In the first fragment of the Estoria de España which we are transcribing, on the founding of the city of Seville, it is possible to see a range of interesting phenomena related to the act of copying and to linguistic change and its written manifestation. In truth, when we read and transcribe any premodern text, even the most regular or anodyne (not, of course the case of Transcribe Estoria :-), it is almost impossible not to trip over some feature or other that reminds us of the unpredictable, marvellous act of writing, or of the evolution of language, or of the meeting of art and culture or of the infinite forms of human thought. For there is a treasure hidden in every line of a manuscript, a far-off aleph of parchment and ink in which we can recreate ourselves over and again.

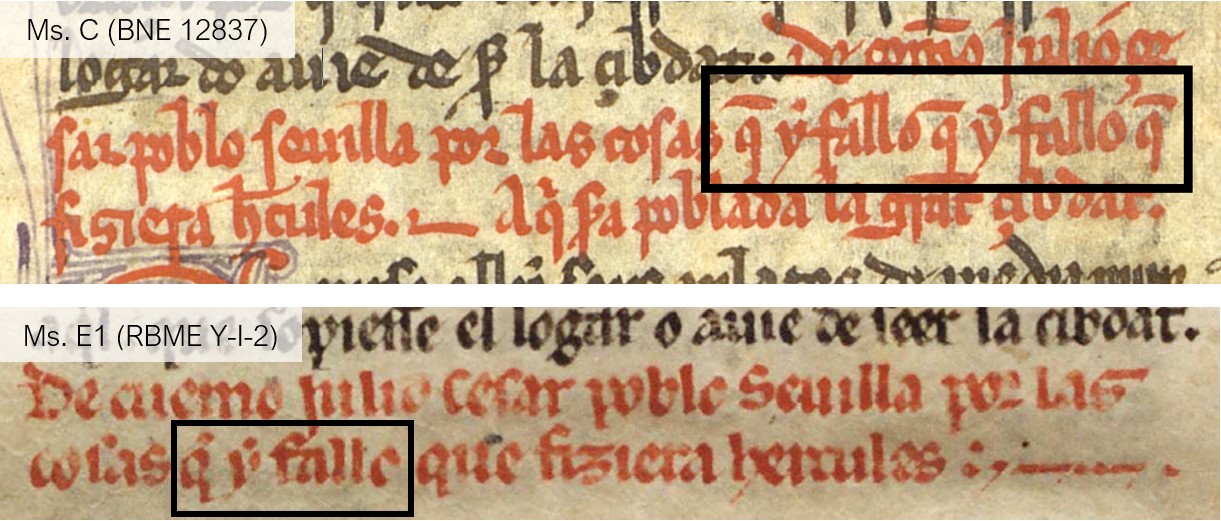

Let’s take a look, in the first instance, at just how the scribe of our manuscript unwittingly commits copying errors, but also how, at different moments, he provides us with interesting textual variants. We can see this straight away by comparing the image of the manuscript with the base text; remember that this base text is a transcription of the royal manuscript E1, and is therefore a product of the Alfonsine scriptorium. If we look at the rubric, or chapter heading, in red we can see a sequence that is duplicated (“que y fallo”). It is highly likely that this was due to the presence of the relative pronoun “que” – notice that, at the end of the same line, after the duplication the following phrase also begins with “que”. The scribe’s eye probably skipped back when he looked up to see what he had to copy, and on seeing the second “que” (“que fiziera Hercules”) he repeated the previously copied sequence in error (“que y fallo”). He clearly did not realise his error (known as “dittography”), because there is no correcting mark – the text is not struck through, scraped or underdotted. But then, how often has this happened to us? Imagine the typical report or document written at high speed without correction – especially when written on a computer. “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone…” J And while we are commenting on the rubric, you will have noticed also that the rubric in C is more lengthy that that of E1. Perhaps it was more difficult for you to decipher what follows “hercules”, since there is no base text with which to compare it: after the point and the small decorative line, the rubric in C continues “Aqui sera poblada la grant çibdat” (don’t forget to include the correct abbreviations!).

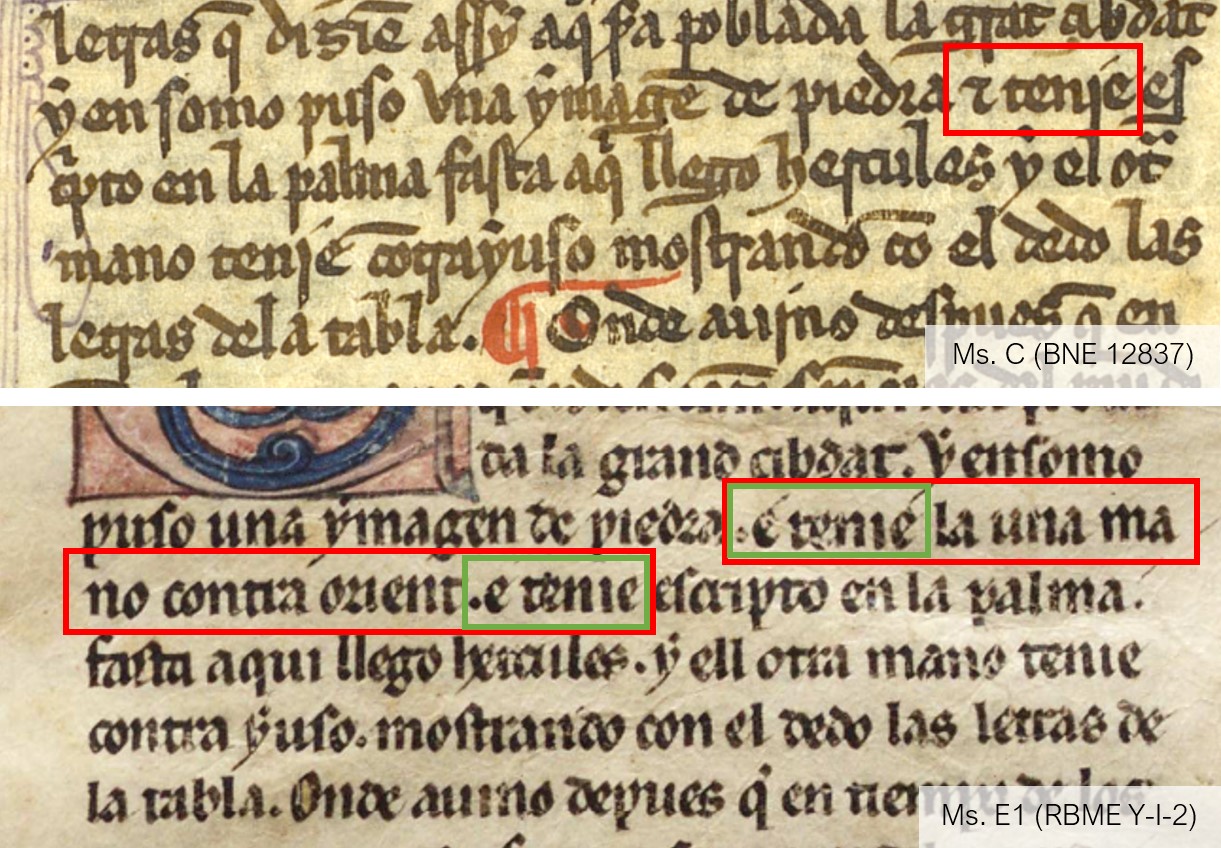

The same type of confusion, caused by reading the same word twice, has different consequences a little further on. Instead of repeating a part of the text, the scribe skips over a sequence which ends with the same word (or a very similar one) as that which finishes the previous sequence, thereby omitting to copy a phrase. We can see an example of this a few lines into the chapter (lines 5-6) when we read that Hercules places an “imagen de piedra” on the monument made of seven pillars and the “table de marmol” which he erects where Seville will subsequently be founded. On this “imagen” it is said that one of the hands -open towards the east- had written on the palm the words “fasta aqui llego Hercules”, and the other hand pointed downwards towards the letters of the inscription on the marble slab. If you look carefully at the text of C, comparing it with the base text, you will notice that in C, the words “mano contra orient” are missing. Where is the error then? In the word “tenie” (or more accurately, in the sequence “e tenie” preceded by a full stop) which we have highlighted in the next image. E1 has the text “Y ensomo puso una imagen de piedra, e tenie la una mano contra orient e tenie escrito en la palma…”. The copyist, in error, skipped from the first “tenie” to the second one, thereby omitting the sequence in between (“la una mano contra orient”). Of course, when transcribing this passage, we are asking you to copy faithfully the text as it appears in C, that is, to delete all of the sequence skipped over by the scribe of C. In a subsequent phase of our research, we will note these and similar errors and this will allow us to rate the textual accuracy of the different copies.

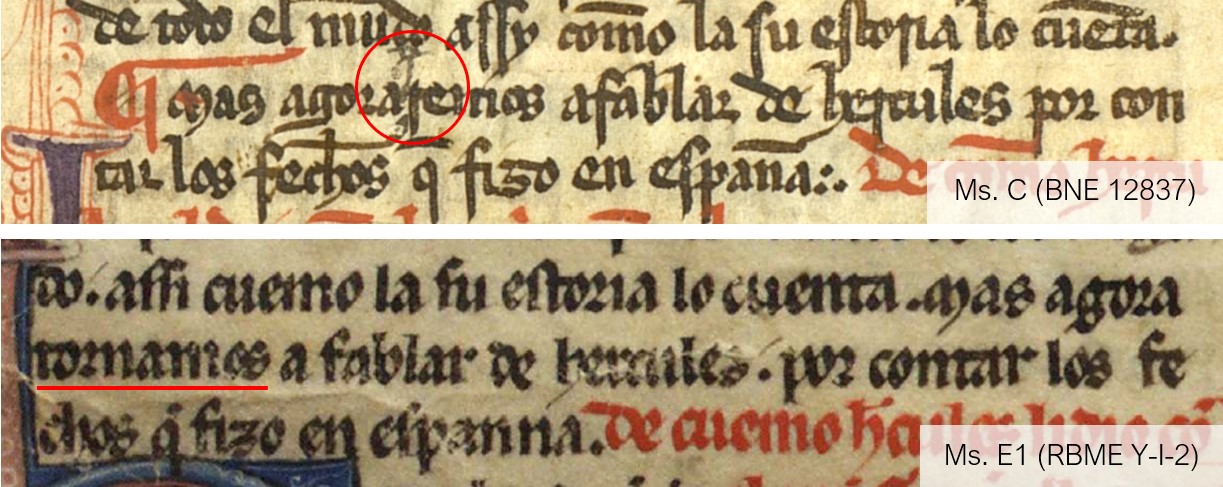

Let’s have a look at another copying error, this one is mentioned in our training materials. In the last line of the chapter, just after the pilcrow (¶), the text states: “Mas agoraremos a fablar de hercules por contar los fechos que fizo en espanna”. There is a clear error in this form “agoraremos”, the text should read “agora (que)remos”. The scribe seems to have become confused while copying the E1 text (in which the verb form is “tornamos”) and subsequently he, or some other corrector, added the syllable “que” in the upper interlineal space.

But beyond the textual differences (whether errors or innovations), when you compare the two texts and correct the base text, it is extraordinarily satisfying to identify the graphic and/or linguistic differences that are there to be seen. It is akin to being present for the slow and vacillating evolution of language and writing. If you have transcribed slowly, you will have noticed that the two manuscripts employ, either in general or exclusively, one of two variants of the same word, and generally you find the older one in E1. Thus, for example, we see the diphthongized form “cuemo” in E1, but “como” in C; the forms ending in <-d> ‘grand’ and ‘segund’ (E1) but ‘grant’ and ‘segunt’ (C) con <-t>; the presence of the doublé intervocalc <s> (to represent voiceless /s/) in the verbal forms ‘fuessen’ or ‘fiziesse’ (E1), but ‘fuesen’ or ‘fiziese’ (C) with a single <s> – the sign of the absence of a voiced /unvoiced distinction here; the use of <c> before <e,i> in such cases as ‘cibdat’, ‘obedecie’ or ‘desabenencia’ (E1), but the uwse of <ç> cedilla: ‘çibdat’, ‘obedeçie’, ‘desabenençia’ (C); apocopated (that is, forms with a loss of final vowel) forms ‘orient’, ‘cinc’, ‘tod’, ‘nol’ or ‘ques’ (E1), but‘oriente’, ‘çinco’, ‘todo’, ‘no le’ or ‘que se’ (C); the forms ‘depues’ and ‘estonce’ (E1) but ‘despues’ and ‘entonçe’ (C); the adverbial ending ‘-mientre’ (‘primeramientre’, E1) but ‘-mente’ (‘primeramente’, C); the possessive ‘so’ (E1) but ‘su’ (C); the adverb ‘o’ (‘donde’, E1) and ‘do’ in C; la preposition ‘pora’ (E1) rather than ‘para’ (C); the form of the toponym ‘catalonna’ (E1) and not ‘cataluenna’ (C), etc.

Of course, these are not always systematic differences (as you will see as we work our way through subsequent texts), but they are indications of tendencies of progressive linguistic change reflected in writing which tells us something about the context in which they occurred. Remember, though, that the chronological difference between E1 and C is not so great (about fifty years, give or take, between the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th), but it is still sufficient to observe these changes. Bear in mind also that medieval writing is not confined by strict orthographic guidelines, as is the case now, for in the same text (even in the same page, column or line) you can see multiples ways of writing the same word. Don’t pass over these, apparently insignificant, details, because they are the traces of our linguistic and cultural past – waiting here for us to find them and give us the satisfaction of someone who has found a nugget of treasure in the dark night of the past.

Ricardo Pichel

1 thought on “On the linguistic value of the manuscript and the innovations and mistakes of the scribe”

Comments are closed.