The Impact of COVID-19 and Brexit

Written by Pro Bono Group member and volunteer, Divya Tejwani

Introduction

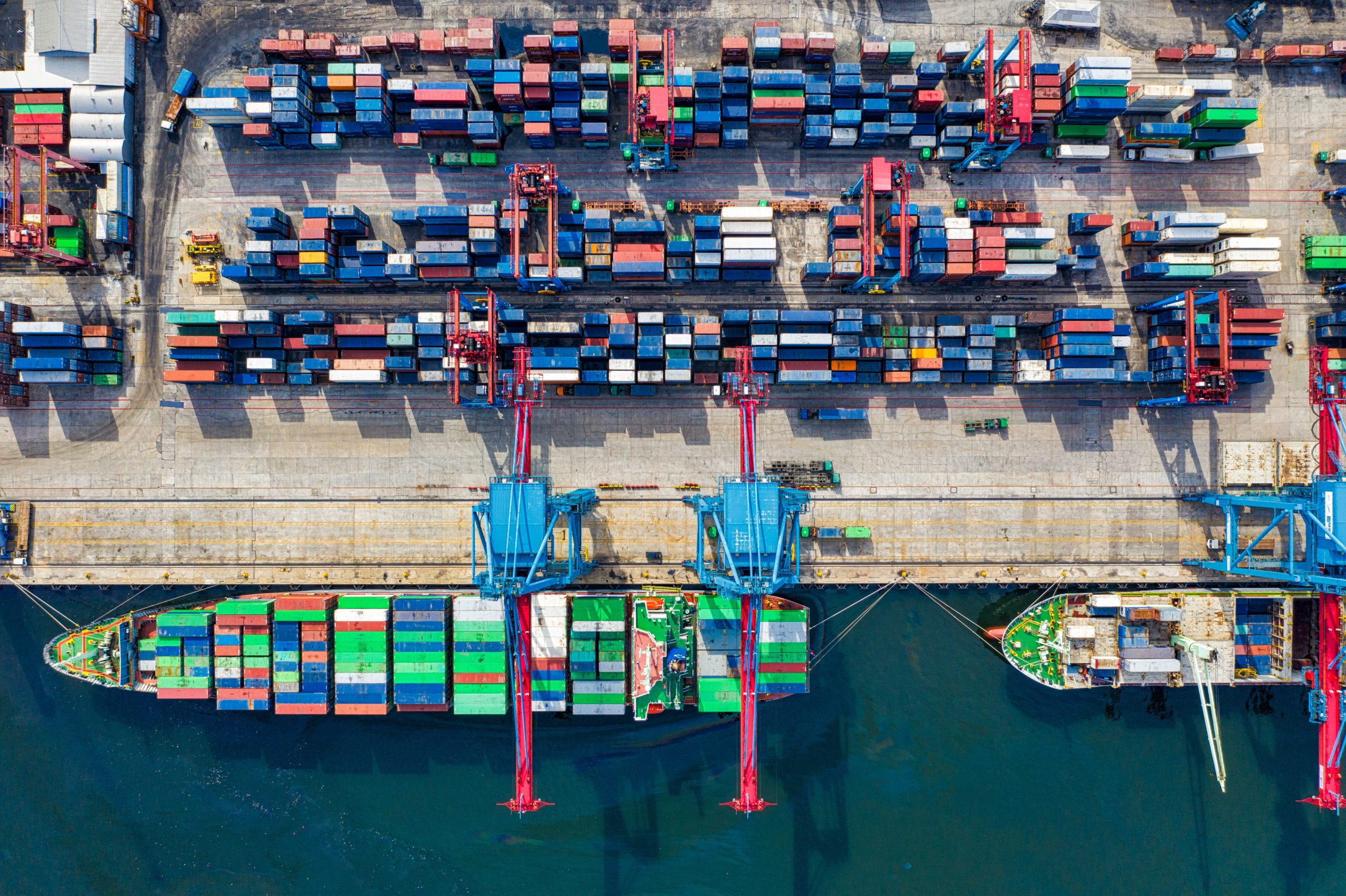

A supply chain is the process of turning raw materials into finished goods and supplying them to the end consumer of such products. Currently in the UK there is a supply chain disruption. This has been caused by food shortages and panic buying leading to empty supermarket shelves, fuel shortages, high energy prices, and general supply problems. Companies like BP,1 Ikea,2 Tesla,3 AstraZeneca4 are complaining about delays in supplies and reduced production capacity. With 17% of British population having experienced food shortages, and a further 37% of the population being unable to get fuel,5 the majority of the population in UK has been affected by supply chain disruptions. This has led to largest hikes in fuel prices, today at 159.6p/litre due to shortage of tanker drivers in the UK,6 as they returned to EU, following Brexit. Some say laden in the fog of Brexit, the UK has failed to notice the benefits it had as a member state of EU.7 While others think panic buying and COVID cases are to blame for inconveniences faced by businesses in the UK. But supply chain disruptions cannot be the result of a single factor and are expected to last beyond 2023.8

COVID-19

An ONS survey reveals that 11% businesses were unable to get goods and materials from within the UK in October 2021, having previously been at 10% in February 2021 since June 2020.9 This could be partly attributed to disruption in vocational training of lorry drivers, which took up to nine months, .10 There was already an existing shortage of 60,000 Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) drivers, even before the pandemic. This means that there were insufficient licensed drivers to replace the retiring drivers before the pandemic hit. While rising numbers of COVID cases also means higher quantity of workers self-isolating, as the number of workers self-isolating was just under 700,000 in July 2021.11 Let’s not forget too the 1.5 million EU nationals who left the UK due to COVID, many of whom were HGV drivers and have yet to return.12

There are other existing complications which can interfere with supply chains such as corporate criminal liability for money laundering and human rights breaches by employers, such as low wages and poor working conditions with drivers expected to complete long shifts, work unsociable hours and spend long periods away from home.13 . Moreover, the imbalance of power between workers and employers makes it difficult for workers to access justice and legal representations if wrongs have been committed against them in the workplace. The lower wages of employees make it difficult for them to access justice, both because the works may lack the financial power to seek adequate legal representation, and because the corporation will have finance to cover legal litigation. However, to pursue litigation, the workers need to be aware of their rights, because only then can they consider legal litigation and how to claim for such wrongs. Pro bono can help workers figure out such questions and make them aware of their rights, to be able to challenge their employers. Due to unappealing working conditions and wage competition from jobs in the distribution sector, such as in retailer warehouses, it is no surprise that workers are leaving the distribution industry14. These complications slow down the supply chain process, gradually disrupting it.

Brexit

Extensive customs checks and additional costs have led to a fall in trade across British borders post-Brexit. Paying drivers by delays in delivery of goods due to border regulations checks have made the UK a less attractive and more complicated place of employment for EU nationals who desire to be HGV drivers. In October 2021, 17% UK businesses were unable to get materials from EU,15 while 15-20% of businesses were already reporting issues in supplies from EU since February 2021. Staff shortages have worsened the problems in the supply chain, as the number of UK’s HGV drivers have fell by 37% since March 2020, where 10% of the workforce was made up of EU nationals.16 The point-based immigration system added post-Brexit means migrant workers will have to qualify for 70 points to be able to reside in the UK. These points can be gained by having a job offer for a skilled job from an approved employer and being able to speak English, which not everyone can meet, meaning even less potential workers to help upkeep the supply chain. This will also be a deterrent for the returning EU nationals, since those already residing in the UK have felt unwelcome post-Brexit and left the country.17 Due to a no-deal Brexit, the laws introduced involve additional paperwork for importing companies, a rise in transportation costs, custom duties, and a lack of logistics equipment, all of which have resulted in disruption to cross-border trading for the UK.18 This has adversely impacted the supply chains in the nation – food, drink and small businesses being the worst affected sectors.

Inflation

Where there have not been supply disruptions, there have been increases in input (production) prices. In October, inflation was running at 3.8%, above the Bank of England’s target rate of 2%.19 The governor of the Bank, Andrew Bailey, acknowledges supply chain problems are expected to slow the economic recovery from Covid. The terms of Brexit and timing of COVID have jointly resulted in supply chain disruptions and staff shortages. The resultant demand for high wages has negatively affected the confidence of business leaders during the financial year. Due to this, businesses are re-evaluating their production models. A lot of businesses are planning to shift from ’just-in-time‘ production models aimed at reducing flow times in production systems and response times from suppliers to consumers, to ’just-in-case‘ production models aiming to produce goods in advance and in excess of demand.20

Recent developments

Since Russia invaded the Ukraine at the end of last month, there has been worry about the effects of this on other countries who import resources from Russia. One third of Europe’s gas and 10% of the world’s oil supplies are sourced from Russia21. The current global conditions and continuous threats to cut oil supplies from Russia are an indicative that fuel shortages are far from over. As countries are imposing further economic sanctions on Russia with the aim of suppressing further militarization of the Ukraine, countries will have to find alternatives, which may also disrupt the supply chain. The effect of the war has already been seen in the current prices of petrol in UK petrol stations, having disrupted oil supplies22, with the price of petrol reaching a record breaking 161.1p per litre yesterday23. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is further robbing the world of its energy, impacting oil and electricity costs adversely. Although the UK is finding alternative suppliers for oil demands of the country, prolonged war will increase inflation and cost-of-living globally24, which illustrates perhaps that the end of the supply chain crisis is not yet in sight.

Measures taken by the UK Government

The government has introduced a National Economic Recovery Taskforce to improve the conditions of HGV drivers’ shortage. The Supply Chain Advisory Group, headed by Dev Lewis (Tesco CEO), aim to better the condition of supply chain disruptions in the food and beverage sector, and acts as a plaster for the recovering British economy in coming times. Changes in HGV tests to avail testing capacity, provided funding for HGV licences, and allotting temporary visas for HGV drivers from abroad25 is aiding the supply chain disruptions. Current measures such including investing in roadside facilities, relaxing cabotage or international delivery and pick-up rules, tax relief on HGV roads, exempting food workers from self-isolating rules, and maintaining energy price caps is helping the British economy recover post-Brexit at an increased pace.26 Moreover, by delaying additional restriction on imports from EU and temporarily suspending competition law for CO2 suppliers27, this has allowed CO2 producers to unite to meet the increasing CO2 demands of the fuel and beverage industry. In turn, this has helped the British economy to recover from the damage of additional supply chain disruption during pandemic and Brexit.

Conclusion

It is clear to see that there is no single answer as to what has caused the supply chain crisis. The damage caused by Brexit and COVID to the supply chains is clear, thus the British economy is frail to shoulder the consequences of Russia-Ukraine war, which could further increase prices, as we’re already seeing today. Although, the measures taken so far have had a positive effect in alleviating the pressures on the supply chain, the UK government must opt for long term solutions, and they will have to keep upgrading their strategy to predict and adapt to survive unfavourable conditions.

References

1 Richard Partington, Joanna Partridge, BP closes some petrol stations amid HGV driver shortage, The Guardian, September 24 2021

2 Joanna Partridge, Ikea owner warns of price rises as supply chain crisis takes toll, The Guardian, November 3 2021

3 Elise Leise, Tesla’s Prices Increase Due to Supply Chain Pressure, Supply Chain Digital, June 2 2021

4 Covid: What’s the problem with the EU vaccine rollout? BBC News, March 4 2021

5 Office for National Statistics, Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain: Personal experience of shortage of goods, 19 November 2021

6 Huw Thomas, Fuel Prices: Customers Abusing Forecourt Staff as Costs Soar BBC News, 9 March 20222

7 PA Media, Brexit worse for the UK economy than Covid pandemic, OBR says, The Guardian, October 28 2021

8 Peter Foster, UK supply chain crisis to last until at least 2023, business leaders warn, Financial Times, October 19 2021

9 Percentage of firms that did not respond ‘not applicable’. Office for National Statistics, Business insights and impact on the UK economy, November 4 2021

10 Road Haulage Association, Critical supply chains failing due to the significant shortage of HGV drivers, Letter to the Prime Minister, 23 June 2021

11 BBC News, Pingdemic: We got close to complete shutdown, August 16 2021

12 Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, George Eustice, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 16 November 2021

13 Mark Townsend, UK lorry drivers plan to strike over low pay and poor working conditions, The Guardian, July 24 2021

14 Ford Rojas J-P, Labour shortages blamed for surplus 70,000 pigs on farms, Sky News, August 27 2021

15 Ibid 8

16 Michael Goodier, How Brexit and Covid-19 caused the number of HGV drivers in the UK to plummet, New Statesman, September 30 2021

17 UK in a Changing Europe, EU nationals feeling unwelcome in the UK, November 28 2019

18 Institute for Government Analysis of ONS, Business Impact of Covid-19 Survey (BICS), October 3 2021

19 Office for National Statistics, Consumer price inflation, UK: October 2021, November 17 2021

20 BIMCO, Shopping market analysis, September 2021

21 Jake Horton, Ukraine War: How reliant is the world on Russia for oil and gas? BBC News, 10 March 2022

22 Petrol hits new record high of 159.6p as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupts oil supplies, The Independent, March 10 2022

23 Andy Gregory, Oil prices UK: fuel costs hit yet another all-time high as ministers urged to cut VAT for drivers, The Independent, March 11 2022

24 Rob Davies, How important is Russian oil and how high would proves go? The Guardian, 7 March 2022

25 Gov.UK, UK government action to reduce the HGV driver shortage, accessed 11 November 2021

26 Cabinet Office, Government sets out pragmatic new timetable for introducing border controls, Press release, Cabinet Office, 14 September 2021

27 BEIS, Further support to ensure supplies of Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Press release, 1 October 2021