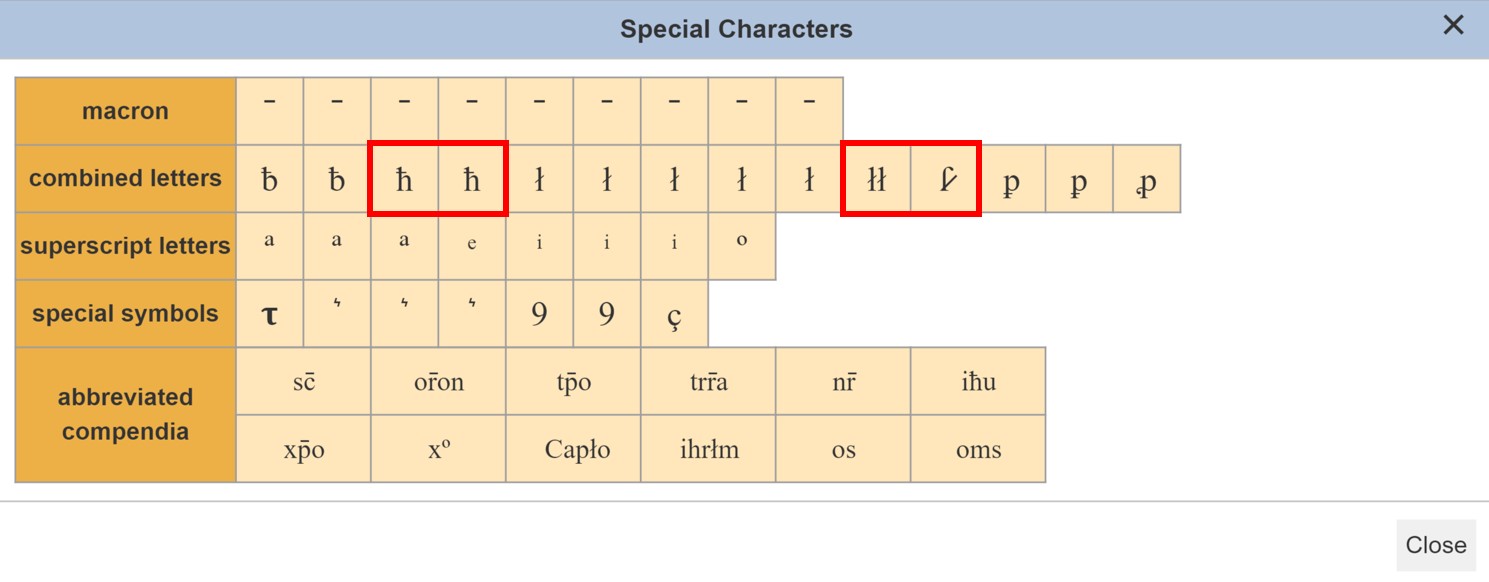

The example of “como” is not the only one when we ignore the presence of the macron. Various transcribers have asked us what they should do in the cases shown below: “mucho”, “pechos”, “derecho” and “prouecho”. Here, the macron has no abbreviative value, but rather serves a decorative function. If you notice, in each case the macron crosses the ascender of the <h>, but is not abbreviating anything, unlike the case of other words with the same mark: “ħmano” (hermano) or “Ioħn” (Iohan). This is fairly common practice in the middle ages, and it is increasingly evident in the fourteenth century; becoming more so as writing gets more cursive. The only possibly doubtful one is “mucho”, for which there is a variant “muncho”, but even then we transcribe the word as “mucho” given the widespread decorative value of the h-bar in the manuscript and the absence of examples with the variant “muncho”.

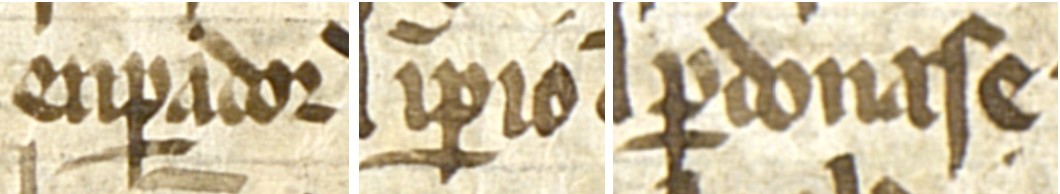

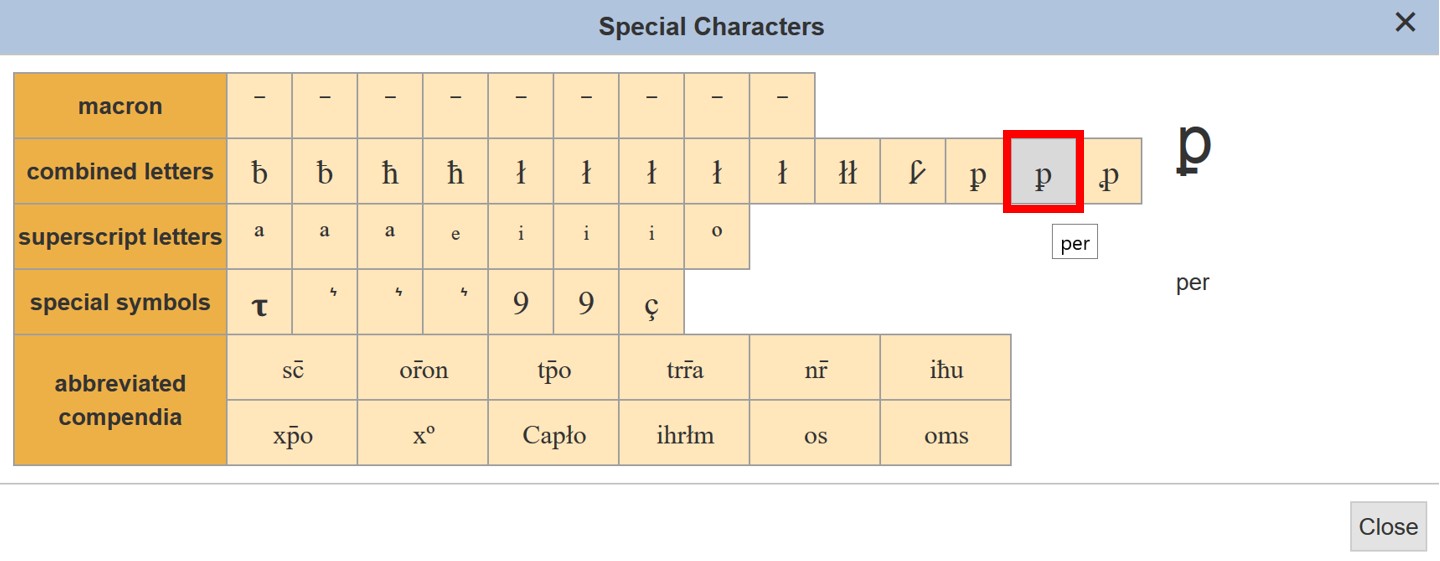

One more comment on the use of abbreviations in the transcriptions: some of you have had difficulties when choosing the correct abbreviation for the expansion ER. For example, in the word enperador, some of you have omitted the abbreviation (*enpador) and others have done so, but incorrectly (*enp ͛ador). In this last case, the expansion is correct, (enperador), but the abbreviation is not: it is not the hook ( ͛ ) which appears in the list of abbreviations in the “special symbols” line, but rather the crossed <p> (p-bar), which you can find in the <combined letters> line. So the correct transcription is “enꝑador”, which would appear as enꝑ(er)ador in the expanded version. You can see the same use of ‘ꝑ(er)’ elsewhere in Text 2 in the words “inꝑio” (inperio) and “ꝑdonase” (perdonase).

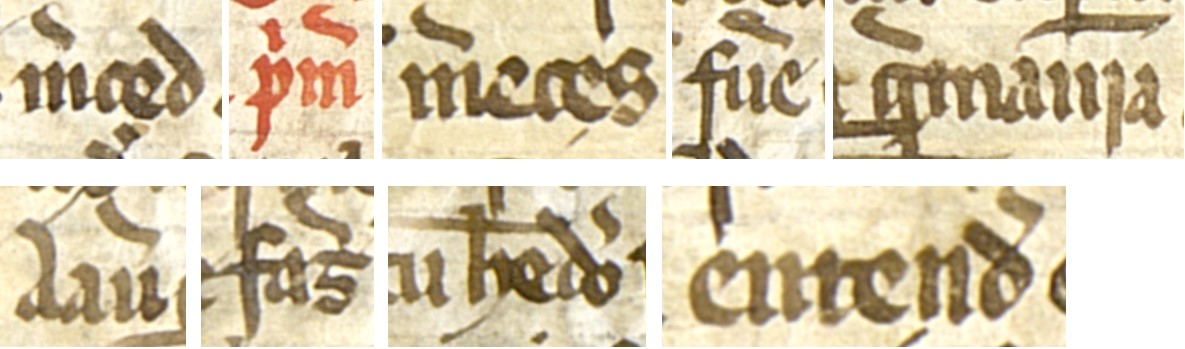

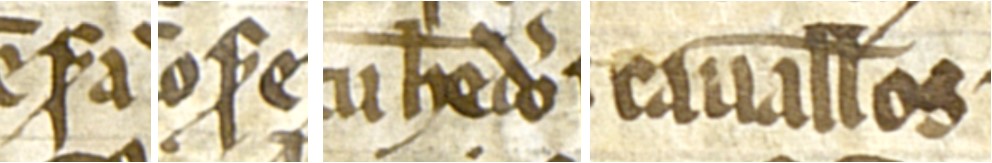

You have also spotted the abbreviation of ER in other words in Text 2 which use other abbreviation symbols. The most common of these is the aforementioned interlinear hook ( ͛ ): m ͛çed (merçed), prim ͛ (primer), m ͛ eçes (mereçes), fu ͛ e (fuere), g ͛manja (germanja), au ͛ (auer), faz ͛ (fazer), ħed ͛o (heredero), entend ͛ (entender).

Have a look at the images above. In the second example you will see that in the word (primer) there is also a superscript <i> to represent the sequence pri-. In the following example (mereces) you might notice that, in contrast to the usual practice of C, there is no ç: (*mereçes). And finally, in the case of germanja, you should notice a macron at the end of the word. But don’t be deceived! It is in fact the p-bar of the word written in the line above. We’ll discuss the case of heredero below.

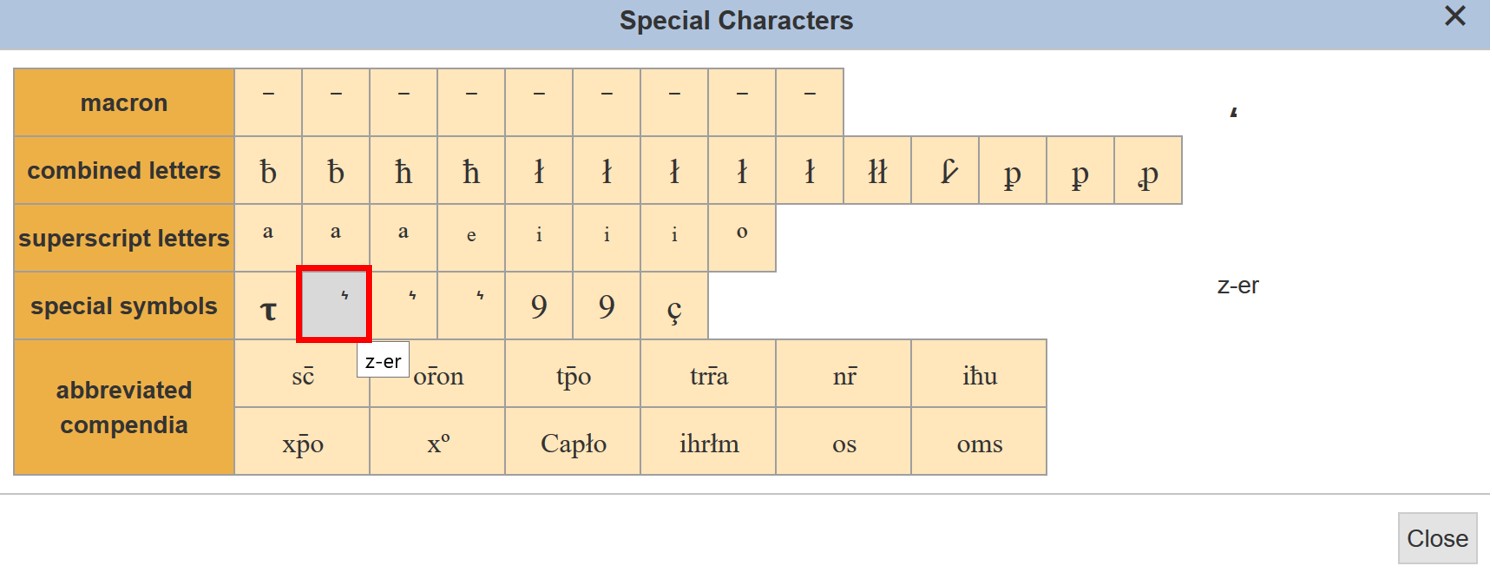

Remember that you can find the symbol ( ͛ ) in the line of “special symbols” in the abbreviations menu:

There is one other way in which ER is abbreviated in Text 2: the use of the macron combined with other letters, such as the high <s>, the <ll> or the <h> (all of which have a high ascender): ſ̷e / ſ̷a (sere, sera ‘seré, será), cauall̅o (cauallero), ħed ͛or (heredero). We saw this example above, because in the same word there are two different ways to abbreviate the sequence ER: the crossed <h> ħ: (her-) and the interlinear hook (-d ͛o > -dero).

Remember that in all of these cases, in order to insert the abbreviation is by selecting the syllable (her, ser, ller, etc.) and then selecting the appropriate symbol from the menu of special characters, generally in the line of “combined letters”.

We’ll end this post with a couple of examples of copyists correcting the text. Some of you have expressed doubts about how to transcribe these phenomena in our transcription platform. You can find more details about this in Module 4, and in the quick guide to the system (on the Training tab of Transcribe Estoria), but we’ll do a quick recap here also.

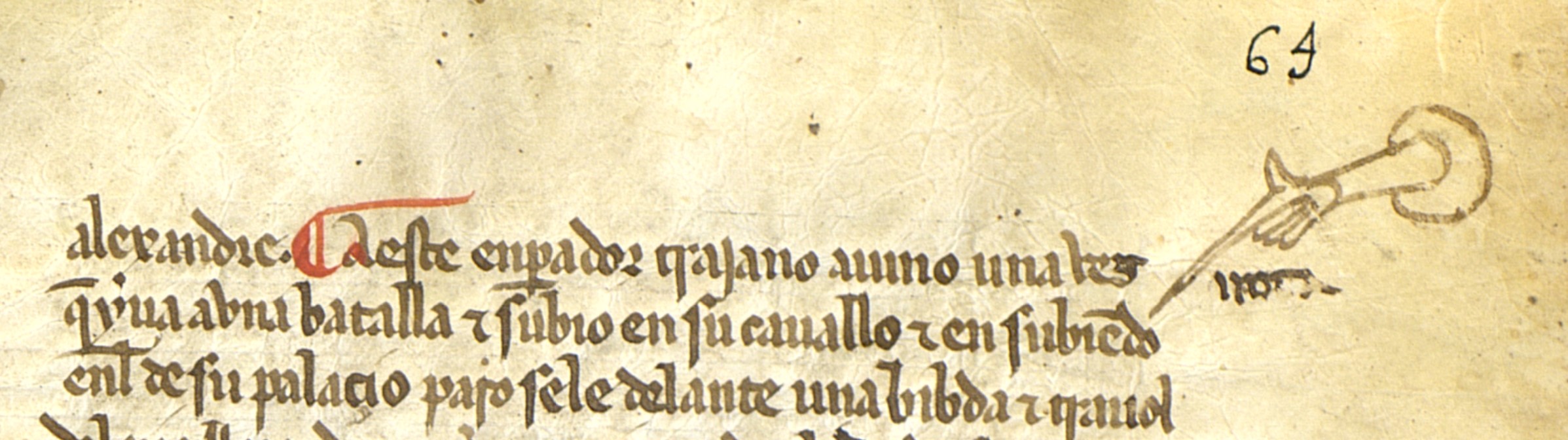

The first of these corrections is easy to see because the scribe/reviser points to it using a beautiful manicule (at the end of the video for Module 2, we discuss this case). He uses this to indicate a word that was copied incorrectly, for the scribe copied “subiendo” and not “saliendo”, which is what appears in the base text E1. It’s possible that the confusion is due not only to the graphical similarity between the two words (subiendo / saliendo) but also to the word subio which appears a little earlier in the same line (“subio en su cauallo e en subiendo…”). Below the manicule appears the word “nota” and one might ask why no-one has corrected the mistake, by means of overwriting, scraping or deleting, since someone has clearly noticed the error. Is it possible that the scribe did not, in the end, want to emend this discrepancy with E1? It’s certainly possible, because the word subiendo fits perfectly well into the meaning of the phrase: “subiendo en el [cauallo]” (although it is also true that the same idea is here repeated in a different manner: “subio en su cauallo” + “en subiendo en el”), while E1 emphasises the leaving of the palace: ‘salir de su palaçio’. We will discuss this soon in a further blog post, which will refer to other corrections made by the scribe(s).

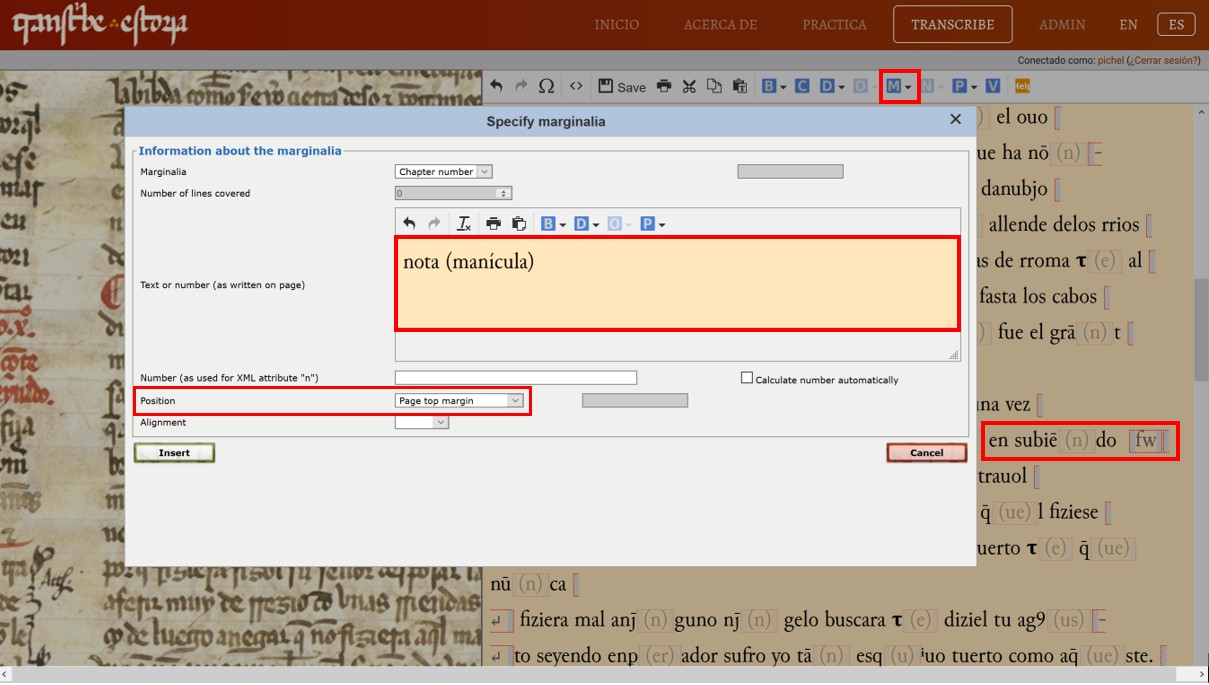

The question remains: how do we indicate this in the transcription system? In fact, this is quite straightforward. Since the form subiendo was not, in the end, corrected by the scribe/reviser, we can use the Marginalia (M) menu in the top menu bar to indicate the presence of the manicule and the word “nota”. In the pop up window that appears, we just have to indicate the text that appears in the marginal annotation (“nota”) and also indicate the presence of the manicule. We can then choose the most appropriate option in the “position” box; in this case “page top margin”. Then click on <insert> – you can pass over the rest of the options. In your transcription, you will now see a red box (‘fw’), and if you pass your mouse over it you will see the information that you just entered in the dropdown menu. By doing this, you will help us by identifying a marginal note that has a significant corrective value – so it is very useful when we compare the text of C with E1.

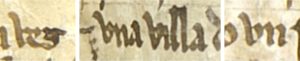

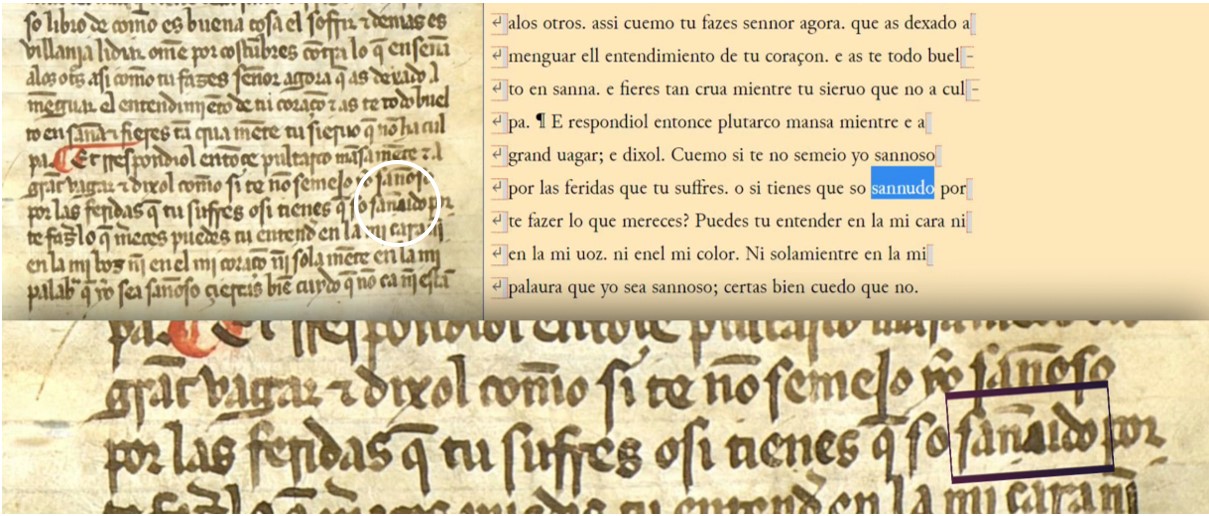

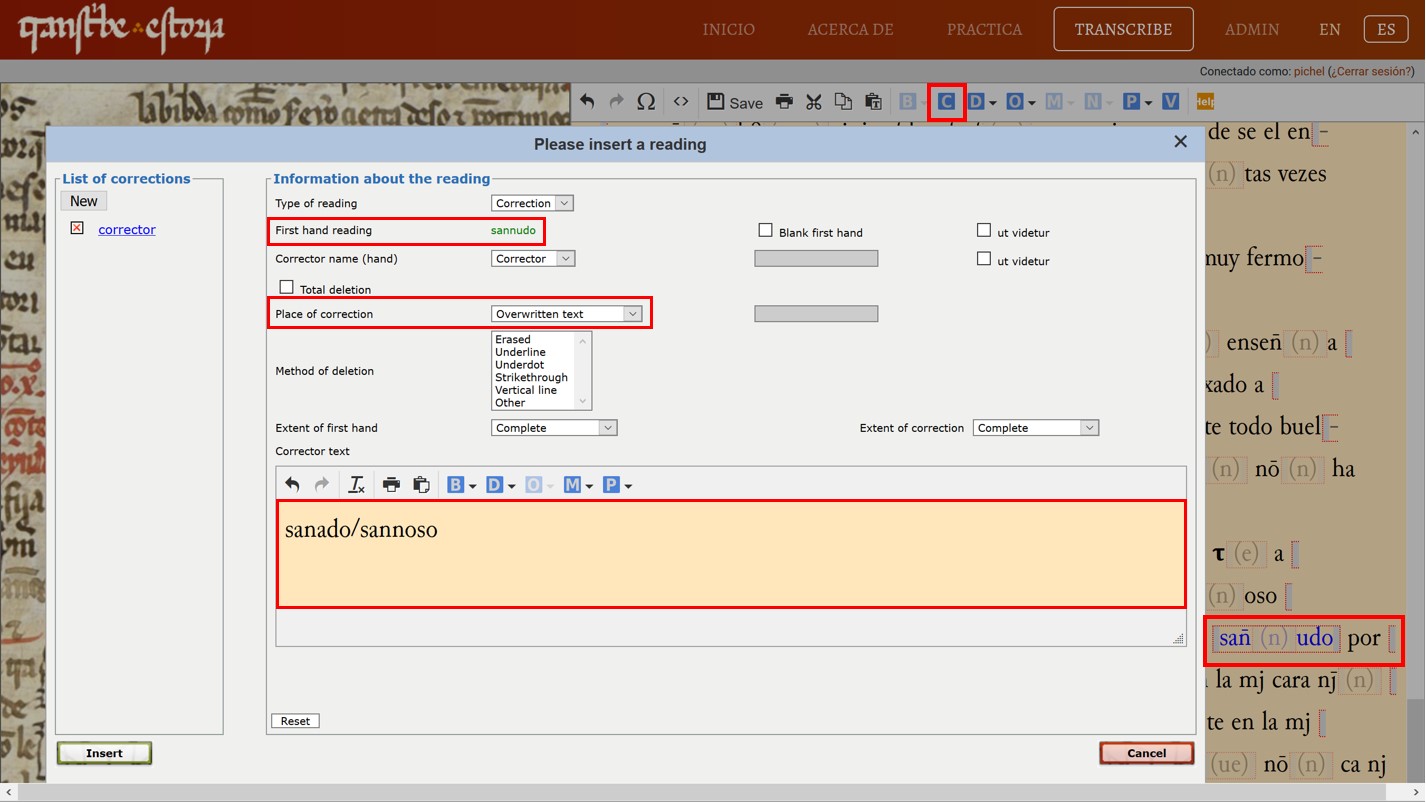

Here is another example of correction, this time towards the end of Text 2. As we mentioned in Module 4, the word “sannudo” was corrected. If you look closely, right beside the <n> it seems as though someone wrote a rounded letter, perhaps an <a> or <o>. Perhaps the scribe was thinking of the word “sanado” or he got confused with the form “sañoso” which is just above in the previous line.

In any case, it is straightforward to indicate this correction in our system. Select the word, or sequence, which is the object of correction making sure not to select the space before or after the word/sequence concerned – of you do this, the menu won’t appear. Then click on the Correction option (C) in the menu bar. In the top of the box which appears (where it says ‘first hand reading’), the word or sequence you have chosen will appear in green (in this case “sannudo”). Further down, where it says ‘place of correction’, you should indicate where the correction has taken place. In this case, there is something written in the word in question, so we choose ‘overwritten text’. Then, without paying any heed of the other options, we indicate in the text box the word which we think was originally written, that is, the erroneous form which was corrected (in this case it could be sanado or sannoso, as we said above). Don’t worry if you don’t know the exact form which was corrected. The important thing is, whether you are 100% sure or not, if you indicate the presence of a correction we can go back over it afterwards. As soon as you have introduced all this information, you can click <insert>. You will see that the word sannudo now appears in blue, and if you hover over it with the mouse you will see the information you put into the window.

Just to be clear though: don’t worry if you are still not fully confident with the use of the Marginalia or Correction menus in our transcription desk. This is normal, because they are the most advanced of tasks and it takes practice to become truly proficient. In any case, this is a pilot project, and so we are trying out a range of different options on the desk with the aim of improving them in the next phase of the project. So if there is one thing you can be sure of, it is that without your help, none of this would be possible. So please don’t get frustrated or lose confidence in your work because it is really helpful for us and for the future of the digital edition of the Estoria de Espanna.

Polly Duxfield, Ricardo Pichel and Aengus Ward

1 thought on “Text 2: review of your transcriptions”

Comments are closed.