By David Hudson, Professorial Research Fellow in Politics and Development

International Development Department, University of Birmingham

Who are these people who give their time, and work with and for international development organisations?

People become engaged with international development in lots of different ways and for many different reasons. Some people donate to a charity because a friend is running a marathon, some write to their MP, newspaper or tweet. Others choose to buy Fairtrade products and boycott others. These actions don’t, for the most part, take much time or effort. Volunteering – when people freely give away their time and skills to help others, whether in the UK or overseas – is an altogether costlier proposition. And in the case of international development, what is more the efforts are towards distant strangers.

What types of people volunteer?

Who are these people who give their time, and work with and for international development organisations? With colleagues at the University of Birmingham (Danielle Beswick and Mattias Hjort) and UCL (Jennifer vanHeerde-Hudson and Paolo Morini), I’m analysing data from the Aid Attitudes Tracker to understand why individuals in the UK volunteer at home or abroad on international development issues. The insights are based on a survey that went out to 8,115 adult respondents during the period October-November 2016 (fieldwork conducted by YouGov). Here’s what we know.

Our nationally representative sample suggests that 10% of the UK adult population have volunteered for a development organisation in the UK and 5% have volunteered abroad. There is, of course, some overlap – with a quarter of the 10% having volunteered overseas and in the UK. Which means 12% of the UK population overall has volunteered for an international development organisation at some point in their life.

Women are slightly more likely to volunteer in the UK than men, and men are slightly more likely to volunteer overseas than women. Volunteers tend be younger. The average age of UK volunteers is 43 years old and overseas volunteers is 39 years old, compared with 48 for non-volunteers.

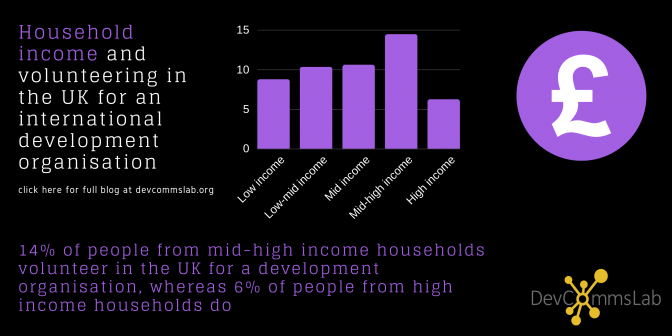

Individuals from high income households (£150k+) are the least likely to volunteer, whereas individuals from mid-high income households (£70-£149k) are the most likely. Education levels are positively correlated with likelihood of volunteering, peaking at undergraduate degree level.

Muslims are most likely to volunteer in the UK (24%) and Hindus overseas (23%). Black, Asian, and minority ethnic respondents are more than twice as likely to volunteer than White respondents – however, the vast proportion of UK volunteers are white, accounting for 86% of all international development volunteers at home and 79% of those volunteering overseas.

Supporters of Plaid Cymru, SNP, the Green Party and the Lib Dems are the most likely to volunteer. Labour supporters (13%) are twice as likely to volunteer in the UK than Conservative supporters are (6%) but, interestingly, when it comes to volunteering overseas there is very little difference between the propensity of Conservative (4%) and Labour (5%) supporters to volunteer for international development organisations.

Why do people volunteer?

So, if this is what volunteers ‘look’ like, why do such individuals willingly give their time to help distant strangers? Many people, naturally, assume that volunteering is driven by prosocial values such as altruism. But there are alternative more egotistic theories, such as potential financial benefits, social recognition or positive feelings about oneself. Self-interest makes sense for domestic volunteering – especially for the PTA of your child’s school, for example – but what about distant strangers?

We ran two regression models to simultaneously test the impact of multiple factors on the likelihood of volunteering in the UK and volunteering overseas. Notably we did not find that the benefits of development efforts or the perceived morality of assistance were significant. Instead, we found that the following did:

- If respondents felt like they could make a difference – either to poverty or more generally to public affairs – they were more likely to volunteer.

- Positive social norms, i.e. when individuals feel surrounded by others with prosocial values, also increased people’s propensity to volunteer in the UK, but not overseas.

Why does this matter?

There are some important insights here for international development organisations, NGOs, and charities working with volunteers.

- ‘Feeling you can make a difference’. Creating, and reinforcing, a sense of personal efficacy is vital in persuading people to give their time and skills.

- One in eight. 12% of people have volunteered for an international development organisation at some point in the past. This is a significant proportion of the population.

- Look beyond the usual suspects. While being a Conservative supporter and being influenced by social norms are negatively correlated with volunteering in the UK, they do not matter for overseas volunteering. This means that the profile of potential overseas volunteers is a little bit wider than many might assume. The decision to volunteer is more down to the individual and not dictated by their social milieu.

P.S. did you know that volunteers provide make especially good messengers: using volunteers in charitable appeals is extremely effective at getting other people to donate or sign a petition; much better than celebrities or politicians.

- More about Professor David Hudson at the University of Birmingham

- This post was originally published on DevCommsLab

- Back to Social Sciences Birmingham