Here at transcribeestoria we hope that you are finding the transcription desk easy to use – let us know how it is going in the comments section, or @EstoriadEspanna on Twitter or Facebook.

The third text is again from the Roman history section, and it doesn’t even mention Spain at all! It concerns events of the fourteenth year of the empire of Constantine. A previous chapter in the Estoria de Espanna (chapter 322 – you can read it in the Estoria Digital) recounts the events by which the Emperor was converted to Christianity. It is one of the longest chapters in the entire chronicle. This one concerns the search for the True Cross, carried out by Constantine the Great‘s mother, Saint Helena.

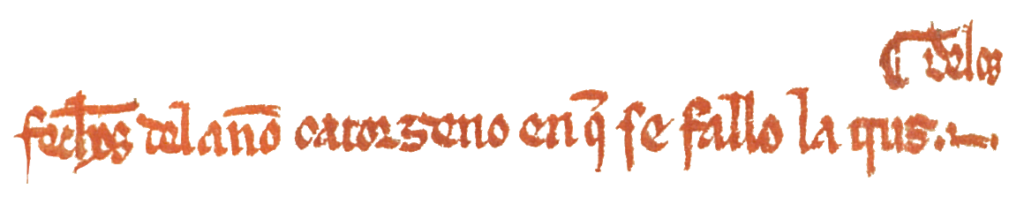

326 Of the events of the fourteenth year, when the true cross was found.

1 In the fourteenth year, which was the year of the era of three hundred and sixty, it happened that the very holy empress Helena was in Rome, and Our Lord God sent to her in visions over and again a command that she should go on pilgrimage to the land of Jerusalem and she should seek the cross on which he had been crucified. And she went there and started to look all over, but it was very difficult to find, for the local leaders had put in the place that Our Lord had been crucified an idol of Venus, 2 so that it seemed that those who came to pray to Our Lord seemed to be praying to Venus; and for that reason the Christians started to move from there, so that the knowledge of where it was was gradually lost, and no-one could tell the empress Helena where the cross could be found. 3 But she, who was so determined, asked around so much that she found a Jew by the name of Judas who told her that he had heard his father tell him about how Jesus Christ had been crucified and had shown him that place. 4 And so Helena went there with many others and she had the idols and all the other bad things that were there cleared away. And she ordered them to dig in the place Judas showed them and they found three crosses there. 5 And although the cross of Our Lord had the plate that Pilate ordered to be written on it, it was so old that it could not be distinguished from the others; so the empress Helena with so great a wish to know which was the True Cross, began to pray to Our Lord that He should reveal which was His. And it happened that one of the principal ladies of that place lay so ill that she was more dead than alive. 6 The bishop of that place was then a very holy man, and when he saw Helena so troubled, he said: “Bring here those three crosses which you found and we will go somewhere I can show you, where Our Lord can reveal which of these crosses is His”. 7 The queen and all of the other people went with him to the house where the lady lay ill and they went in. And the holy bishop prayed to Our Lord on his knees and said: 8 “Lord, You who deigned to save the lineage of men, by shedding the blood of your blessed Son, and Who asked this holy queen to come in search of the blessed cross on which hung our salvation, tell us now which is your cross, so that this sick woman will be cured of her sickness when we touch her with it.” 9 So they put one of the crosses on her and nothing happened, and then the next one but to no avail, and then they put the third one on her and she arose then healthy and cured and overjoyed, and she began to go though the house giving thanks to God. 10 And Helena, on seeing this, realised her great fortune and she ordered that a splendid temple be built at the place where the cross had been found. Then she returned to Rome and gave to her son Constantine the nails which had been hammered into the feet and hands of Our Lord, and he made of them reins for his horse and a helmet for his head. 11 And Helena also gave her son part of the wood of the cross, and the other part she placed it in an ark of silver and gold and put it in a convent of virgins, where it was always honoured and guarded. 12 And on the day that the ark was given, Helena invited all of the women of the convent to eat, and she herself served them while they ate, for she did not want anyone else to serve them. 13 Of the fifteenth and sixteenth years, we can find nothing worthy of recounting, except that Constantine the emperor was made Caesar.

As we have seen before, the narrative is encased in chronological references. Although you could see this passage as free-standing, the compilers have clearly situated it in the chronicle as a whole, and this reminds us of the relationship of past and present. In passing, you might note the end comment which refers to two years in which, to all intents and purposes, nothing happened. Or rather, nothing of note happened. This is important, because it tells us that the elements of the chronicle are chosen deliberately, as being of significance for the overall narrative of history which will come to a halt in Alfonso’s own time. The absence of anything to recount therefore emphasises the importance of what is here, as far as the chroniclers are concerned.

So what exactly do we understand from the tale itself? This is especially relevant given that, as we said, there is absolutely no reference to Spain. What does this chapter, or the previous lengthy one, tell us about the history of Spain, in the mind of the chroniclers?

The answer almost certainly lies in the place of Christianity in the thirteenth century. Alfonso was creating a vision of the history of Spain in which he was the inheritor of a long line of legitimate rulers. A signficant element of this legitimacy was of course the profession of Christianity. Constantine was instrumental in Christianity becoming officially indivisible from the Empire, and Alfonso regarded himself as an emperor in direct line from Constantine. The role of Christianity in the history of Alfonso’s Spain is clearly very important. But it is not unproblematic. With the possible exception of the Cantigas de Santa María, all of Alfonso’s own works were secular, and he had signficant conflict with a number of Popes in his desire to be Emperor. Nonetheless, the Estoria de Espanna is here telling us how central Christianity is in a place and at a time far removed from the events that are recounted. There’ll be more about these, and related, questions in future posts.

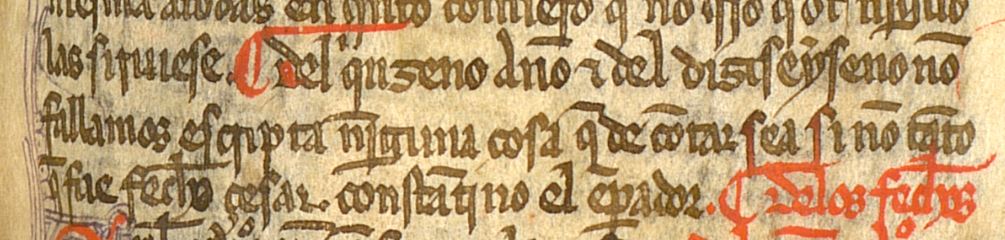

As always, keep an eye out on the physical features of the manuscript as you transcribe. We’ll have a blog post about some of these features tomorrow. Have a look at the use of the red pilcrows in this passage. You’ll probably recognise this character from wordprocessing documents. Do you think they are a help to understanding this passage or perhaps a hindrance? Or are they just there at random, as far as you can tell?

Good luck with transcribing!