This is a guest blog post written by Nick Leonard, the Estoria project’s most active crowdsourcer and friend of the project.

My interaction with two Estoria de Espanna manuscripts over the past 18 months, while enthralling in its own right, has largely taken the form of looking at lines of text through a digital magnifying glass. In order to transcribe and tag the folios, it is necessary to zoom in to the point where I see the manuscripts as little more than lines of code. It’s beautiful code, of course – despite somehow managing to contain almost as much gobbledygook as modern computer code – but it’s code nevertheless. I rarely see more than three lines of text at any one time, and I almost never consider the manuscripts as objects beyond the text that I’m working with.

Seeking a different perspective on the Estoria, I recently went to the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. With the aid of the EDIT project team, I gained access to the 14th-century Q manuscript and could hold in my hands the very same book that I had spent hours tagging in 2014-15 on a remote computer screen.

Finally, the code had become a codex.

My first surprise when the manuscript was brought to me was how large it was. In my world, Estoria manuscripts are only as big as the top half of an 11.6-inch laptop screen. But in the Sala de Cervantes, I was handed a manuscript over a foot high and nearly three inches thick. Even at only 186 pages, its girth dwarfed the 600-page modern hardcover book I had brought with me to Madrid. Despite the lack of cover decoration, this impressive size conveyed a sense of importance all on its own, and reminded me that what I was about to open was no ordinary library book.

The large but fairly ordinary cover of Q does not betray the fabulous story that unfolds inside: thousands of years of Spanish history from pre-Roman times to the Late Middle Ages.

The large but fairly ordinary cover of Q does not betray the fabulous story that unfolds inside: thousands of years of Spanish history from pre-Roman times to the Late Middle Ages.

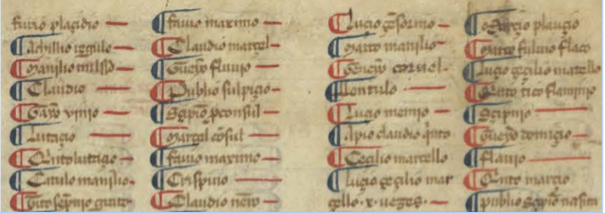

Image: Biblioteca Nacional de España, MSS/7595, p.1.

After opening the old leather binding, I spent the best part of my morning slowly turning every creaking page of the 600-year-old manuscript, spellbound by this completely new experience of an object I had thought I knew well. The pages alternated in colour and texture (the flesh side of the parchment being smoother and lighter than the hair side), something that had completely escaped me while using the digital edition and working on only one folio at a time. The pricking and ruling on each page – more obvious on some pages than on others – was another thing that I had never noticed before because I was so focused on the text itself.

Following the ruled lines led me to the margins, which I had barely considered while transcribing Q on a computer screen. Some folios contained catchwords to make it easier to form quires after writing. Others contained notes in the side margins. One folio near the beginning (3r) even had the alphabet written out in the lower margin, which was perhaps the Q scribe’s way of helping future Estoria transcribers distinguish his letterforms (although I’m still looking for his guide to abbreviations…).

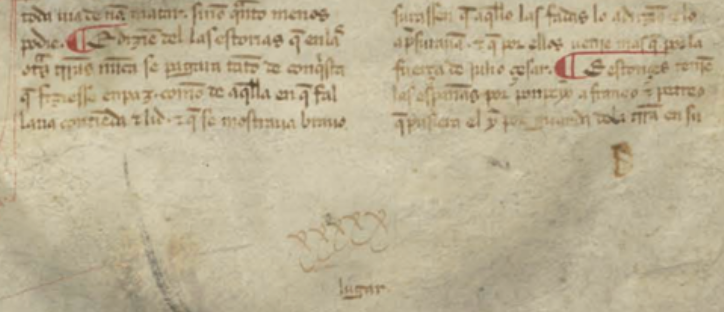

Folio 50v of Q. In the lower margin, the catchword ‘lugar’ is written. This is also the first word of the next folio, 51r. Adding catchwords to a folio made it easier to join individual folios together into gatherings or quires which would then be bound together to form a manuscript.

Image: Biblioteca Nacional de España, MSS/7595, p.55.

Once I had adjusted to this new, wide-angled view of Q, even the text itself delivered a few surprises. I found one page (57v) that had 44 coloured pilcrows contained within the text of just the first column alone. A few folios later (65v), even more pilcrows popped up, this time serving as medieval bullet points. Some initial capital letters, typically uniformly conservative throughout Q, had extra grandeur bestowed upon them, such as the P on folio 72r which is more than half the page in length. I also realised that many (but not all) of the rubrics begin with the phrase ‘De como’, another thing I had never noticed before while working on one folio at a time.

Folio 65v of Q. Alternating red and blue pilcrows function as medieval bullet points.

Folio 65v of Q. Alternating red and blue pilcrows function as medieval bullet points.

Image: Biblioteca Nacional de España, MSS/7595, p.70.

Seeing an Estoria manuscript in person gave me a new understanding of the physical objects that are at the core of the EDIT project. With this fresh perspective in mind, it’s time to go back to my lines of code on a computer screen. But from now on, I will remember to zoom out and take a look around every once in a while to see what new discoveries are waiting to be made.

1 thought on “Guest Blog Post: Up Close and Personal with the Estoria de Espanna in Madrid”