Andrew Coulson is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow in the International Development Department at the University of Birmingham and author of Tanzania: A Political Economy (1982, new edition 2013). He was an ODI Fellow in the Ministry of Agriculture in Tanzania in the 1960s, and lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam in the 1970s, where he taught many of the country’s future leaders, including President Kikwete. Between 2016 and 2018 he was Chair of the Britain Tanzania Society.

Antony Ellman is an agronomist and socio-economist who first went to Tanzania in 1962 to work on the Government’s settlement schemes. He became the manager of Upper Kitete which was one of the models used by President Julius Nyerere in his concept of ujamaa villages. In more recent years he has worked in the country as a consultant on conservation agriculture, fair trade and linking farmers to markets. He plays an active role in the Tropical Agriculture Association.

Emmanuel Mbiha has recently retired from the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness at Sokoine University of Agriculture in Morogoro, Tanzania. His PhD is from Wye College, University of London. He specialises in agricultural marketing and price and policy analysis.

Many important discoveries about agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa are in danger of dropping out of syllabuses and teaching. Courses are increasingly based on books prepared for students in the US or Europe, where agriculture can be reduced to a set of activities or “enterprises” which are evaluated separately. That may be useful for a large farm growing just one or a relatively small number of crops, with owners who can hire extra labour or machinery if they need it. It is not appropriate for a farmer with a small amount of land and a limited amount of labour who above all needs to minimise the risks that may arise if there are crop or market failures. That will only be achieved by planting many crops, at different times, with different varieties of seeds with different resistances to drought. This was well understood in the 1970s – it is in danger of being forgotten today.

Little use is being made of local case studies – another big loss since the 1970s. There is a reversion to approaches based on a single discipline – economics, anthropology, science or engineering – when a multi-disciplinary approach gives a much better understanding of what is needed to increase agricultural productivity.

A new textbook

To remedy this three of us have written a textbook*. We come from  different backgrounds but have spent much of our lives studying agriculture in Tanzania. Our book provides a unique aid for teachers and students. It will also help policy-makers who need to understand the possibilities, and the limitations, of the technologies on offer anywhere where soils are fragile and the climate unpredictable.

different backgrounds but have spent much of our lives studying agriculture in Tanzania. Our book provides a unique aid for teachers and students. It will also help policy-makers who need to understand the possibilities, and the limitations, of the technologies on offer anywhere where soils are fragile and the climate unpredictable.

Each chapter starts from first principles but ends with discussion of complex concepts such as climate change or genetic modification. When it uses technical terms, it defines them in simple language. Each chapter ends with one or more case studies of local projects or situations. There are exams or essay questions, and bibliographies of materials that can be freely downloaded from the net. It is interdisciplinary, drawing on science and on the social sciences.

Farm Systems Studies

Some principles appear repeatedly. One has already been alluded to. In the 1960s and 1970s, agricultural economists developed the principles of what was then called Farm Management Studies, today more often Farming Systems Studies. This involves collecting information about the requirements of labour at each point in the growing period to grow an acre of a crop – and also an estimate of the likely yield if it is planted at different times. With this information for a range of possible crops, it is easy to create linear programming models which will help farmers to maximise the income from a limited amount of land and labour.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the recommendations that result are often close to what farmers are doing anyway. It is unusual for the optimum to come from planting just one crop. Once a basic model has been created, it can be reworked to show the influence of inputs, such as inorganic fertilizers, or changes in prices achieved when crops are sold, or the consequences of a failure in the rains.

The researchers of the 1970s, such as Michael Collinson and Frank Ellis, discovered that this kind of information was relatively easy to collect, because farmers had good understandings of the sizes of their plots and how much labour would be needed for each agricultural task – preparing the land, planting, weeding, harvesting, etc. They also remembered how much they had harvested. The research showed that there was usually an economic logic to what the farmers were doing – planting more than one crop, at different times, mixing crops together in the same field (intercropping), being careful about how much they spent on inputs, keeping animals as well as crops.

Conservation agriculture

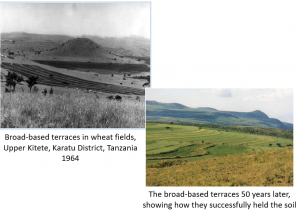

Another principle is that of conservation agriculture, made even more urgent by climate changes. Many of the soils in Africa are fragile and at risk of erosion from wind or water. Population increases have meant that systems of permanent cropping have replaced shifting cultivation, which had its problems but at least allowed soils to recover. Where the same soils are used year after year, especially for the same crop, they risk running out of essential minerals.

Conservation agriculture can minimise the risks of erosion and keep as much of the humus (organic content) of the soil as possible. This will enable it to hold water and provide a good environment for crops to grow. There may be times when inorganic fertilizers are necessary, but if the humus content is low they risk being washed away by heavy rain.

Commentaries on other policies

The structure of our book, each chapter starting with basic information but ending with commentaries on policies, allows important points to be raised. For example:

- Many large irrigation projects have failed because means of paying for maintenance or ensuring that the water is distributed fairly were not built in from the start.

- Agricultural research has huge potential, but only if the researchers maintain close links with farmers and understand their problems.

- Much agricultural extension is ineffective because the extension workers are not up to date in their knowledge, and awareness of new opportunities, or because they do not understand much of the relevant knowledge the farmers already have.

- The use of inorganic chemicals has polluted watercourses and lakes, and put at risk those who spread insecticides or who live nearby – and there are longer-term risks from over-dependence on a few crop varieties.

There are many myths or half-truths about agriculture, and the book does its best to debunk them. It shows that there are opportunities to increase production from farms of all sizes. Small farms have to be sufficiently profitable to keep very large numbers of people in employment, because, in most African countries for at least a generation to come, there is no other realistic way in which they can find employment. Agrochemicals and genetic modification may assist crop and livestock production, but organic farming can often also be viable. The final chapters are about women’s contributions to agriculture, the possibilities of a new “Green Revolution” in Africa, and a set of broad principles to guide agricultural production. The book ends with a quiz about attitudes to small farmers.

So if you are involved in any way with agriculture in Africa, or teach courses on rural development, you need this book.

* Andrew Coulson, Antony Ellman and Emmanuel Mbiho Increasing Production from the Land: A Sourcebook on Agriculture for Teachers and Students in East Africa, published by Mkuki na Nyota in Dar es Salaam in 2018, and available from the African Book Collective or the authors in the UK.