Over the summer of 2017, I worked on the project Women’s Legal Landmarks (WLL). WLL was fun, insightful and an amazing project to work on and be part of! Not only did I research important legal landmarks, but I also learned about the women and campaigns that fostered the change in the law, and how they are perceived.

WLL is a collaboration of feminist scholars who identified over 90 landmarks. These landmarks have contributed to the legal advancement of women across the UK and Ireland. It is a commemorative project marking 100 years since the enactment of the Sex (Disqualification) Removal Act 1919, that allowed women to practice law. The landmarks begin in 950 AD, with the Laws of Hywel Dda, and continue to 2017, with Lady Hale as the first woman President of the Supreme Court. While working on the WLL project, I was asked to research publicly accessible documents that could complement and provide more information for the summaries of the landmarks that were shared on the website.

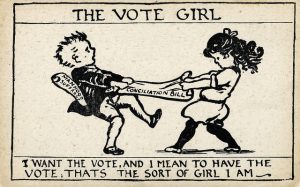

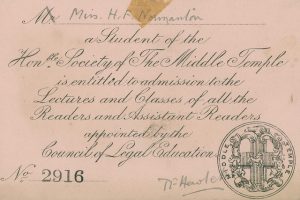

There were a few things that I found interesting while researching the landmarks. First, information on the ‘first women’, i.e. the female barristers, solicitors and judges, varied significantly. Certain woman barristers, for example, were known for their achievements, and had more written about them, than other female barristers who made similar advancements for women during the same time. Second, like the ‘first women’ landmarks, the accessibility, quality and quantity of images and portraits varied significantly. When putting together a website, an image (photo, drawing, painting) of a campaign, building, or person that readers can have a tangible link to is imperative. This is important now as more and more people have various electronic devices. Online articles, posts and blogs, rarely come without a headline and relevant images. In addition, without an identifiable marker there is difficulty in understanding and contextualising the person or event. Indeed, it is why there are portraits, depictions of wars in paintings, and statues to commemorate important events and landmarks. The third, and final, aspect I found interesting was the quality and quantity of publicly accessible documents for the landmarks. Much like the ‘first women’, what was available and accessible from primary to secondary documents was uneven. Some events, like the right of women to be served at a bar (Gill and Another v El Vino [1983]) were widely reported and photographed, while others – particularly involving property and ownership – were not.

However, more often than not, the biggest difficulty that transpired in obtaining publicly accessible documents, was that the landmarks appeared to be insignificant. ‘Landmarking’ these events, unknown or forgotten, was a core motivation for WLL. Once the landmark is understood, its significance and impact cannot be ignored. Examples of this include: Williams and Glyn’s Bank v Boland [1981] where a woman’s legal interest in the home was recognised and can be an overriding factor; the UK’s first feminist law journal, the creation of the Feminist Legal Studies journal in the 1990s was the first step, which validated and fostered feminist critical legal thought; Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon who, in the 1880s, poignantly outlined the legal position English women faced in a pamphlet, and, alongside with other women, laid the groundwork that would give rise to the modern feminist movement. The superficial insignificance meant that information was found on niche blogs, websites, or, occasionally, reported in a newspaper with an analysis on the historical event.

Over my five weeks of research I have begun to think differently in my approach to academic research. Since I had to limit my resources to articles, blogs, websites and online journals that are publicly accessible, I learned that while a quick Google search may throw up many historical sources, legitimate and accurate sources can take time to find. I also learned that information beyond academia disappears. Easy access to academic journals, books, and archives is a privilege, and I am fortunate that my learning is not dependent on a limited number of internet sources. In addition, the five-week focus on a single research project has given me insight as to what it would be like to work on a degree that is reliant, almost entirely, on my own research.

Laura-Anne Goulding, LLB Law