Andrew Nickson has extensive worldwide experience of teaching, research and consultancy on public administration reform, decentralisation, and the reform of basic service delivery and regulation of privatised public utilities. He has been advisor to DFID, OECD, British Council, UN agencies, Inter-American Development Bank, World Bank, and the European Union on numerous consultancies. This post is based on the introduction to The Paraguay Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke University Press, 2012), edited with Peter Lambert.

Paraguay has long been seen as one of the forgotten corners of the globe, a place that slips beneath the radar of most diplomats, academics, journalists, and tourists in Latin America. Paraguay is a country defined not so much by association as by isolation. The renowned Paraguayan writer Augusto Roa Bastos famously remarked that Paraguay’s landlocked isolation made it like an island surrounded by land.

Yet Paraguay is developing and globalizing fast. It is a major exporter of electricity, soy, and beef; its economy grew by 14 percent in 2010, the second fastest in the world; and it has one of the world’s largest deposits of titanium. Asunción is waking up from its long siesta to the pressures of a rapidly growing population, the choking smell of fumes from seemingly unending traffic jams, and the fear of crime around every corner. The deafening whine of locally produced Chinese mopeds has replaced the sound of crickets in most town squares.

However, this long, historical isolation has meant that Paraguay has been largely neglected by historians, journalists, and travel writers. Ignorance has allowed Paraguay to become a perfect blank space for others’ writing and imaginings. Viewing Paraguay with a mix of suspicion, humor, fondness, and disdain, they have too often glided over complex issues of culture and politics, replacing them with tired references to either crazy wars, endemic corruption, Nazi war criminals and savage natives, or tin-pot dictators and brutal tyrants.

However, this long, historical isolation has meant that Paraguay has been largely neglected by historians, journalists, and travel writers. Ignorance has allowed Paraguay to become a perfect blank space for others’ writing and imaginings. Viewing Paraguay with a mix of suspicion, humor, fondness, and disdain, they have too often glided over complex issues of culture and politics, replacing them with tired references to either crazy wars, endemic corruption, Nazi war criminals and savage natives, or tin-pot dictators and brutal tyrants.

Repeatedly presented as an isolated and underdeveloped cultural backwater, a dangerous but attractive land where magical realism and reality seem to collide, Paraguay is often portrayed as the epitome of exoticism, peculiarity, and exceptionalism. Such an image is insidious because it conveniently overlooks and ignores the less sensationalist reality of a country struggling against underdevelopment, foreign intervention, poverty, inequality, and authoritarianism, and of individual and collective struggles for social justice against enormous odds.

But the lure of Paraguay has remained constant. For centuries foreigners have viewed the country through their own ideological and religious gaze, often seeking to create their own utopias over existing realities. Paraguay has been a melting pot of immigrants; Spanish, Italian, German, Balkan, middle eastern, black African, Russian, Japanese, Korean, South African, Latin American have all mixed in Paraguay.

For the Spanish, Paraguay offered a relatively safe and comfortable location for settlement. The Jesuits organized Guaraníes into productive communities, indoctrinated them into Catholicism, but protected them from marauding Brazilian slave traders. When independence came in 1811, Dr. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia sought to avoid the anarchy and chaos of other newly independent Latin American states by establishing a dictatorship that destroyed the power of the Spanish elites, the church, and the landowning class. His successor Carlos Antonio López (1840–62) oversaw Paraguay’s emergence as an important regional power, complete with railway, telegraph lines, a shipyard, and an iron foundry.

Then Francisco Solano López, the son of Carlos, led Paraguay into the catastrophe of the Triple Alliance War (1864–70) against Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, which brought a dramatic end to Paraguay’s state-led development. In a war against Bolivia (1932–35), Paraguay gained in terms of territory but lost some thirty to forty thousand lives in the process, many of them from thirst. Scarcely recovered, the country fell into a brutal civil war (1947) and then, seven years later, into the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner (1954-89).

Stroessner’s former military strongman, General Andrés Rodríguez, introduced a new constitution, free elections, and civil liberties, but the Colorado Party, the mainstay of the Stroessner dictatorship, continued to win elections throughout the next two decades. Only in 2008 did the opposition candidate, the former bishop Fernando Lugo, manage to end over sixty years of Colorado rule and usher in his aptly titled ‘New Dawn’ for Paraguay.

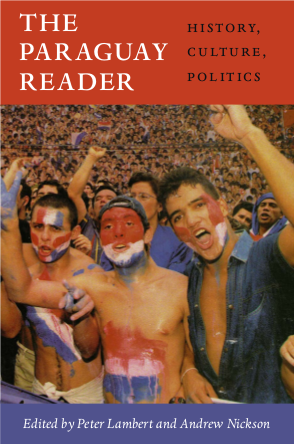

Our aim in writing The Paraguay Reader has been to produce an enjoyable, informative, and well-structured anthology of writings on the politics, society, and culture of the country. Six of the Reader’s seven sections are chronological, from the first, ‘The Birth of Paraguay’, to the sixth, ‘A Transition in Search of Democracy’. The final section, ‘What Does it Mean to be Paraguayan?’ examines key issues surrounding national identity, cultural characteristics, ethnicity, language, and gender. Throughout we have contextualized the extracts, many of which are abridged, by using explanatory introductions.

Wherever possible we have tried to include ‘voices from below’ or at least contemporary accounts by Paraguayans. There is a lack of written historical testimonies and memoirs by Paraguayans, however, and so we have included a number of pieces written by foreigners. Wherever possible we have also tried to use voices from the period under consideration. Again, suitable extracts have often been difficult to find, and thus in some cases we have opted for more recent analyses by outstanding historians, including Branislava Susnik, R B. Cunninghame Graham, Harris Gaylord Warren, Ignacio Telesca, and Thomas Whigham.

Most of the texts that we selected are being published in English for the first time, and some have not previously been published in any language. ‘Lincolnshire Farmers’, ‘How Beautiful is Your Voice’, and ‘The Psychology of López’ are all published here for the first time, while ‘The Sufferings of a French Lady’ was published just once in Buenos Aires in 1870 and is hardly known. We believe the translations are of a very high quality, not only in terms of grammatical and linguistic accuracy, but also in terms of style, fluency, and ‘voice’.

We have tried to be as eclectic as possible in terms of the tone, style, and nature of the extracts we have chosen. hence we have included examples of testimonies, light-hearted journalistic pieces, academic analyses, political tracts, poetry and song, literature, and even a recipe. At the same time we have also tried to cover all major historical events, sectors, and issues. We hope that, in so doing, it will help dispel the many myths about the country, and that it will strike a small blow for people’s history over fantasy, cliché, and stereotype.

Photo courtesy of Natalia Daporta via Flickr.com, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.