Congratulations! When we looked through your transcriptions of Text 3, we could see that the general tendency towards a greater precision in reading and transcribing the manuscript that we commented on in Text 2 had become even more marked. It’s clear that you are all gaining in confidence and that it takes you less time and effort to arrive at appropriate solutions when you are altering the base text. And it is also clear that you are getting much more accustomed to the hand of the manuscript (the Gothic book hand we mentioned previously) and, more importantly, the usus scribendi with regard to letter forms and abbreviations. This is very important, because it means you are all overcoming the “base text effect” (that is, we all know we have to correct the base text, but its mere presence makes us doubt our own judgement) and getting more confident in your readings of the manuscript. So all of those graphical differences between E1 and C that confused many of you at the outset, no longer cause you such trouble.

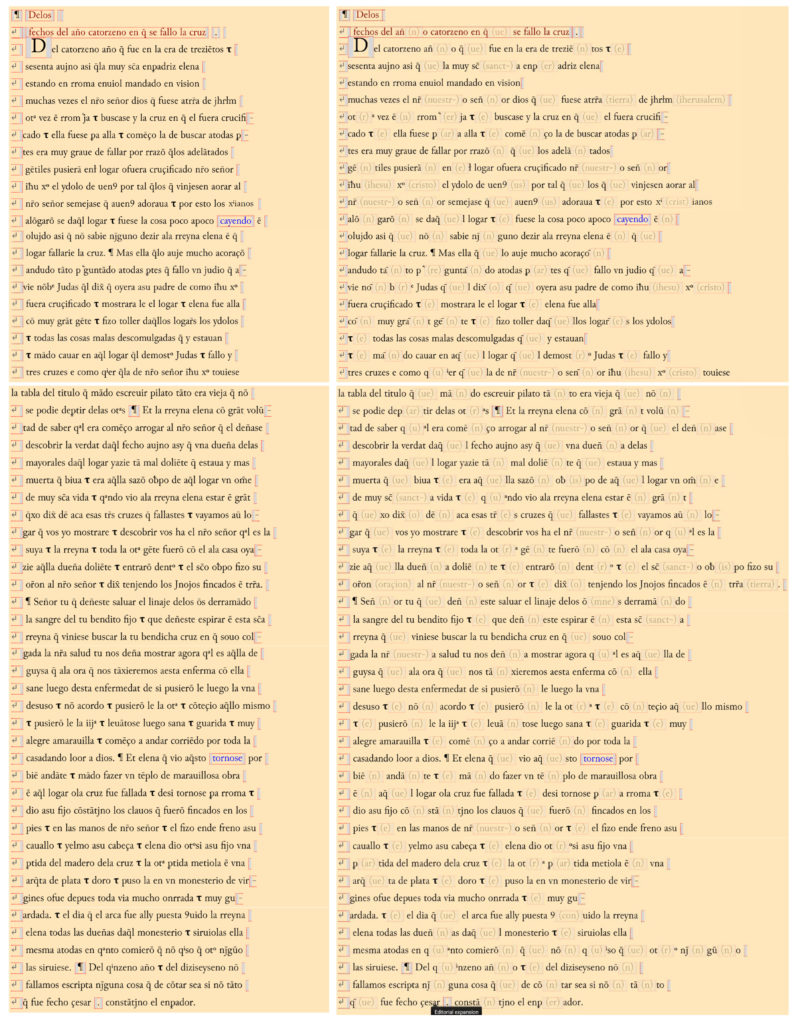

Here you have the transcription capture in the system (with and without expansion of abbreviations):

For example, we are no longer really finding any errors with the expansion of the macron with nasal value. If you recall, in Text 2, and especially in Text 1, we found many examples of (e.g.) “i(m)perio” or “e(m)perador” with an <m>, when in fact the usus scribendi tells us that it is more correct to find <n> in this context – thus “inperio”, “enperador”. In Text 3 we found relatively few examples of “te(m)plo” or “no(m)bre”, instead of “te(n)plo” or “no(n)bre”. There were a few, but very few. Similarly, in your transcriptions we found few examples of <ñ> (following current orthographic norms) of <nn> without abbreviation, though we did come across a few examples such as: *señor > sen(n)or, *dueña > duen(n)a, *dennasse > den(n)ase.

You might also want to take a closer look at the final example. The double consonant <ss> in E1 (dennasse) appears as a single <s> (dennase) in C. This is very important at the graphic/linguistic level, because it probably indicates the loss of the voiced/unvoiced distinction in written texts from the end of the 13th century onwards. You can see this in other words in C also: *buscasse > buscase, *semejasse > semejase, *dizisesseno > diziseyseno, etc. So be careful with the <ss>! It usually appears in the base text, but the equivalent in C is generally (though not systematically) a single <s>.

In your transcriptions we have also seen a significant decrease in the confusion between <v> and <u> in word initial position. Remember that you almost always have to correct <u->, which is the way it appears in E1, to <v->, which is typical of C. Here are a few examples we picked up upon in Text 3: *uision > vision, *uezes > vezes, *uez > vez, *uieja > vieja. However, one feature where we still see some errors in the transcriptions (albeit rather less than previously) is in the distinction between <i>, <j> y <J>: *iudio > judio, *viniesen > vinjesen, *nin > njn, *auino > aujno, *guarida > guarjda, *constantino > constantjno. Remember that when the <j> has a high stroke (<J>) we only acknowledge this in word initial position, whether or not this corresponds to the current use of capital letters (e.g. *judas > Judas, *inojos > Jnojos). Please don’t think, however, that all the errors are yours! Nothing could be further from the truth! As the project proceeds, we are also finding out the limits and limitations of our transcription platform (in passing, your comments help us greatly in developping the transcription desk for the future). As Aengus pointed out in a recent post (Lessons learned…), the precision we ask for in distinguishing between certain spellings (<i, j> for example) is not always matched by the capabilities of the system – especially where abbreviations are concerned. For example: what are you supposed to do when, as in Text 3, the abbreviations <ihrlm> (Jerusalén) and <ihu> (Jesu-Cristo) appear with an initial <j>? This is a very good question, and several of you have commented on this very issue to us. For the moment, and mainly to avoid overloading the palette of characters in the abbreviations menu, we will leave the abbreviation as it is, with an <i>. But we have taken note of this so that we can correct it in future manifestations of TranscribeEstoria.

Errors which are now very infrequent are confusion between upper- and lower-case letters (*mas > Mas), or confusion in the choice of abbreviation in the list of special characters (*q(r) ͥ er > q(u) ͥ er). This confirms the previous evidence that you are all getting used to the system and to the differences between different forms of abbreviation. However, there are still a few things you might like to note, both in terms of phenomena that have come up for the first time in Text 3 and also one-off errors Ricardo has picked up in your transcriptions:

-

-

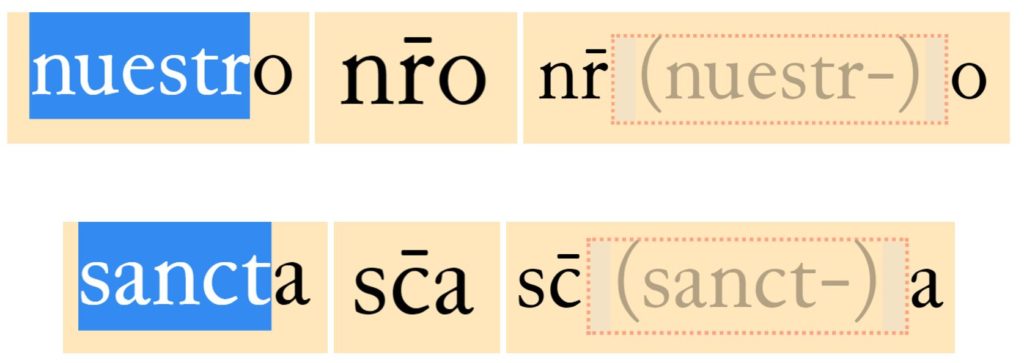

- Abbreviations NUESTR- and SANCT-: take care when entering these abbreviations, because, as you can see, they do not include the end of the word in question (e.g. morphemes indicating number or gender: nuestr-O/A/OS/AS, sanct-O/A/OS/AS). We present these abbreviations in this way so as not to have up to 8 different variants of the same abbreviation, that is, one for each possible realisation. When you use these, make sure you select the right length of sequence from the base text:

-

-

-

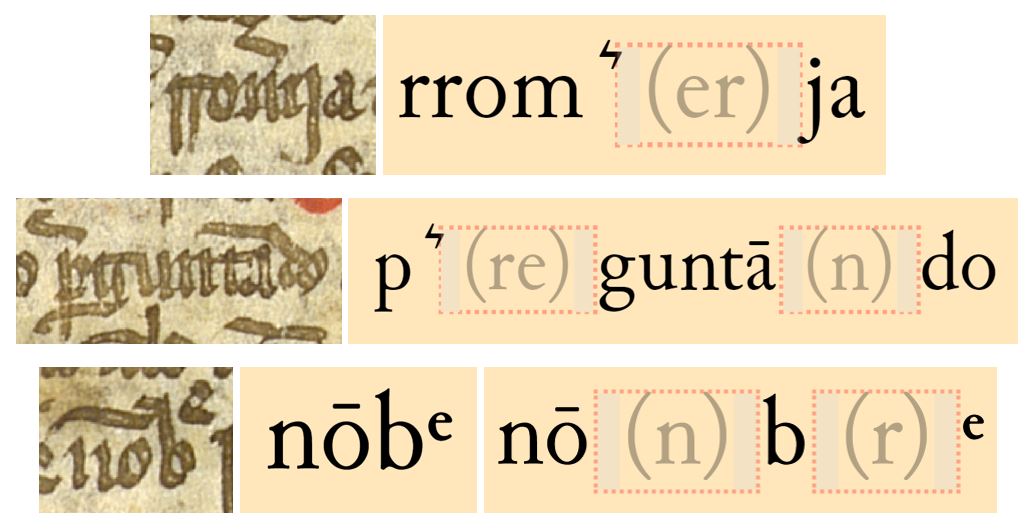

- ER and RE: This is probably the abbreviation context that has caused the greatest range of confusion, because they are often poorly distinguished in the manuscript and they are easy to confuse with the superscript <e>. These two examples are the ones where we found the greatest level of confusion: the noun “rom(er)ja” and the verb “p(re)guntando”. In the first case, some of you forgot to indicate the abbreviations (the ‘superscript hook’, in the 4th line of the palette, 2nd character along). In the second case, a few of you interpreted the mark as a superscript <e>, when in fact it is the same mark as the previous one (albeit it represents <re> and not <er> in this case). For comparison, here is a true case of the superscript <e>, in the word “nonb(r)ᵉ”.

-

-

-

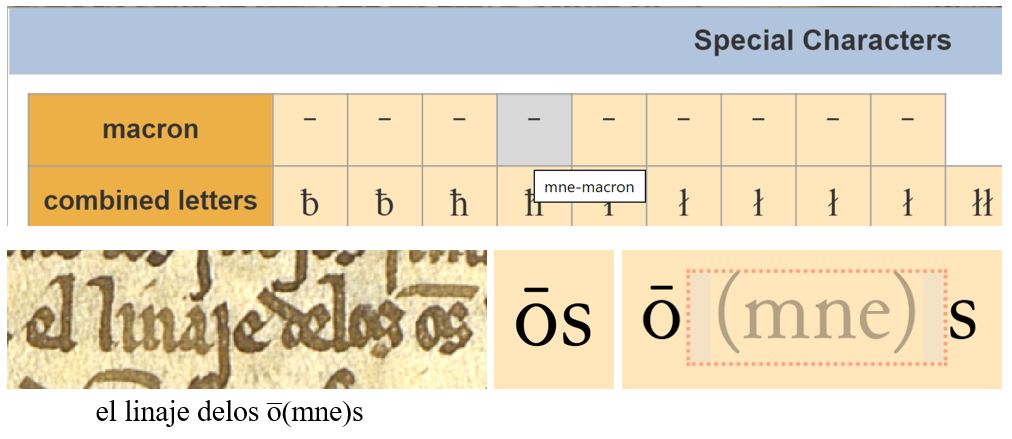

- Abbreviation OS > o(mne)s: thanks to all of you who pointed out the absence of this one to us. It’s now in the first line of the palette, fourth character along.

-

-

-

- Macron with the value of O or E: *dixo > dix̅(o), *logares > logar̅(e)s. Remember that you can find these little-used abbreviations in the special characters menu palette, first line towards the end.

- Symbol US: *uenus > uen9(us). This symbol looks like the number 9 and has the value of <us> or <con> (e.g. confirmar). It’s on the fourth line of the palette, towards the end, just before the <ç> cedilla.

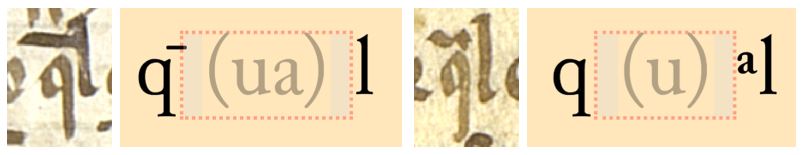

- Macron with the value of <ua> vs. superscript vowel <a>: it is very easy to confuse these two, especially when the value of the expansion is the same, that is, <ua>. In Text 2 we saw a few examples of “qual” abbreviated with a macron: q̄(ua)l (“qual conuenie”). Reasonably enough, a few of you thought that this was the sequence “quel” (q+ macron = <que> + definite article el or the pronoun le apocopated), but in fact it is the sequence <ua> abbreviated with a macron, which does appear albeit with less frequently. This means it helps to be quite attentive to the context and content of the text to be able to interpret the meaning correctly. If your Spanish is not so good, you can always ask us! In any case, in Text 3, it is more common to find the sequence <ua> abbreviated by a superscript <a> than by a macron, thus: q(u)ªl. Here are the two for you to compare:

-

-

-

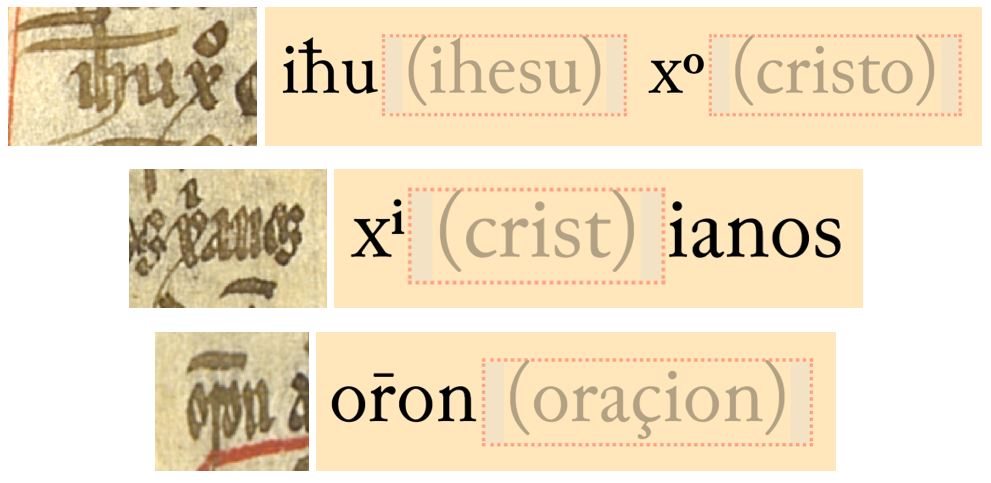

- Abbreviation of CRISTO, CRIST-, ORAÇION: you already know that the abbreviations menu has two options for the abbreviating ‘cristo’: xp̅o and xº. In Text 3, you will have spotted that the second of these, (xº) is the one to use. As far as the form “cristianos” is concerned, we have included amongst the special characters in the abbreviations menu the option <x ͥ >, which represents the sequence “crist-“. But this means that you have to include the <i> additionally in your transcription. Note that this is different to when superscript <i> abbreviates <u> or <r> in, say : q(u) ͥso, or p(r) ͥmero, as the expansion in your transcription already includes the <i>. And finally, in the second part of Text 3, we can see the abbreviation “or̅on“. But we guess you all know what this means…!

-

-

-

- Other transcription errors we have found: *benedito > bendito, *uj tercera > iijª (you can type the ª directly from your keyboard) *cruçifigado > cruçificado, *fazon > sazon (confusion between high <s> and <f>), *razon > rrazon (in C it is most common that initial <r> is doubled), *ell > el, *alli > ally, *misma > mesma, *dizisesseno > diziseyseno.

-

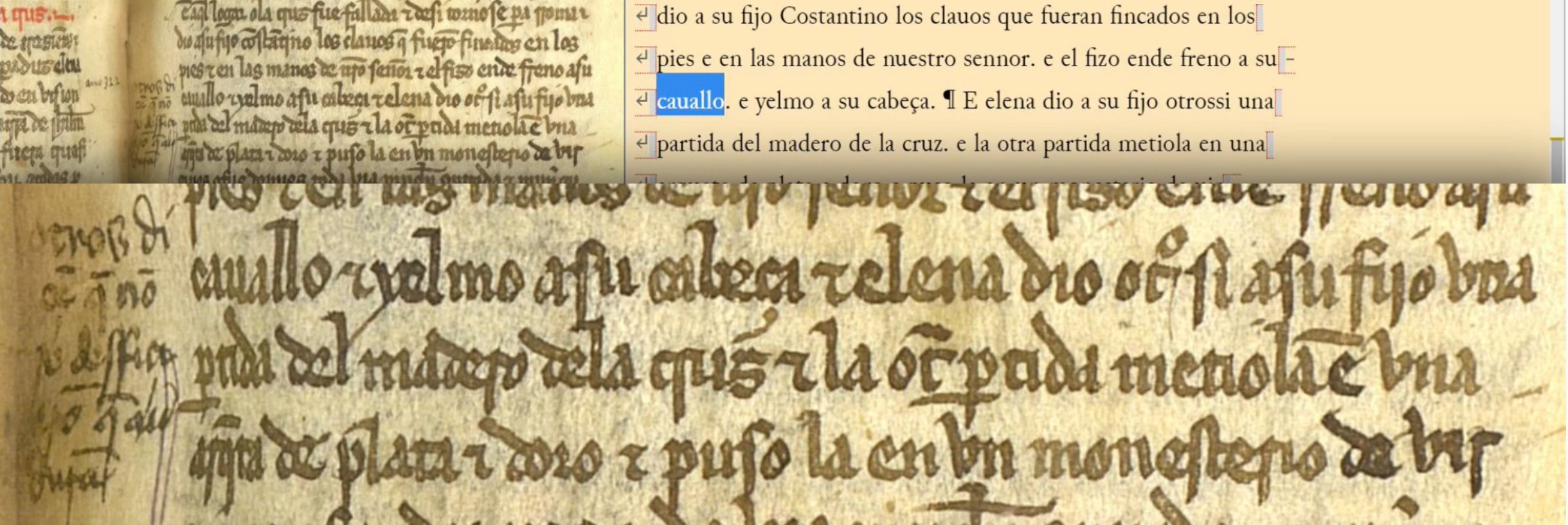

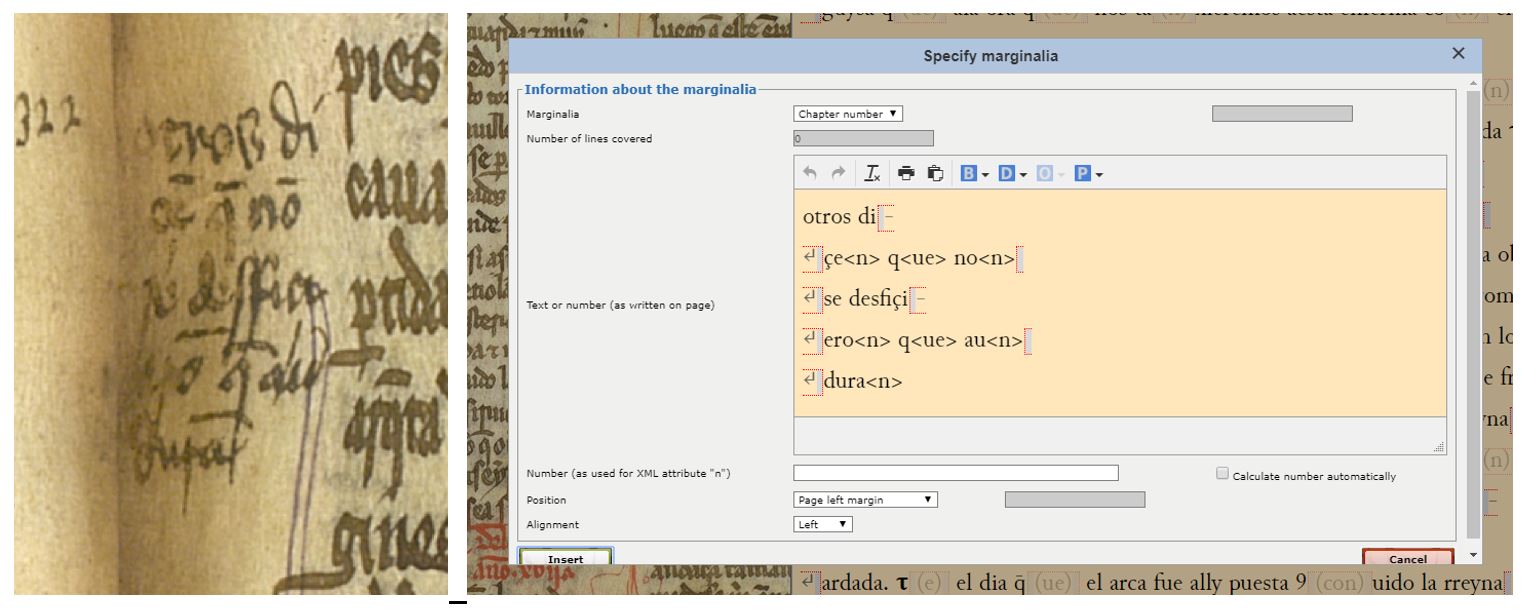

We’ll round up this review of the transcriptions of Text 3 with a reminder how to tag marginalia and other corrections by the copyist/reader. With regard to the former, we put up a note on our social media a few days back on how to interpret marginal notes and how to tag them. The correct reading of the note in question is: “Otros diçen que non se desfiçieron; que aun dura/Others say that they were not taken apart; that it is still intact”. This is a reference to the passage we were transcribing, about how Helena divided the wood of the True Cross in two parts, giving one to her son and another to be kept in a monastery in a gold and silver ark). Whoever wrote the note is telling us that in other sources (“otros”), it is said that the wood was never split, and that it is preserved intact. To transcribe this note, you have to use the Marginalia menu (you have to place the cursor in the text just before the word “cauallo” at the beginning of line 27 of the column in question, just where the note begins in the margin). It is a vagary of the system for now that we cannot use abbreviations in the Marginalia menu, so we have included them between angle braces (< >), but you don’t have to do this in your own transcriptions.

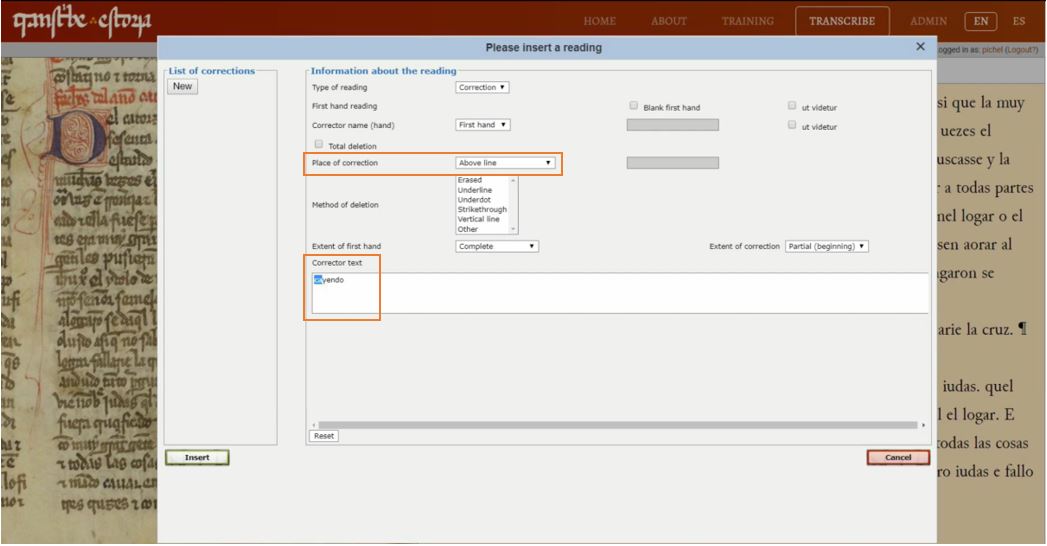

Similarly, in Text 3 we can also see two further corrections by the copyist or reviser. We commented on these in the fourth training module in the Training section, but we’ll recap here as well. In the first fragment, you can see that in the word “cayendo” the first syllable has been added in the interlineal space. We mark this using the Correction menu. as we mentioned before, you only have to fill in two of the fields: ‘place of correction’, in this case ‘above line’; and the text of the correction (in the box ‘corrector text’). As you can see below, you just have to write the corrected word (“cayendo”) for the system to record the appropriate information.

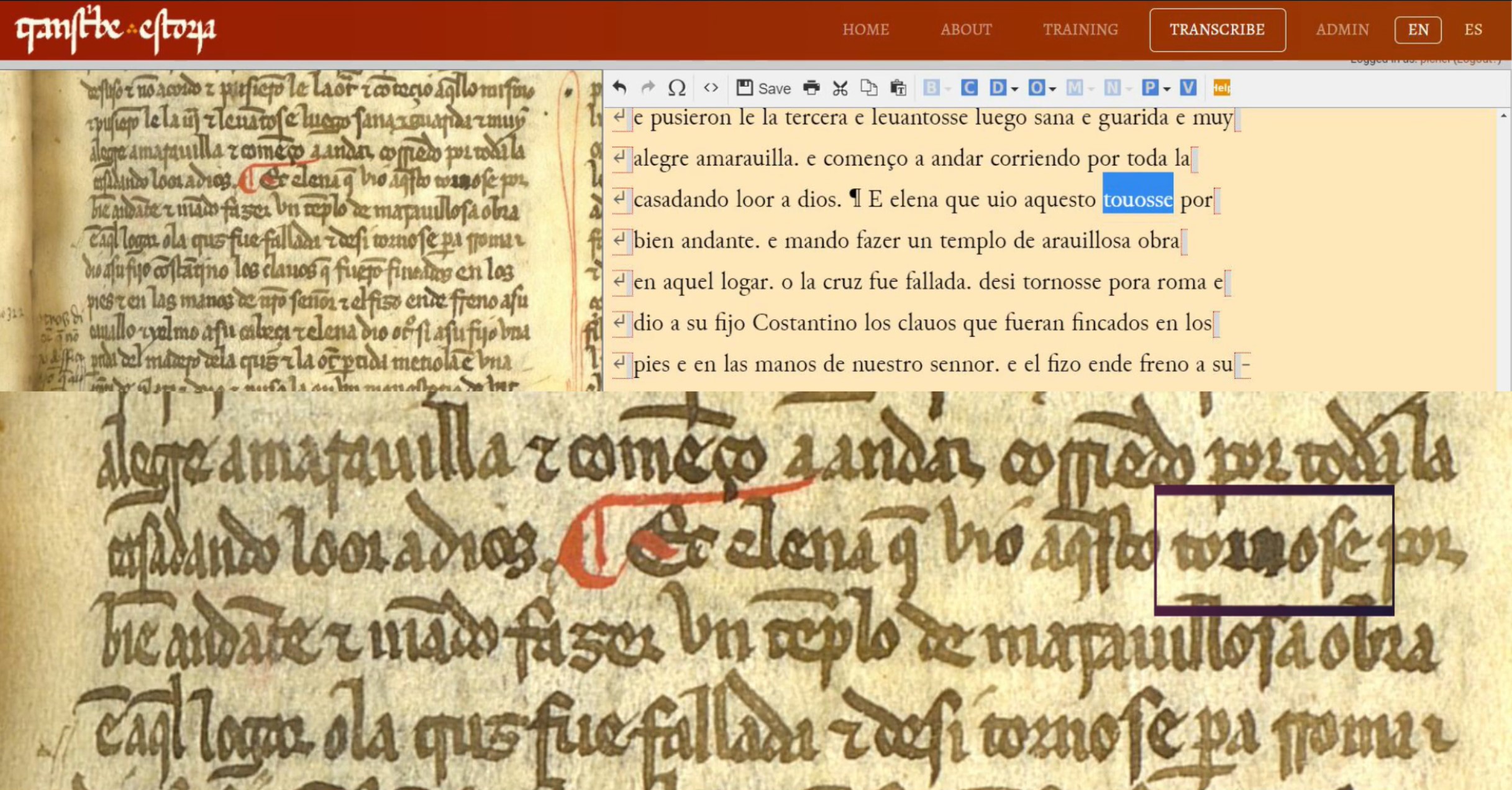

In the second part of Text 3, we can see another correction – in the word “tornose”, in which some alteration has been made to the letters <r> and <n>. This is quite possible, for if you look at the base text you can see the word “touosse” (‘se tuvo por bienandante, se sintió afortunada/he felt fortunate’). It is likely, then, that the scribe noticed the error and tried to emend the sequence <rn>, replacing it with an <u>: “tornose” > “touose”. Whatever the truth of this, we have to indicate the correction in the Correction menu again, this time indicating both the incorrect and the corrected form. You can also indicate where and how the correction was made (in this case we choose ‘overwritten text’).

That’s all for today! We hope this post has been useful and interesting for you. We’ll be back in the next few days, so don’t miss new entries in the blog, with news of Text 4 and other matters. Let us know here, or in social media, of how you are getting along. We are always ready to lend a hand!

Ricardo, Polly and Aengus.