Sumedh Rao is a research fellow in the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre. His areas of interest include governance, statebuilding, and aid policy in situations of conflict and fragility; political economy analysis; and aid architecture.

It is widely believed that people in developing countries need well-functioning states. Only well-functioning states can meet the needs of their people and achieve development objectives such as the MDGs. Therefore, development agencies and international organisations are now focusing squarely on “state-building”: improving state capacity, institutions, and legitimacy. However, there are a range of conflicting views about what constitutes an effective state, and the best way to achieve it.

The state-building model commonly employed by the international community aims to build a ‘responsive’ state. This involves developing reciprocal relations between a state that delivers services and social and political groups who constructively engage with it. An ‘unresponsive state’, on the other hand, is characterised by rent-seeking and political repression. State-building by the international community is undertaken by supporting the legitimacy and accountability of states through democratic governance (holding elections and constitutional processes), economic liberalisation/marketisation, and strengthening the capacity of states to fulfil their ‘core functions’ in order to reduce poverty.

What are the ‘core functions’ of a state? Though there is consensus that a resilient state must perform ‘core functions’ there is little consensus as to what these are. DFID, for example, differentiates between state ‘survival’ functions such as security and rule of law, and ‘expected’ functions – functions which help meet public expectations and ensure state legitimacy. Both are considered essential to generate a positive state-building dynamic. Lists of ‘core’ functions tend to include items such as: a monopoly over the legitimate use of force; revenue generation; safety, security and justice; basic service delivery; and economic governance.

Photo credit: Walt Jabsco

Photo credit: Walt Jabsco

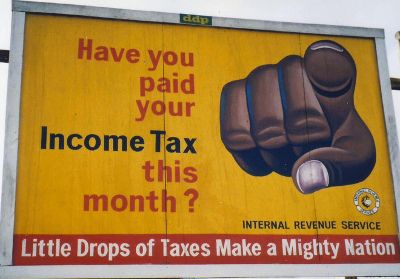

Have you paid your income tax? Billboard in Accra, Ghana.

Political settlement is often considered a requirement to allow security and stability for further state-building. It can be described as a forging of a common understanding, usually among elites, that their interests or beliefs are best served by a particular way of organising political power. Justice, security, and the rule of law are often considered prerequisites and allow for the enabling of economic and social development. Though many argue that economic recovery is a vital aspect of state-building in fragile states, opinions vary on the appropriate approach. Neoliberal policies such as macroeconomic stabilisation, reliance on the market and private sector development have the potential to undermine state legitimacy. They may hinder policy choice and the ability to win the loyalties and confidence of citizens. Others argue basic growth in productive activities such as credit programmes, infrastructure, and extension service, are a necessary condition for developing a tax base and therefore central to state-building processes. Taxation may allow better accountability to its citizens and in turn legitimacy. Despite this it is often overlooked by donors, in part because reforming tax administration is a highly complex and ultimately political undertaking. In general, one of the key challenges for donors is how to move from short-term projects, which often raise expectations and disappoint later, to more sustainable, long-term and state-lead economic recovery. A balanced strategy which combines emergency employment, income generating activities (including private sector development), and the creation of an enabling environment through legal and regulatory reforms, is necessary to support more durable forms of economic growth.

Photo credit: Tom Maruko

Photo credit: Tom Maruko

Protesters in Nairobi against salary increases for Members of Parliament, July 2010

State legitimacy is important but poorly understood. Recent research suggests that people’s ideas about what constitutes legitimate political authority are fundamentally different in Western and non-Western states. Non-Western states typically have competing political authorities (both traditional and non-traditional) vying for legitimacy. Legitimacy derives from four sources: input or process, output or performance, shared beliefs, and from international legitimacy. These different sources of legitimacy interact and no state relies on a single source of legitimacy. Local institutions and traditional authorities are often resilient, can endure state failure or collapse, and determine the everyday realities of poor people, particularly in remote or peripheral areas beyond the state’s reach. At the same time they may themselves perpetrate violence, vulnerability, or predation.

Donors need to balance the top-down focus on institution building with the strengthening of bottom-up access to institutions and accountability and promote active citizen participation. Social exclusion can be countered through supporting opportunities for enhancing excluded groups rights and their participation in governance. Gender roles and relations can determine opportunities and obstacles to state-building. Not focusing on gender early on can entrench systems that discriminate against women which are much harder to challenge later.

Decentralisation is supported on the basis that it can bring government closer to the people and acts as a means of increasing voice and representation. The ‘social contract’ may be easier to achieve in subnational governments which can better integrate regions and minorities into polities. The creation of multiple arenas of contestation for power through local government can avoid potential conflicts from ‘winner-takes-all’ situations. There is, however, scant evidence that the intended benefits of decentralisation have materialised, and it can be used simply as a tool for elites to extend their personal control or the control of government over the regions. Many studies have found that informal political institutions can subvert the decentralisation processes in fragile states and some caution that the relationship between state resilience and decentralisation is not yet well understood.

There are several inherent tensions and contradictions in state-building. This can be between external assistance and the need to develop local ownership, between universal values and local expectations, and between short-term imperatives (such as elite bargains) and the development of longer-term state institutions. Donors need to reconcile the need for long-term but not open-ended engagement, ensure policy coherence and divisions of labour within and between donor governments and agencies, and be mindful that aid instruments do not undermine state legitimacy.

For a summary of some of the best literature available on these issues, see the following GSDRC helpdesk reports:

For further reading, please visit our document library, or see the GSDRC topic guides on Fragile states and Conflict.