Let’s not pretend otherwise: text 5 was the most difficult to transcribe, was it not? While it is the case that there were few extra-textual elements to note (hardly any scribal corrections for example), nonetheless it is probably the most extensive fragment of our five and the one which contained the greatest variety of abbreviations – or at least the text with the greatest number of exceptions, so far. But…let’s not get ahead of ourselves, perhaps not all of you thought this when you were transcribing. For this would mean only one thing, which you have probably already noticed: your transcription skills are now way beyond what they were when you began, 1o short weeks ago, when you were probably unsure about your own abilities and the level of competence that we would demand of you. Now look where you have got to! Congratulations to all of you who rose to the challenge of transcribing with equal parts of hope and perseverance. From here at transcribeestoria we have seen you trip up and improve through practice. We are very proud of your achievements and we consider ourselves very fortunate to have contributed to them – and all the while we were learning about the needs of the transcriber and the good (and bad) sides to our transcription platform.

In fact, as our pilot project comes to a close, we are now a little nostalgic (actually, a lot nostalgic…). However, we are convinced that you will stay with us, one way or another, as we face up to the challenge of transcribing this and other manuscripts in the future. But… there is no room for sentiment right now – there is still work to do and there is always something new to learn. All your efforts have recharged our batteries and in 2020 we hope to return to the fray with new transcription suggestions, new manuscripts and new activities: for example, we’d like you to join us in the Sala Cervantes at the Biblioteca Nacional de España to see our beloved manuscript C of the Estoria de Espanna (BNE ms. 12837: we guess you know this by heart by now…) in the flesh, so to speak. We have been studying it in person in some detail over the last few weeks (it has shown up some surprising features…), and we would like to be able to show it to you in person. Do you dare? 😉 If so, we’ll be in touch at one point in the near future to invite anyone interested to join us in the examination of the Alfonsine heart of our project!

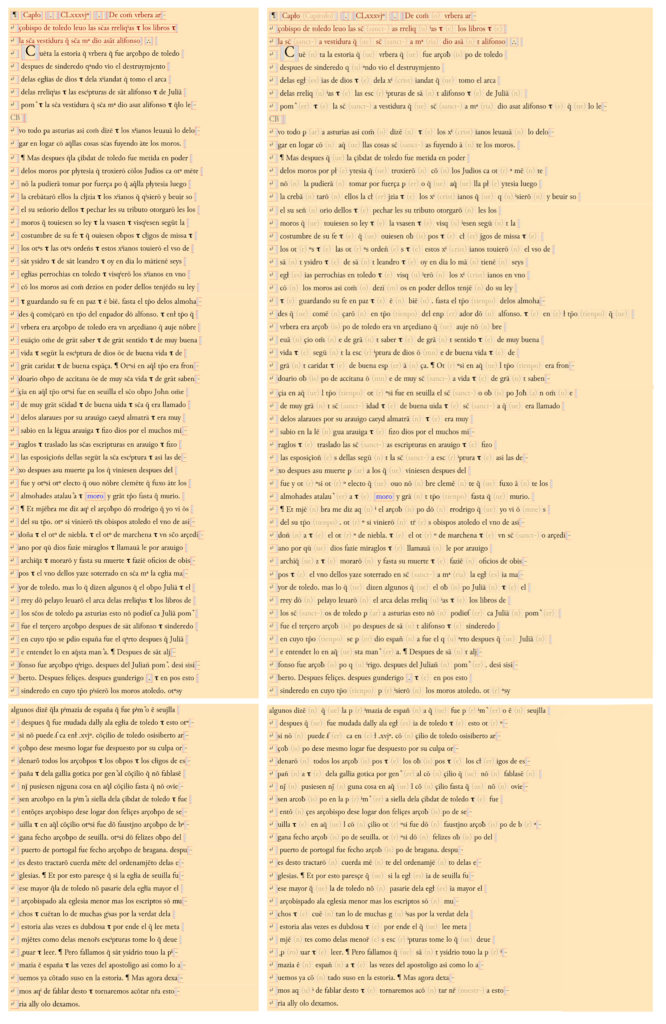

Well, enough of this, and back to work! What can we tell you about your transcriptions that you do not already know? Not much, to tell the truth, because you have all improved incrementally text by text. And we can see this also in the frenetic activity of those of you who have taken on the challenge to transcribe freestyle. But, there are still a few interesting things for us to tell you. First of all, as always, we produce below an image of the corrected version of Text 5, in both abbreviated and expanded forms, for you to compare with your own transcriptions. If you see some discrepancy with your own versions, feel free to let us know.

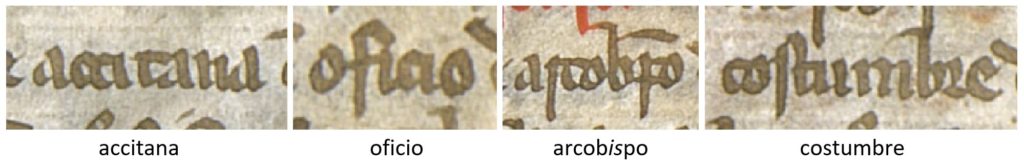

We don’t want to bore you with the usual details about the usus scribendi of manuscript C, since you probably already know these by heart: <v> at the beginning of words , <ç> cedilla before <e> or <i>, nasal consonant before <p> or <b>, etc. etc. You’ll have heard about these already so many times before… But let us at least guess what you are thinking: it is true, you can always find exceptions. The ç of manucript C is sometimes missing, either through error or through the influence of the manuscript being copied: e.g. accitana, oficio, arcobispo. And what could we say about that marvellous example of “costumbre” (with an <m> before the bilabial consonant)? Don’t worry (were you worried? 😉 ) there are just a few isolated examples like this, contrary to the general scribal usage.

Ah, the scribes…! How many took part in the composition of the manuscript? Well, in truth, it is something we could only figure out by transcribing the entirety of the codex. We believe there is more than one. We imagine you will have noticed some different graphical and abbreviation practices in Text 5 to those that you have been accustomed to in previous texts. One such example is that of “como” which is abbreviated here (com + macron > como) in contrast to the usual practice of writing it out in full with the vestigial macron we have seen elsewhere. But this is not the only occasion we have seen it. Do you remember the vestigial macron we saw in forms such as pechar, fecho or muchos? Its presence is probably to do with a tendency, still seen occasionally in C, to put a horizontal line through the ascender or descender of some letters. This happens particularly when the letters are becoming more cursive, and also for aesthetic effect. Of course, this means that there is no reason to transcribe the form “mu(n)cho”, which appears frequently in thirteenth-century manuscripts, since the same stroke appears in other words with no abbreviative function, such as in the cases of pechar or fecho mentioned above.

You can see how much we like macrons… We never shut up talking about them!

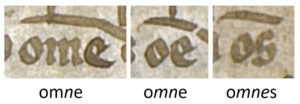

In Text 5, we can also see different ways to abbreviate “omne/s”: the usual om(n)e and two others often required by the space (or lack of it) on the line: o(mn)e y o(omne)s, that is,”oe” y “os” with a macron. It would surely be pretty much impossible to abbreviate a word even more than this…?

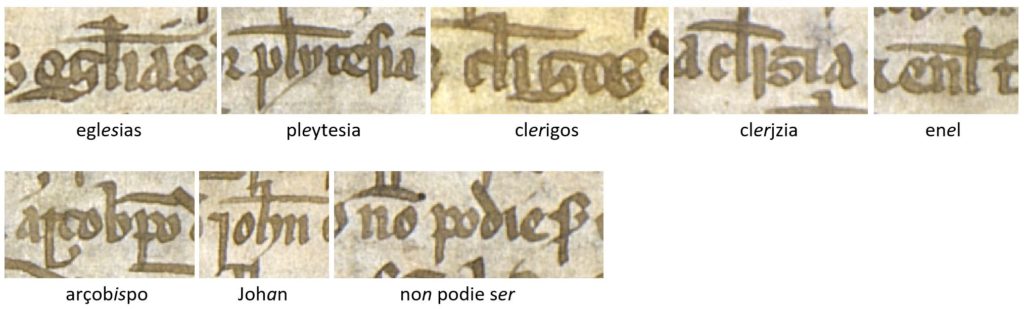

How did you get on with the form in which <l> is crossed by a macron?: egł(es)ias, pł(e)ytesia, cł(er)igos, cł(er)jzia, en(e)ł. Remember that in these cases you can use the combined abbreviation ł, with the exception of the last of these, which can also be transcribed with a macron over the <n>: en̄(e)l. Of course, the word (arço)bispo, (not exactly rare… it appears in the fragment more than 20 times!), is almost always abbreviated with the same procedure (the macron crosses the <b>: oƀ(is)po), and you could say something similar for the form Joħ(a)n. And while we are at it, don’t forget the line through the tall <s> ſ̷ (er) ‘ser’: In E1 it appears as seer, with the double vowel (> lat. SEDERE), but in C we can probably transcribe this form with a single <e>.

Another abbreviation peculiarity of this section (and which may be an indication of a different scribe) in the line where we commented above about the form com(o), is the greater use of the macron to abbreviate the vowel <e> (e.g. orden(e)s, esposiçion(e)s, tr(e)s, menor(e)s, etc.) and -beware, this one is new!- the consonant <m> in an entirely new context: dezi(m)os. We were especially struck by this one when we were transcribing – were you too?

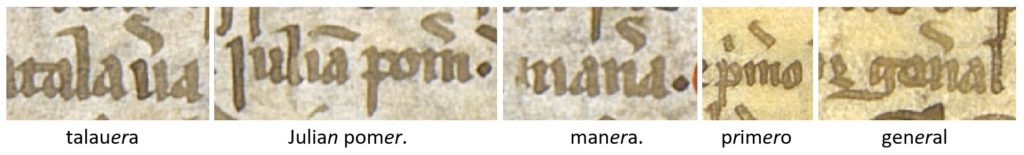

Something else: this one is almost a classic! At this stage we can see that you know the difference between the interlinear symbol to represent <er/re/ir> and the macron or superscript letters. In this fragment, we found several examples of the latter symbol to abbreviate the sequence <er> in interior or word final position: talau(er)a, pom(er), man(er)a, prim(er)o, gen(er)al. The <r> accompanied, either before or afterwards by a palatal vowel (and especially <e>) is one of the most common abbreviation sequences all through the Middle Ages.

Text 5 also allows us to have a systematic look at one of the most interesting graphical/phonetic changes that can be seen between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. We’ve mentioned this a few times before; most of the time you’ve come across the sequence -(n)d in E1 you have seen that it appears in C as-n(t): segund > segunt, grand > grant, caridad > caridat, entended > entendet, cibdad > çibdat, uerdad > verdat… It is a really noticeable difference in this period, and it may indicate a phonetic change in some cases. It’s a phenomenon which requires detailed study, because we don’t really understand the chronological or geographical limits of this variation (assuming there are any, of course). If you are interested, have a look at, for example, pp. 140-144 of Cómo editar los textos medievales by Pedro Sánchez-Prieto Borja (Arco/Libros, 1998). We could also discuss other differences between E1 and C, which are more or less systematic, such as the presence of <ss> rather than <s> in many words (desse > dese, usassen > vsasen) or the adverb estonces > entonçes, but them we think you would probably stop reading and return to the more interesting task of transcribing 😀 Fear not, we will continue for a bit, but only to minimize the effects of your transcription addiction (and if you are now addicted to transcribing, it probably means you are doing it very well!)

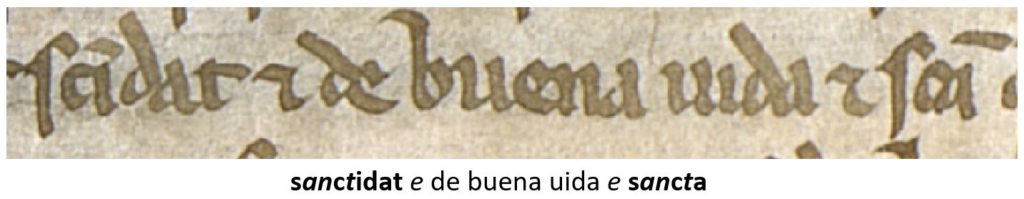

We’ve left the best to the end: that incomplete abbreviation which probably drove many of you mad: sanct- y nuestr-/vuestr-. You already know why we didn’t add this one as a complete abbreviation (or other parallel cases, such as sanct-idad). In order not to clog up the palette of abbreviations in special characters, we choose only to include the root common to all of the words in question. But it’s important that you always leave these outside the abbreviation, thus sc̄os > sc̄(sanct-)os, sc̄idat > sc̄(sanct-)idad. It helps to transcribe in the expanded version, because then you can see the effects of the abbreviations you have included.

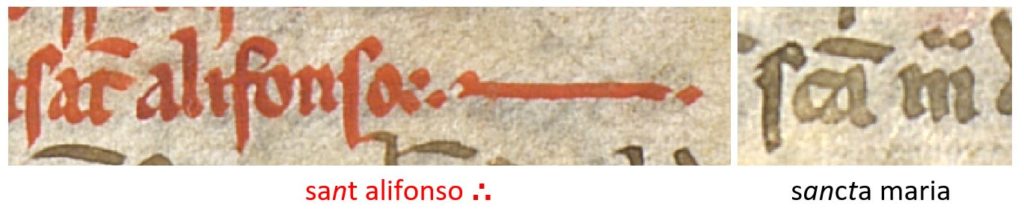

A final little comment for those of you who are aficionados of medieval punctuation (and who is not…?). In this fragment we again came across the abbreviaton of the name María. Remember that in this case you have to select the third option of superscript <a><a>: mª > mª(ria). And… -we know you have been waiting for this one…! – at the end of the rubric there is a beautiful tripunctus ⸫ which can be added into the transcription through the top menu (P ‘punctuation’ > add). By the way, don’t despair if you can’t mark the whole rubric, from the initial pilcrow to the tripunctus at the end, through the top menu (O ‘ornamentation’). It’s not you, it is a limitation of the system which does not allow the inclusion in the rubric of punctuation marks at the beginning or end of rubrics. If you select solely the textual sequence, just as in the corrected version above, that will be sufficient. It is something we will try to improve in future versions of the platform.

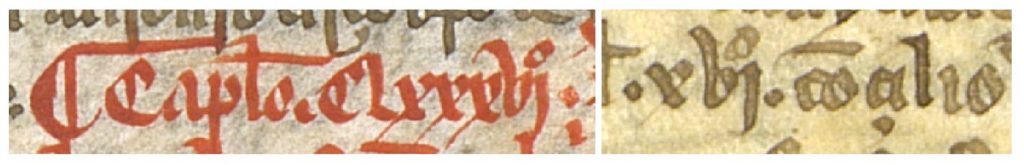

We’ll finish up with three things which you have drawn our attention to in the last two weeks. The first of these is the transcription of Roman numerals: .CLxxxvjº. (fragment 1), .xvjº. (fragment 2). Don’t forget to distinguish, where possible, between upper case and lower case letters, and to include the demarcation points at the beginning and end of the sequence and the superscript vowel. You can use your keyboard to enter these.

A few of you also commented on the strange cruciform symbol at the end of line 18 in column b of the first fragment. It doesn’t really have any textual function; it is really just there to extend the text to the end of the line – so we don’t have to put it in our transcriptions.

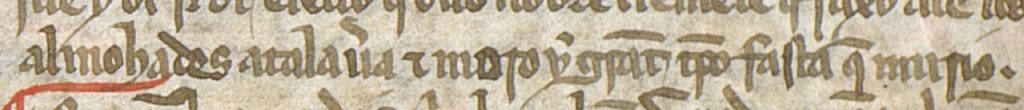

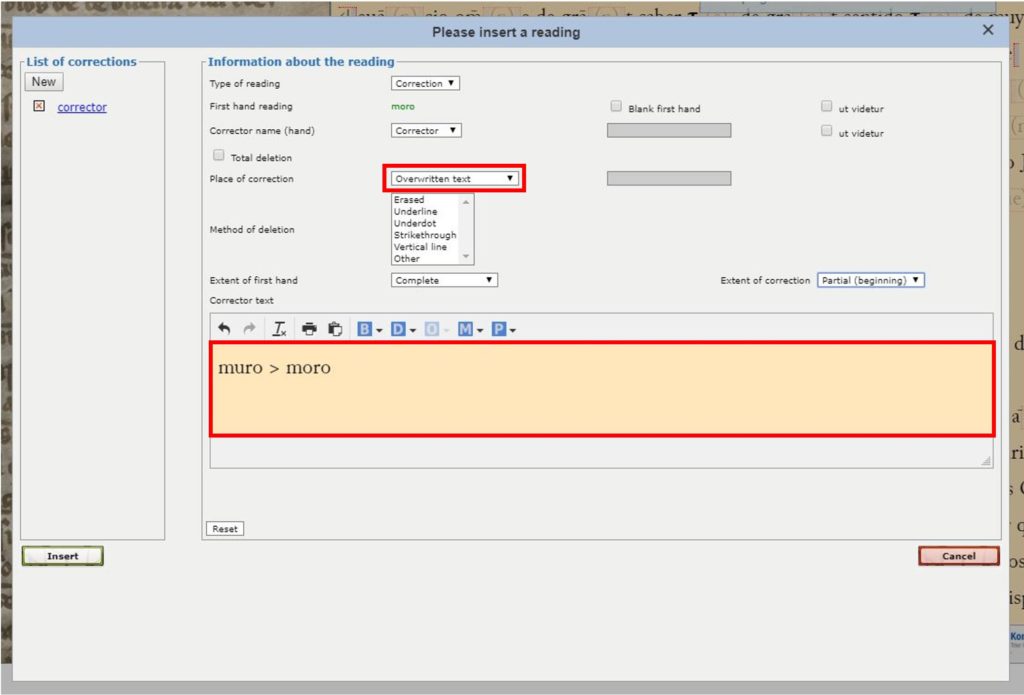

Some of you also noticed a subtle correction in the first fragment (col. b, l. 29): “almohades atalauera e moro y grant tienpo fasta que murio”. The second letter of the verb form moro ‘moró’ was altered, probably by influence of the form murio which appears at the end of the same line.

The way to mark this in the transcription desk is through the upper menu C ‘Correction’, having previously selected the entire word (moro). In the pop-up window, it is sufficient to indicate the place of correction (‘overwritten text’) and in the box below type the corrected sequence (e.g. muro > moro). The main thing is to indicate to the system (and us…) the presence of a scribal correction.

And one final, final final comment; on the way in which copyists modified the textual model they were using. Have you noticed that, despite the general tendency of the scribe(s) of C to abbreviate very widely, at times there are lines which, for whatever conscious or unconscious reason, they occasionally copy lines *without* abbreviating? Oddly enough, this occurs from time to time in this section. Perhaps it is a characteristic of the scribe that is copying this part of the text, or maybe it is simply the influence of the source text exercising an unconscious effect on the scribe. Have a look at l.16 of the second fragment (col. a): “arçobispado ala eglesia menor mas los escriptos sō mu[chos]”. Does this not seem amazing to you? Maybe we are exaggerating a little, but if there were not a macron on the verb so(n), this would be pretty much the first line we’ve come across with no abbreviations at all. were you tempted to add a ƀ(is) a ł(es) or a superscript <i> in the forms arçobispado, eglesia or escriptos which are abbreviated so often in other parts of the manuscript? If the answer is yes, this might be the moment to have a break and get some fresh air – while celebrating the end of your baptism of fire into the world of medieval writing, you can reflect that you have started to sympathise so much with the medieval scribe that you have started to anticipate his movements!

Then you can say to yourself: “It has definitely all been worth while!”

Ricardo Pichel, Aengus Ward and Polly Duxfield