Transcribe Estoria should have been represented at the Leeds IMC this week, but unfortunately the realities of teaching remotely whilst home-schooling two small children meant that I was not able to go ahead with the digital conference. I suppose that makes me a statistic. The paper I had proposed was going to be entitled ‘Crowdsourcing the Estoria de Espanna: pedagogical considerations for a crowdsourced transcription project’.

Whilst a blogpost is not a conference paper, I recognise that there is a small, niche audience for whom this topic would have been interesting, and by coincidence I was contacted by someone asking about the methodology within our crowdsourcer training on Wednesday, the very day that I should have been speaking at Leeds. For this reason, I would like to give a whistle-stop tour of some of the highlights, if they can be called that.

Whilst researching and setting up, and later reflecting on the crowdsourcer training for the original Estoria de Espanna Digital project, it was immediately clear that the approach a transcription project takes towards training its volunteer transcribers is very closely linked to the nature of the project itself, the content of the manuscripts being transcribed, and the level of transcription detail required by the project for any volunteer-produced transcriptions to be useful for the project. In my PhD thesis (if you want to read it, email me) I talked about how a project requiring full XML of texts in an ancient language would appeal to a very different audience to those to whom a project involving the transcription of more modern texts into bare text would appeal. And of course, these very different audiences would need training in a very different way. To give just two examples of how: their starting points would differ, as would the skills transcribers would need to acquire to enable them to carry out the transcription task to an appropriate level of accuracy.

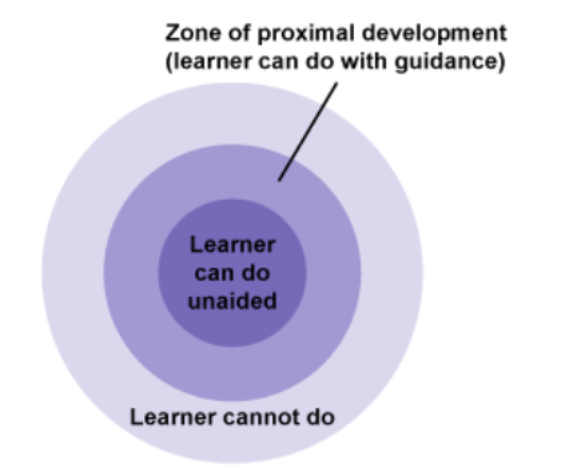

Also relevant to the training crowdsourcers receive is the feedback a project provides them with, which again can come in many different ways and with different levels of detail. Although this is part of the retention of crowdsourcers, it is also crucial to their ongoing training. In order to stay motivated to continue transcribing, volunteers need to feel that they are gaining something from the task. This is a ‘what’s-in-it-for-me factor’. In paid employment what’s in it for the worker is monetary gain. In unpaid-volunteer transcription projects this gain is generally not financial, but rather it is a personal gain – for some this will be educational, for others it may be religious, depending on the nature of the texts being transcribed, or a feeling that they are genuinely contributing to scholarship. The perceived gain to crowdsourcers by taking part in a transcription project will be as wide and varied as the volunteers themselves, and will vary from individual to individual. In projects such as the Estoria Digital and Transcribe Estoria, where many volunteers are transcribing to fulfil a learning need, or to satisfy their cognitive surplus, they need to perceive that they are continuing to learn. The task needs to become more difficult as they improve, but should remain do-able, and not too daunting. In education we use the concept originally conceived by Lev Vygotsky called the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

Image reproduced from https://www.open.edu/openlearn/languages/understanding-language-and-learning/content-section-6 [accessed 10/7/2020]

In order for the transcriber to continue to perceive the task to be worthwhile when the primary pay-off is an educational gain, the task required of a transcriber should be within their ZPD. When they improve, which they will do with practice and careful feedback, the task required of them should be made marginally more difficult, to move the task back to the transcriber’s ZPD or risk them losing motivation and no longer taking part in the project.

The original Estoria Digital project required transcribers to edit an existing bare base text transcription to match another witness, transcribing to a high level of detail, and using and adapting a series of XML tags to represent the abbreviations in the new witness. Before a volunteer could start transcribing they had to download and install Junicode and edit their advanced settings in Chrome. If this was too far outside the potential volunteer’s ZPD, even this first hurdle was so technical that it would be immediately off-putting, and it probably did affect how many crowdsourcers joined our project. The training for the Estoria Digital transcribers was a course on Canvas, the virtual learning environment used by the University of Birmingham. The course contained a series of modules that a volunteer would move through at their own pace, and in their choice of language, English or Spanish so that as many users as possible could learn in their native language. Each module started with clear learning outcomes that learners could use to self-assess at the end of the module to check their own learning. Following this, the content for that module was presented over a series of pages, illustrated by images, screenshots and screencasts of transcription in action. The content within each module was divided into smaller portions using chunking to reduce the risk of cognitive overload. Content was delivered step-by-step using clear sentences with any technical terms explained, lest they be seen as jargon. At the end of each module was a short quiz designed to check a learner’s progress against the learning outcomes. The content of the course ranged from the simplest tagging, that is, line-breaking and adding in hyphen tags, to complex transcription such as encoding split rubrics with a number of segment IDs required. The course itself depended on a high level of motivation from the would-be volunteer transcriber, but the high level of detail required and the difficult task of editing and XML tagging a bare base text transcription also required a high level of motivation from the transcriber.

Having successfully completed the course, a volunteer would be assigned a folio to transcribe, starting with line-breaking and working up to full transcription, supported one-to-one by members of the Estoria team. Inspired by Vygotsky’s ZPD is Jerome Bruner’s notion of instructional scaffolding, where a more knowledgeable person provides support to a learner until the learner can carry out the task independently. In the Estoria Digital project this scaffolding took place in this one-to-one feedback to volunteers by members of the team, who would look over and correct the transcription produced by a volunteer, diagnostically analyse misunderstandings or gaps in the volunteer’s knowledge and provide individual feedback to plug these gaps. Where appropriate, they could then gradually increase the level of difficulty of the task a transcriber was carrying out, moving from line-breaking right through to full XML tagging. This system was extremely laborious but successful with the small numbers of crowdsourcers we had, with around fifty crowdsourcers, of whom seven could be described as regularly active, and in one case enabled a volunteer to move over the course of a number of months from line-breaking to tagging extremely complex <app> tags to show scribal emendation. The system would, however, have been unworkable with a much larger number of volunteers.

Whilst crowdsourcing made up a small part of the Estoria Digital, it was the basis of Transcribe Estoria, as a public participation project, the pilot project of which ran from September to December 2019. In Transcribe Estoria we anticipated and achieved far more crowdsourcers than with the Estoria Digital, with around 200 transcribers saving at least one transcription, and 18 saving all five. The training for Transcribe Estoria was informed by our experiences when training crowdsourcers for the Estoria Digital, but differed in a number of ways because of the differing natures of the task involved and of the project itself.

Transcribe Estoria still required volunteers to transcribe a bare base text, but without the requirement to first download Junicode or edit settings in Chrome. Neither did volunteers have to edit strings of XML tags, as Transcribe Estoria used a what-you-see-is-what-you-get (WYSIWYG) tagging system, since as only one manuscript was being transcribed in this pilot project, the tags would not generally need to be edited to represent the usus scribendi of that manuscript: the tags were created with the usus scribendi of that manuscript in mind. This meant that the level of difficulty of crowdsourcing for Transcribe Estoria was lower than that of crowdsourcing for the Estoria Digital, and therefore widened the potential audience of transcribers, as well as the numbers of transcribers we achieved. This is not to say that transcribing for Transcribe Estoria was easy, just that it was not as complicated as transcribing for the Estoria Digital.

The training for Transcribe Estoria was more passive than for the Estoria Digital, which again, reflected the lower level of difficulty of the task required. This took place as a series of YouTube videos, produced, as the training material for the Estoria Digital was, in both English and Spanish. The training videos move step-by-step from introducing volunteers to manuscripts, assuming no prior knowledge, to quite complex aspects of transcription, such as marking scribal changes, marginalia, and damage. For accessibility, and so that volunteers could refer back as easily as possible, if required, whilst transcribing, we also provided a PDF of each training video. Again, the content was chunked to avoid cognitive overload, and users could move through the training materials at their own pace. The use of videos allowed us to use dual coding by combining audio explanations with images and visual examples illustrating the points we were making, with only necessary animation. Having accessed the video or PDF of all four modules, crowdsourcers were able to practise transcribing. They were also encouraged to ask questions or share comments on Facebook, Twitter, or our blog, and to interact with the team directly but privately using Facebook messenger or email, and many took us up on this to clear up queries. Their queries were as important for the development of the pilot project as the testing-out of the transcription platform was, highlighting omissions on our part, such as missing tags in our WYSIWYG character palette.

The far larger number of individuals transcribing also meant that the one-to-one feedback method we had used in the Estoria Digital was not realistically feasible with Transcribe Estoria, and instead we applied the approach of whole class feedback in schools to our ‘trainee’ transcribers. This whole class feedback took place in emails sent to all transcribers, focussing on general successes and common errors or misconceptions identified when analysing the transcriptions produced within the past fortnight. After thanking volunteers for their hard work, the feedback emails were primarily task-based, as advocated by Dylan Wiliam, Emeritus Professor of Educational Assessment. This diagnostic analysis enabled us to supplement the learning materials we provided to the volunteers, such as a need to explain our approach to usus scribendi, which we were able to see was required by analysing crowdsourcers’ transcription errors and queries, and as such, the whole class feedback was used formatively.

If you are interested in finding out more about the pedagogical considerations behind our training materials, please do get in touch.

You might also like to find out more about our use of crowdsourcing:

Author: Polly Duxfield, 10/07/2020