By Professor Beng Huat See

School of Education, University of Birmingham

Labour’s promise of 6,500 new teachers is unlikely to solve the chronic teacher shortage. The issue extends beyond just a lack of teachers or interested individuals. Despite various financial incentives and the Teacher Recruitment and Retention Strategy—which aims to reduce workload, improve school culture, support early career teachers, and expand flexible working—the problem persists. The question remains: what can the next government do that previous governments could not?

The enduring shortage is not solely about workload and pay, though these are significant factors. The frequent changes in government and educational policies play a crucial role in the fluctuation of teacher numbers. Each new administration and education secretary brings in new policies, which can have an immediate and direct impact on the teaching workforce.

New Labour (1997 to 2010)

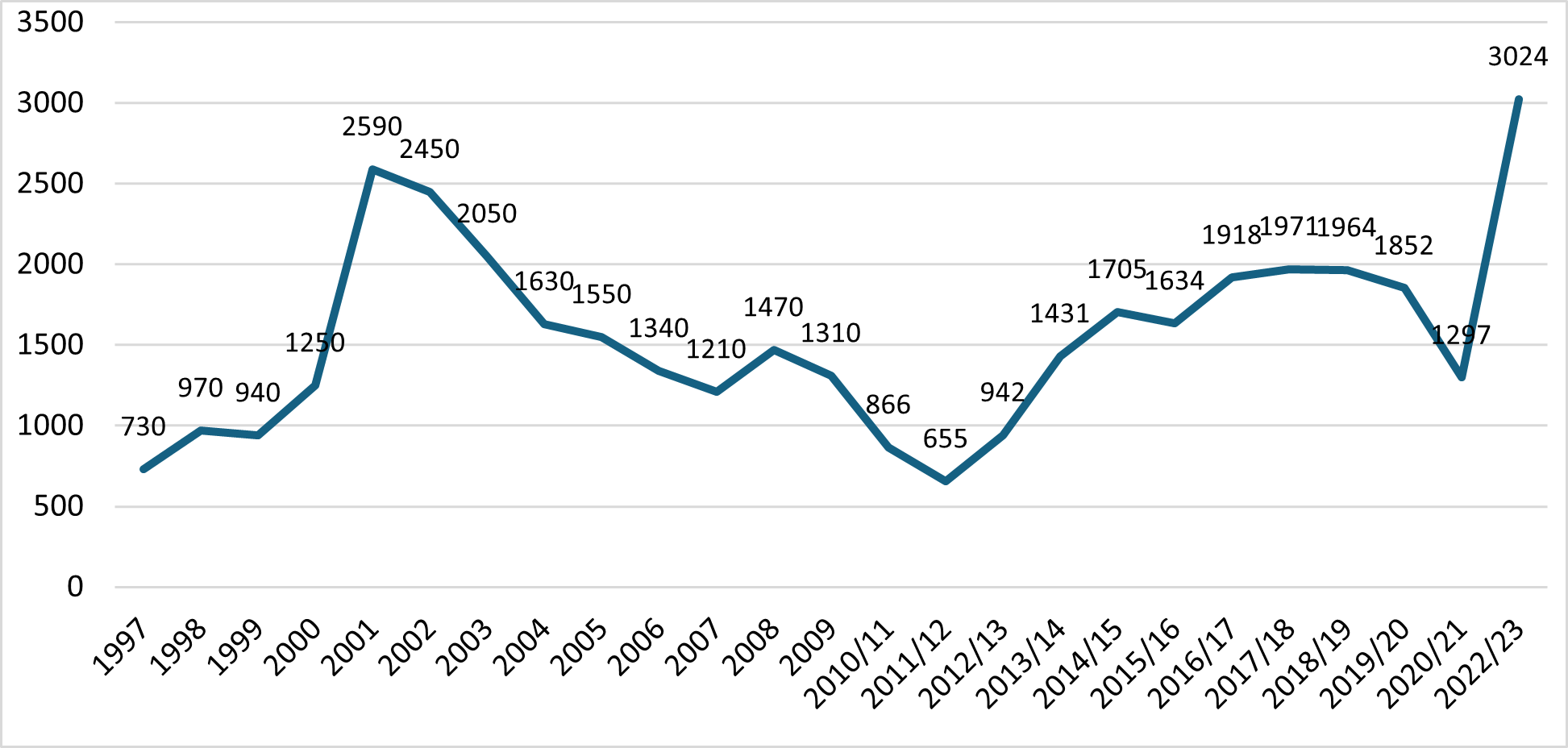

When New Labour took office in 1997, education was a top priority. From 1999, spending per pupil increased significantly, enabling schools to hire more teachers and advertise more jobs. This was reflected in the rise of teacher vacancies, which was often misinterpreted as a shortage.

Starting in 2001, the government began closing small schools, merging some to form larger ones. This consolidation led to a decreased demand for teachers, and subsequently, a drop in the number of vacancies.

Coalition Government (2010 to 2015)

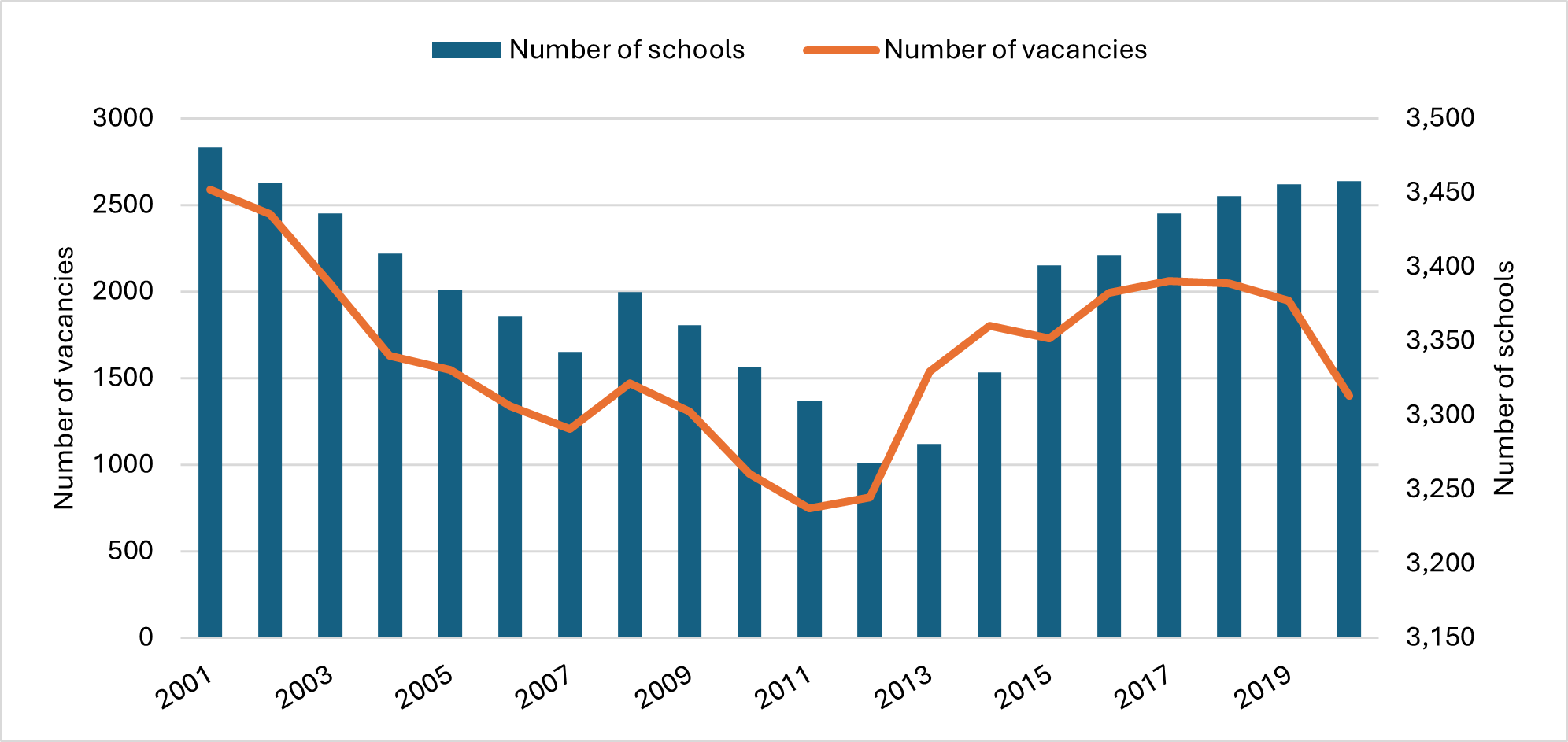

In 2011, the Coalition government introduced various new school types, including Free Schools, Studio Schools, University Technical Colleges, and more academies. The proliferation of small schools, despite their limited numbers, created a high demand for teachers, driving up the number of advertised teaching jobs.

Conservative Government (2015 to Present)

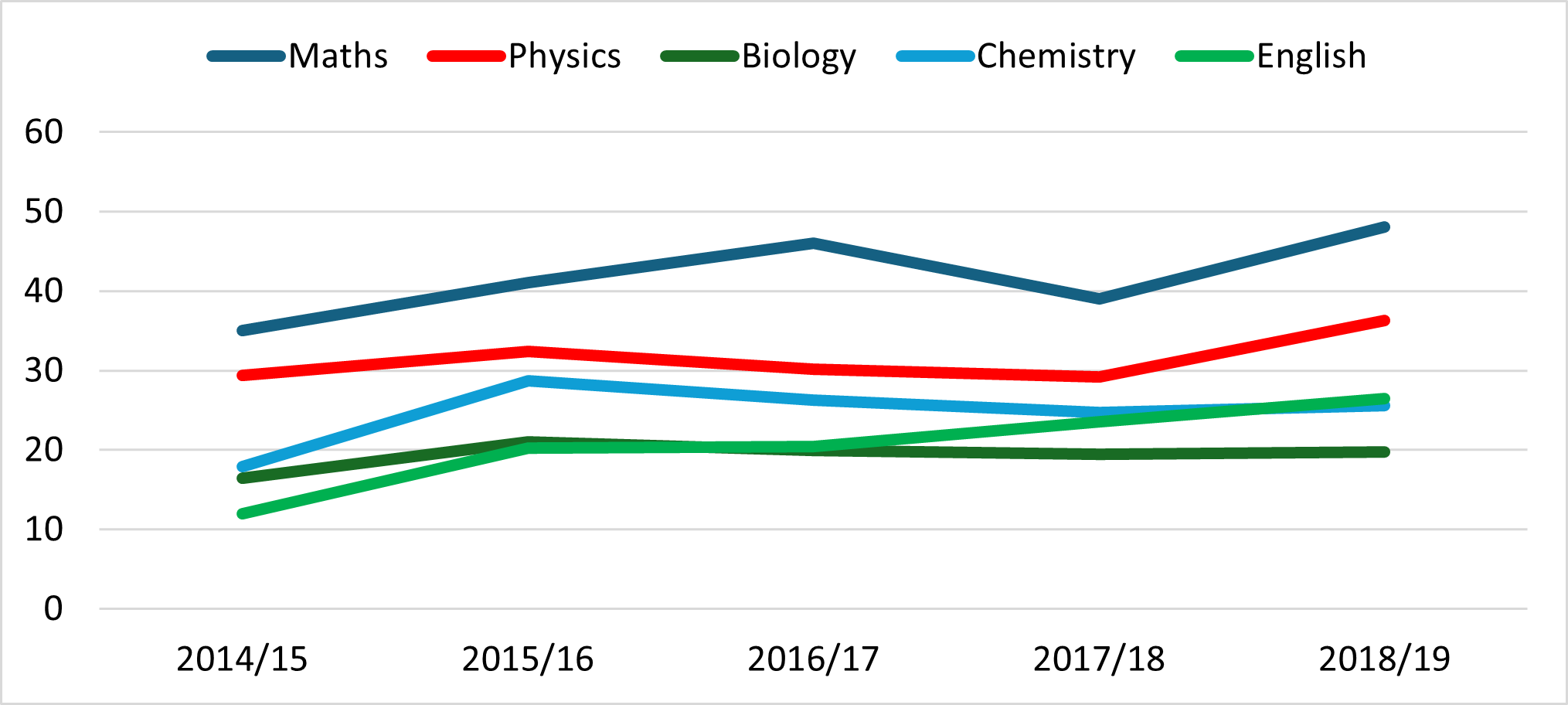

The Conservative government implemented several education reforms, such as extending the education and training age from 16 to 18 and introducing the English Baccalaureate. These changes required more teachers, especially in subjects already facing recruitment challenges, like maths and sciences.

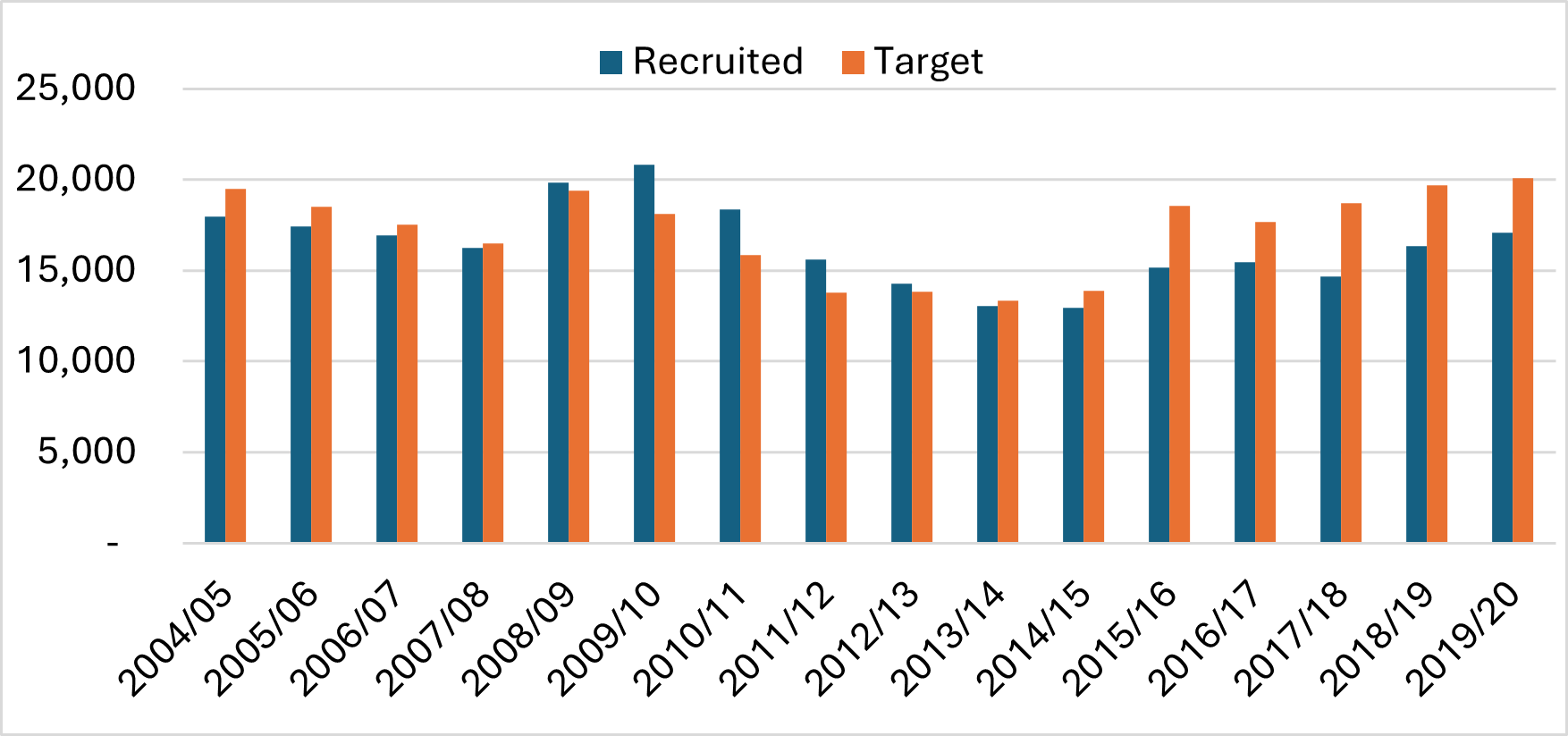

To address this, the Department for Education increased recruitment targets significantly. However, these targets were often unrealistic, such as the 33% increase between 2013/14 and 2015/16. The system struggled to meet these abrupt demands, contributing to the perceived teacher supply crisis.

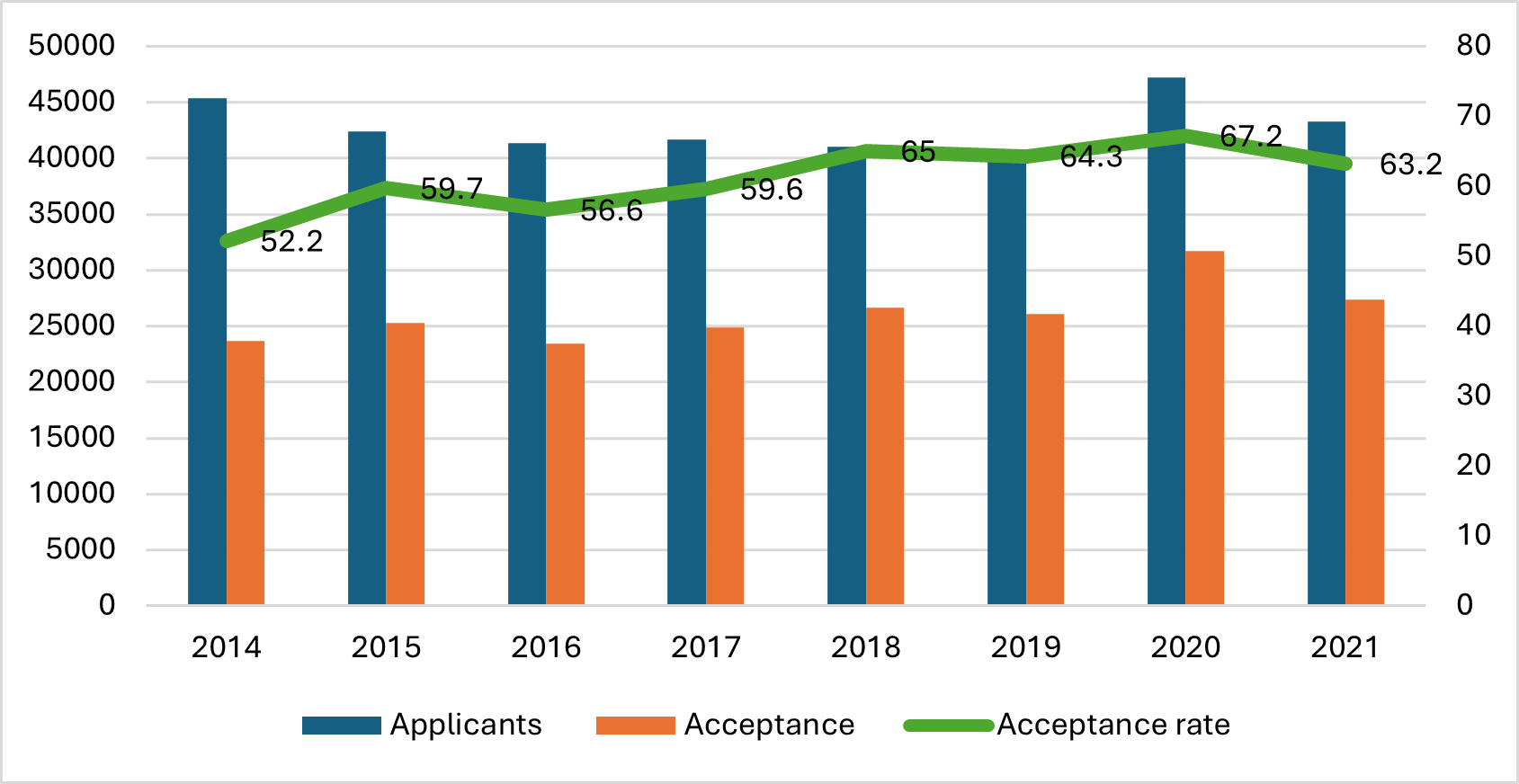

Additionally, while recruitment targets rose, the admission process for initial teacher training became more stringent, reducing the number of training places and, consequently, the number of new teachers. Despite a high number of applicants, acceptance rates remained below 70%, indicating no shortage of interest in the profession.

When considering the number of graduates per year, 50% of maths graduates and 36% of physics graduates would need to be recruited in order to meet the targets set by the government.

Policy Coherence Needed

The ongoing recruitment issues highlight the need for coherent and consistent government policies rather than sporadic attempts to attract more teachers. Labour’s plan for 6,500 extra teachers lacks clarity on how these numbers will be achieved, especially considering the current government’s struggles.

For instance, the government spent nearly £600,000 to attract former teachers back, but only 63 of the 5,729 respondents returned to schools. The National Teaching Scheme aimed to place 1,500 teachers in underperforming schools but was scrapped after recruiting just 24. Similarly, the Troops to Teachers programme offered £40,000 bursaries to ex-service personnel, yet it failed due to low uptake.

A comprehensive approach addressing the underlying policy inconsistencies is essential for a sustainable resolution to the teacher shortage crisis.

Strategies to Boost Teaching Numbers: A Multi-Faceted Approach

Target Potential Teachers While Still in School

To effectively increase the number of teachers, efforts should begin with students still in school. Current policies often rely on monetary incentives aimed at undergraduates, which only attract those already considering teaching careers. Our research shows that most students decide on their career intentions by the time they reach university. Therefore, policies should focus on encouraging students, especially in shortage subjects like maths and science, to think about teaching as a career before they enter university.

Rethink the selection process into teaching

The current selection process for teaching candidates is flawed, with a significant percentage of applicants being rejected. In 2020 alone, 15,080 applicants were turned away, and less than a quarter of maths and physics applicants received placement offers. The stringent demands by the Department for Education (DfE) and Ofsted contribute to these high rejection rates. Furthermore, there is a notable issue with the low acceptance of ethnic minority applicants.

A consistent set of minimum criteria for admissions to initial teacher training should be applied across all providers, ensuring transparency in the selection process. Introducing a central application system, where graduates apply to teach in schools and are allocated centrally, as seen in France and Singapore, could streamline the process.

Remove planning for teacher supply from party politics

The Department for Education in England uses the Teacher Supply Model to estimate the number of teachers needed each year, but this model is limited by unpredictable changes in government policies. Since political agendas and leadership can shift frequently, as evidenced by having five education secretaries in one year in 2022, planning for teacher supply often lacks long-term vision.

To ensure stability and enable long-term planning, teacher supply planning should be removed from party politics and treated as a national decision. This would allow for consistent and strategic planning that aligns with national educational needs rather than shifting political landscapes.

Improve teacher retention

Attracting more individuals to the teaching profession is only part of the solution. Retaining them is equally crucial. Our research shows that while financial incentives can attract candidates, their effects are temporary unless accompanied by improvements in working conditions. People are concerned about money only if they are not paid well. If you ask people what matters to them when choosing their career, money/salary is often top of the list, but if they were asked what they care about and what makes them stay in a job, money becomes less important. Just paying teachers more is not enough. It may be able to attract people into teaching, but what will make them stay is enhancing job satisfaction through better working conditions.

In conclusion, a comprehensive approach that includes early targeting of potential teachers, revamping the selection process, depoliticizing teacher supply planning, and improving working conditions is necessary to address the current teacher shortage effectively.

- Find out more about Professor Beng Huat See

- Back to Social Sciences Birmingham

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.