By Professor Joanne Murphy

Department of Management

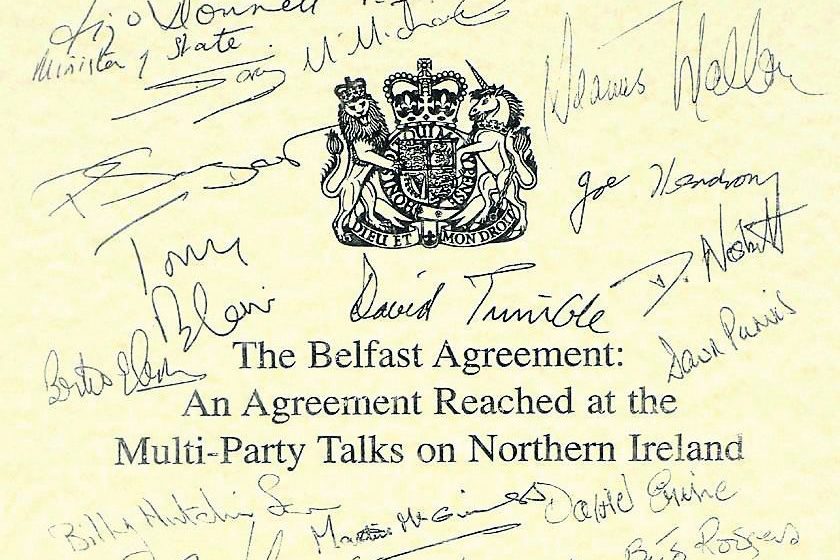

The Good Friday or Belfast Agreement of April 10th 1998, is an international Treaty signed by the British and Irish Governments and is generally regarded to have brought about an end to the long-running conflict in Northern Ireland known as ‘the Troubles’.

The Agreement was the culmination of three decades of work to build peace and follows on from previous accords such as the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, and the more recent Joint or ‘Downing Street” Declaration of 1993 which brought about the IRA ceasefire. The Good Friday settlement clarified important issues such as the constitutional position of Northern Ireland now and in the future, the governance of Northern Ireland regionally, issues of paramilitarism and the release of paramilitary prisoners, provisions for the reform of policing and justice, and cultural parity of esteem between Northern Ireland’s two communities.

The Structure of the Deal

The Agreement itself is made up of two parts: a Multi-Party Deal between most of Northern Ireland’s political parties, and an international treaty between Britain and Ireland. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) were the only major political party in NI to oppose the Agreement. The Agreement has a three-strand framework. These strands represent an attempt at a resolution of the historic set of disputes within Northern Ireland itself, between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and between the states of Britain and Ireland.

As such, Strand One deals with the status and system of government in Northern Ireland, including the Northern Ireland Executive and the devolved Assembly. Strand Two focuses on the relationship between Northern and Southern Ireland and makes provision for a North/South Ministerial Council, a North/South Interparliamentary Association, and a North/South Consultative Forum. Strand Three deals with East-West issues and contains provision for a British- Irish Intergovernmental Conference, a British-Irish council and an expanded British-Irish Interparliamentary body. The three strands are designed to be both interlocking and interdependent.

Principle of Consent

In addition to the provisions above, the Agreement recognised that the majority of people in Northern Ireland wished to remain part of the United Kingdom and that a substantial section of the people of Northern Ireland and a majority of those in the Republic of Ireland wished to bring about a United Ireland. Both aspirations were acknowledged as legitimate. This acknowledgment meant that for the first time the Republic of Ireland accepted that NI was part of the UK. The Irish constitution’s articles 2&3 were amended to recognise this, conditional upon the consent for a United Ireland from majorities of people in both jurisdictions on the island. In addition, the British parliament repealed the Government of Ireland Act 1920 which had established Northern Ireland through partition and asserted a territorial claim over the whole of Ireland. These processes enshrined the centrality of what is known as the ‘principle of consent’ and means that the future of Northern Ireland rests in the hands of the people of Northern Ireland.

Identity and Impartiality

Irrespective of constitutional status, the Agreement also gave rights to the people of Northern Ireland to identify as British, Irish or both (in terms of citizenship). Importantly, it was also agreed that irrespective of the constitutional position of Northern Ireland, the sovereign government with jurisdiction over Northern Ireland would exercise its power with ‘rigorous impartiality on behalf of all the people in the diversity of their identities and traditions and shall be founded on the principles of full respect for, and equality of, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, of freedom from discrimination for all citizens, and of parity of esteem and of just and equal treatment for the identity, ethos and aspirations of both communities’.

Approval

The Agreement was approved in referenda across the island of Ireland on the 22nd May 1998. The referendum in Northern Ireland asked for support for the multi-party agreement. The referendum in the Republic of Ireland asked for support for the Agreement and the significant constitutional changes it would require. In Northern Ireland 71.1% voted Yes to the Agreement. In the Republic of Ireland, the Yes vote was 94.39%.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.