In this case study we hear from Zhuangchen Wu, a PhD student in Economics, who has been making use of BlueBEAR to enable his research into understanding price-setting behaviour.

My research focuses on understanding price-setting behaviour using data from online sellers. Properties of price-setting have important implications for macroeconomic modelling, especially for monetary policy design. Unlike official inflation statistics that are reported monthly/quarterly, I collect and analyse daily price listings to reveal various patterns of pricing moments. Given the large scope of data, BlueBEAR’s High-Performance Computing (HPC) service is essential for my research.

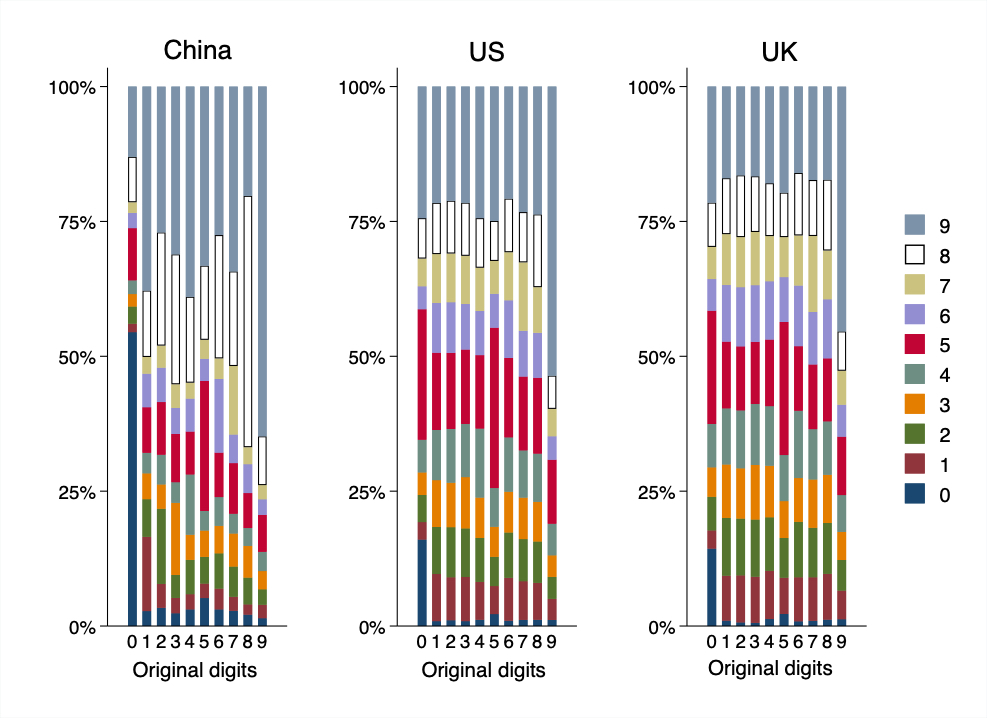

One of my research projects focuses on digits in prices. In supermarkets and online shopping platforms, we can always observe prices ending with “99” or “9”. We believe these prices are “cheaper” and the retailers prefer to set prices ending with price points to boost consumption. These prices tend to be maintained for a long time, which leads to above-average price rigidity. However, other digits matter in some countries. For example, figure “4” (“8”) is considered unlucky (lucky) in China, but neutral in the US and the UK. Hence, I explore whether there is an underrepresentation of “4” and a prevalence of “8” in price-endings in China, and how this affects price-setting.

Figure 1 above, shows the transition matrices of price endings. We find that “8” and “9” are favoured as the destination of price adjustments in China. Sellers may set the endings using other digits at the beginning but learn to use the lucky ending digits after. However, sellers in the US and UK datasets are not significantly impacted by the Chinese numerology (see white bars in Figure 1). Only price points are prevalent in these countries. Once the basic facts are established, we explore the relationship between properties of price-setting and the prevalence of superstitious prices and observe consistent results. The price-setting behaviour in China is significantly affected by superstitious pricing, whereas no similar evidence is found in the US and the UK.

BlueBEAR’s HPC service is critical when we are dealing with large-scale parallel computations. It would take several days to get descriptive statistics using personal computers, since we employ daily price quotes for nearly half a million products over three years. However, BlueBEAR, with high-performance multi-core processors, can finish this process in hours, significantly improving our efficiency.

BlueBEAR, with high-performance multi-core processors, can finish this process in hours, significantly improving our efficiency.

Moreover, BlueBEAR is powerful when we deal with regressions with tens of thousands of controls. The waiting can be annoying if you face a deadline for a conference application without the HPC service. We can run multiple regressions at a time using HPC. Besides, vivid visualization can be made to improve the quality of your research. In conclusion, do not hesitate to try BlueBEAR in your economic studies.

We were so pleased to hear of how Zhuangchen was able to make use of what is on offer from Advanced Research Computing, particularly to hear of how he has made use of BlueBEAR HPC and its many cores – if you have any examples of how it has helped your research then do get in contact with us at bearinfo@contacts.bham.ac.uk. We are always looking for good examples of use of High Performance Computing to nominate for HPC Wire Awards – see our recent winners for more details.