Cai Wilkinson is a Lecturer in the Centre for Russian and East European Studies who works with IDD in the State-building in Difficult Environments research group.

Talk of the possibility of violent conflict in southern Kyrgyzstan, which is part of the cross-border Ferghana Valley region, is not new. The so-called “Osh events” of 1990, when clashes between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks led to the deaths of at least 100 people, have often been invoked as a warning over the last 20 years when socio-political tensions are on the rise. Nevertheless, until very recently, the question that could be asked was why violent conflict had not occurred in cities such as Osh and Jalalabad.

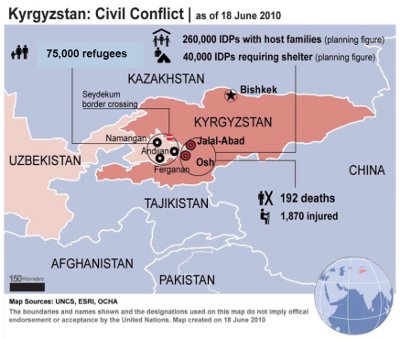

Map of Kyrgyzstan conflict, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 18 June 2010. For the latest updates see ReliefWeb.

All this changed on June 11, when large-scale violent clashes broke out in Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s southern capital located on the Kyrgyz-Uzbek border. To date, some 170 deaths have been officially reported as well as nearly 2,000 injured. The final death toll is likely to be considerably higher, since not all deaths are being reported before burial and as yet there are no figures for people listed as missing. In addition, entire Uzbek neighbourhoods, known as malhallas, as well as Uzbek-owned shops and businesses, have been systematically destroyed by arson attacks. Thousands of people, mainly ethnic Uzbeks, have fled the city and have been attempting to cross into neighbouring Uzbekistan, which has set up camps to deal with the sudden influx. Clashes also broke out in Jalalabad, resulting in at least two deaths and the destruction and looting of property.

Initial reports framed the violence as spontaneous inter-ethnic clashes that were the result of long-standing tensions between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. However, the most recent reports suggest that the clashes were triggered by five coordinated attacks by masked gunmen on June 10, leading a spokesman for the UN Commissioner on Human Rights to describe the violence as “orchestrated, targeted and well planned”. The aim of these attacks appears to have been to foment conflict between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz, thus causing massive socio-political instability and chaos, with the well-worn narrative of the inevitably of inter-ethnic conflict providing – from a Western perspective, at least – a simple and apparently logical explanation.

That this was achieved is already tragically evident. The questions that now need considering are threefold: who is behind the initial attacks, how further violence can be avoided, and where does Kyrgyzstan go from here?

The first question, I suspect, can only be answered speculatively. Unsurprisingly, given the ousting of Kurmanbek Bakiev, on April 7, many people are suggesting that members of Bakiev’s family or his supporters are behind efforts to destabilise the country in order to avenge their personal loss of power. Central to this interpretation is the role of Maksim, one of Bakiev’s sons, and Janysh, Bakiev’s brother, who were implicated in a tapped telephone conversation posted on YouTube on 19 May during which the speakers discuss hiring people to cause unrest and unseat the Interim Government that took power after Bakiev fled Bishkek. While this conversation appears to confirm many Kyrgyzstani’s opinion of the Bakievs, it is almost too neat an explanation and excludes the possible influence of other interest groups such as local criminal organisations and corrupt officials for example. Other theories about who is responsible for sparking the violence are similarly simplistic and neglect the complex web of dynamics involved.

Turning to how further bloodshed can be avoided, then here there are no clear answers either and the stakes are high in terms of not inadvertently exacerbating the situation. The Interim Government initially requested military aid from Russia, which was refused, as was a later request to the US. A state of emergency was declared and a partial mobilisation of the Kyrgystani army was authorised on June 12, but the violence continued for several days. As of the time of writing, the Interim Government has described the situation as “stabilising” and has refuted the need for peacekeepers.

This is arguably a premature and overly confident assertion, not least due to the challenges of dealing with thousands of displaced and traumatised people who have lost relatives and friends as well as their homes and livelihoods. The logistical challenge of providing humanitarian aid and assistance to those affected is far from inconsiderable, and the Interim Government would be wise to accept both aid and offers of assistance to ensure help is provided as rapidly and effectively as possible. If this can be achieved, then it is to be hoped that peacekeeping forces will not be required. However, at the moment this cannot be guaranteed, and the Interim Government would do well to consider how a peacekeeping mission would function.

Photo credit: Adam Oxford / nisuspi

Photo credit: Adam Oxford / nisuspi

Woman in Osh, September 2009

The uncomfortable question lurking behind the issue of deploying peacekeepers is that of the viability of Kyrgyzstan’s statehood. Descriptions of the republic as a “faltering state” emerged in late 2005 as mass protests continued to be held in the wake of the March 2005 overthrow of then-President Akaev. While the practical value of labelling Kyrgyzstan a “failing” or “failed” state is in many respects questionable, it does currently appear that the Kyrgyzstani authorities cannot fulfil one of the basic functions of the state, namely ensuring the safety of its citizens. If this cannot be achieved soon, then the mountainous republic’s prospects look bleak as the Interim Government’s already tenuous hold on power becomes even further discredited, intensifying and expanding the existing power vacuum.

The actions of all interested parties – both within Kyrgyzstan and internationally – in the coming days are likely to decide Kyrgyzstan’s short term fate to a large extent. What is desperately needed is visible leadership not only to provide aid and assistance to those directly affected, but also to challenge the narrative so often heard about Kyrgyzstan being an inherently divided society, be those divisions ethnic, regional, linguistic or political.

Violent conflict of this sort is not inevitable, even allowing for the “perfect storm” of circumstances that exist in Kyrgyzstan. However, it becomes far more likely when the checks and balances on personal and group interests are either non-existent or, as in Kyrgyzstan’s case, have been rendered increasingly ineffective by the very people who are supposed to ensure their presence. Re-establishing such safeguards is the fundamental task now facing Kyrgyzstan’s leaders.