According to the list of sources for each chapter of the Estoria which appears in the Menéndez Pidal edition of the text in 1955, when the Alfonsine compilers were putting together the chapter entitled “Del imperio de Trajano ell emperador e luego de lo que contescio en el primero anno del su regnado” (“Of the empire of the emperor Trajan and then of what occurred in the first year of his reign”), they based themselves above all on Vincent de Beauvais’ famous Speculum historiale. The fragment that appears here in Transcribe Estoria is the first part of that chapter and it is dedicated to illustrating some features of the exemplary character of Trajan and the wisdom he acquired from his maestro Plutarch. This is done primarily through two short anecdotes. We have here, therefore, in a few short lines, something of a “mirror of princes”.

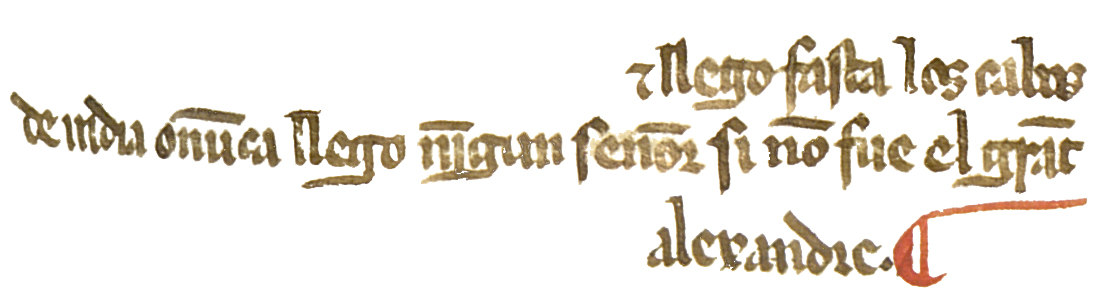

Trajan, who is said to be from “a town in Extremadura called Pedraza”, is described to us as “muy franque” (that is, liberal and generous) with his friends; we are told that he lowered or eliminated taxes on the cities which were being suffocated by them; and he was mild in his dealings with the citizens and he restored the previously damaged state of Rome. In military matters, the Estoria tells us that he conquered vast lands beyond the Rhine, the Danube, the Euphrates and the Tigris (You might like to note that our manuscript reads “Tibre”, that is the River Tiber here. This is an error for “Tigre”, the River Tigris, which is what it should read). Trajan is then recorded as reaching further than any lord in his conquests “with the exception of Alexander the Great”.

In the first of these two anecdotes, we are introduced to two other virtues of Trajan: his compassion and justice. A widow appears before the Emperor, who is on horseback, and demands justice of “two men who wrongly killed her son”. When Trajan promises her that he will deal soon with her petition, she insists that he do so straight away “since it is you who is my debtor” and “you will deceive if you do not give me my due”. Trajan, on hearing this, is moved, takes pity on her and does as she asks. This decisive woman is one of many we encounter in the two Alfonsine histories -the Estoria de Espanna and the General Estoria– who complain of wrongs done to them and demand justice as a result; other examples include Rhea Silvia, or Ilia, the mother of Romulus and Remus when she is condemned to death by her uncle, or Hypermnestra, the only one of Danaus’ fifty daughters who refuses to kill her husband.

The parallels with past virtue continue here: just as Alexander the Great had Aristotle as his guide and maestro, so Trajan has “another philosopher”: Plutarch. In the tale of Plutarch which is recounted here, we see two more virtues of a lord, of a powerful man, which were understood as such in the Middle Ages, although they are perhaps harder to understand in the contemporary world.

Plutarch orders that a servant of his be thrashed with some reins. The servant reproaches him for acting contrary to his own philosophy, for Plutarch has written often of the “evil that comes from ire”, and the servant tells him that “you have allowed the understanding of your heart to contract and you have been overtaken by anger”. But Plutarch responds to him that, on the contrary he is not “angry”, overcome by ire, for, he asks rhetorically, “can you see anger in my face, my voice, the colour of my cheeks or in my words?”. No indeed, for “my eyes are not wild, my face is not twisted, I am not shouting without control, I am not sputtering, I am not saying shameful things nor anything of which to repent, nor am I shaking with anger”. Rather, what Plutarch is saying (a point picked up in turn by Vincent de Beauvais and Alfonso’s Estoria) is that he is punishing “the rebellion of the servant, so that the wrongdoer should repent for what he had done”.

And, of course, anger, as the absence of measure and the loss of self-control is a negative characteristic for any lord. Rather, the lord, given his role in society, should punish the wrongdoer while occasionally revealing the ira regis, which is precisely what Plutarch does with his servant. The same principle is already outlined in Biblical texts which declare, in the version transmitted in the General Estoria: “Anger is better than laughter, for sadness in the face punishes and emends the heart of the sinner” (GE, Third Part).

The Estoria, as is almost always the case, thus offers us not just what happened, or could happen, at any determined moment or place, but also gives us histories, personalities, models of behaviour and societal frameworks which are destined to resonate far beyond this “first year of the reign of Trajan”.

Belén Almeida

Biography

Belén Almeida is a Spanish language lecturer at the University of Alcalá. She completed her doctoral thesis on the Fifth Part of the General Estoria of Alfonso X the Wise. She has researched and published works on the General Estoria, translation in the Middle Ages and language and writing in manuscripts up to the 19th century. Profile in Academia and UAH.