In all our haste to look forward with The Routledge Companion to World Cinema we sometimes forgot to look back too. Obviously new cinema movements don’t spring forth from nothing but exhibit, if only after careful dissection, the influences, legacies and reactions against other movements and examples of World cinemas. It’s no use looking at the independent American cinema of the 1990s without looking first at the French New Wave. It’s no good looking at film noir without watching German expressionism. It will be pointless watching Fast 8 (2017) without watching Furious 7 (2015) first.

Nowhere is this more true than in the study of emerging cinemas, which need to be contextualised in a cinema history and a history of cinemas. Understanding where they’re coming from indicates where they’re going. Traces of Third cinema, for example, or remnants of neorealism point to a political purpose, while references to Un chien andalou or The Searchers signal other ambitions.

When can emerging cinemas be labelled a ‘movement’ or a ‘wave’? Is a Grand Jury prize at Cannes too soon? Is a DVD box-set too late? The tricky task was recognised by the contributor of our next chapter, Jonathan Driskill, who took on the job of organising a coherent approach t the understanding of Southeast Asian independent cinema. Jonathan is Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at Monash University, Malaysia and is the author of Marcel Carné (2012) and The French Screen Goddess: Film Stardom and the Modern Woman in 1930s France (2014). This was his abstract.

Southeast Asian Independent Cinema: A World Cinema Movement?

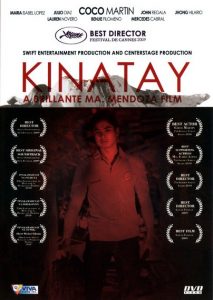

This chapter starts with an overview of film in Southeast Asia, covering popular and auteur cinema (such as the work of celebrated Philippine directors Lino Brocka, Mike de Leon and Ishmael Bernal), before focusing on the recent boom in digital independent filmmaking, which has been growing since the early 2000s. This has seen a number of Southeast Asian filmmakers achieve significant international success, such as Brillante Mendoza (Philippines), who won the Best Director award at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival for Kinatay (2009), and Amir Muhammad (Malaysia), whose political documentary (2003) performed well at a number of international film festivals (including Sundance). The chapter examines the main aesthetic and political features of these films and questions whether they constitute a coherent film movement in the manner of earlier classic World Cinema movements, such as Italian Neorealism, the French New Wave and Cinema Novo.