Dr Amy Burnett (LPIP Place Fellow), Dr Jason Leman (Citizen Network) and Dr Daniel Ozarow (Middlesex University) examine how town and parish councils could play a central role in making devolution work for communities. This discussion paper was developed following the National Association of Local Councils’ Power Shift Conference and responds to the English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill. In particular, they reflect on the implications of a neighbourhood governance pathway on the configuration of democracy under the emerging devolution landscape on town and parish councils.

Town and parish councils – the democratic layer closest to communities

Trust in local democracy has consistently remained much higher than trust in national government, and democratic participation increases the closer government is to where people live. The Government’s English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill proposes strengthening regional government through mayors with greater powers and creating strategic combined authorities. This would abolish district councils in favour of unitary authorities. Under the government’s devolution proposals, there is a clear pathway towards neighbourhood-level governance, which may include sweeping administrative changes to create larger ward sizes. Therefore, the underpinnings of representative democracy at the ‘lowest tier’ of government will be significantly impacted.

About 10,000 town and parish councils already exist in England, covering 91% of land but only 36% of the population. These are the smallest tier of government, with elected councillors managing local community assets, supporting community groups, and feeding into strategic decisions made by larger local authorities. This makes town and parish councils particularly important in discussions about devolution – yet they are barely mentioned in current proposals. Whilst the Bill (initially submitted to the Houses of Commons) mentioned “community” 650 times and “mayor” (inc. Mayoral Authorities) 1,824 times, “parish council” appears just 4 times.

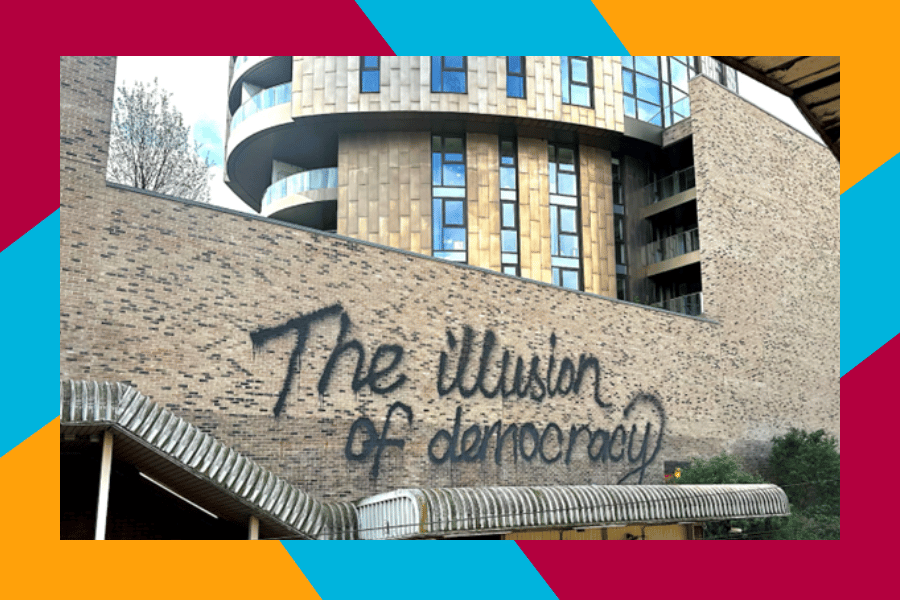

A democratic deficit in the making?

Larger ward sizes arising from a shift to unitary authorities will mean significantly fewer local authority councillors per resident. Unitary councils facing severe financial pressures won’t have the staff or councillors to engage effectively without independent structures that empower community voice and activity. There is a risk that strategic priorities of larger areas will be pitched against smaller communities, perpetuating “David and Goliath” battles between urban and rural areas, large organisations and local communities. But town and parish councils offer ready-made governance structures to bridge “local” level community and “meso” government layers. In our discussion paper, we reflect on the role these entities might play to both articulate and broker place-based and strategic goals – if properly resourced and recognised. We also consider what lessons can be drawn from the challenges and opportunities facing town and parish councils in the context of suggested changes for neighbourhood governance under Clause 58 of the Bill.

The funding vacuum

Parish and town councils gain their main income from their precept – the amount added to Council Tax and allocated directly to them. Under the General Power of Competence from the Localism Act (2011), town and parish councils have enormous potential power to transform local communities – provided that certain conditions are met, such as having a trained clerk. Example frontrunners like Frome Town Council demonstrate how strong leadership can lead to transformative actions in sustainability, food justice and placemaking by building community capacity. However, a third (32%) of parish and town councils had a precept of less than £10,000 in 2025/26, leaving little after administrative costs. Some share a part-time clerk but essentially operate as voluntary groups.

The transition to unitary authorities has arguably created what we identify as a “funding vacuum” at neighbourhood level, where unitary authorities struggle to provide anything beyond statutory services. Transferring assets and services to town and parish councils could be an opportunity – but this comes with risks if not properly resourced.

Three opportunities for change

Our paper identifies three key opportunities to strengthen town and parish councils in the devolution landscape:

1 – Strengthen skills and resourcing to facilitate community capacity

Town and parish councils perform a crucial role as place-based connectors of people and organisations. Where national programmes seek to strengthen community capacity through investment, these councils offer the infrastructure to democratically administer and coordinate this. Future training could refine their role as effective community organisers, whilst regenerative funding models supporting social and environmental goods could encourage proactive outcomes.

2 – Consider the potential of technology at small scale

It takes a particular kind of dedicated or interested individual to attend a parish meeting, let alone scrutinise council minutes. Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models could analyse council minutes for themes, key actions and funding opportunities, reducing burden on staff. These could also increase public engagement and community engagement with Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise organisations. Digital platforms for place-based mapping of local issues and livestreaming meetings could support accessibility. However, technology must accompany, not consume, community conversation processes.

3 – Critical reflection on power in the community

Town and parish councils need tools to sense-check who exercises power and influence, and how to foster greater inclusion. Examples of successful democratic innovations like community assemblies or participatory budgeting need building upon. Model standing orders could consider how to embed democratic innovations, such as transferring decision-making powers to community assemblies. Critically, reflective governance shouldn’t become an onerous task but should support honest and transparent communication.

Bridging the gap

The small print of the Devolution Bill offers suggestions for new rights, powers and a focus on neighbourhoods – including more powers for town and parish councils to support local businesses and include social value in commissioning. To support this, government should develop complementary funding mechanisms operating alongside the Community Wealth Fund that enable wider community involvement in decision-making and better integration with existing resource opportunities (such as Section 106 and the Community Infrastructure Levy), creating a more comprehensive architecture for community wealth building across different neighbourhood contexts.

Making devolution work locally

Devolution won’t fix distrust in politics through administrative efficiency measures and top-down neighbourhood convening alone. The empowering – and creation where they don’t exist – of a layer of government at the scale of towns, neighbourhoods and parishes is essential. A principal authority-run engagement process can tend to favour that authority’s interests, or be perceived as doing so, which risks reducing legitimacy as the convenor of locality. Organisations like the National Association of Local Councils and Locality are calling for town and parish councils to be included as key partners in shaping proposals for new unitary authorities, with We’re Right Here also proposing Community Covenants as “a new model of partnership between councils and local people”.

We stress the value and importance of town and parish councils under devolution and how they must be integrated into any future form of neighbourhood governance arrangements, such as ‘neighbourhood areas’ in Section 60 of the Bill. Currently, this states that these need to be established by local authorities but it is unclear whether who and what will set them up and how the managing of these multiple layers will be carried out.

Town and parish councils can be the democratic voice and mechanism for delivery of action from communities, being the hand that reaches up to grasp that which is reaching down from the “meso” level of unitary and strategic authorities. As place-based convenors of action, they can support the voluntary and democratic lifeblood of our places. However, their role – while being of a voluntary nature – can be overly formalised and there is opportunity to think how their roles can be reimaged, appreciated and supplemented with new democratic governance arrangements to embed the historic and committed role that parishes and town councils have played over generations in English democracy.

The question is whether current devolution proposals will recognise and resource this potential, or risk creating an even greater democratic deficit at precisely the moment when communities need stronger local voice.

This blog was written by:

Dr Amy Burnett is an LPIP Place Fellow and Research Fellow at Middlesex University’s Centre for Enterprise, Environment and Development Research (CEEDR)

Dr Jason Leman is Neighbourhood Democracy Lead at Citizen Network

Dr Daniel Ozarow is Senior Lecturer at Middlesex University Business School and a town councillor in Elstree and Borehamwood

Find out more about the Local Policy Innovation Partnership Hub.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.