Heather Marquette is Senior Lecturer in Governance in IDD. Her areas of research include comparative politics; political development; African politics; state-building and governance in difficult environments; corruption, good governance and ‘moral politics’; donor approaches to anti-corruption reform; discourses on citizenship; and applied political analysis. She directs IDD’s International Development (Governance and Statebuilding) programme and is the academic director of the Governance and Social Development Resource Centre.

The UK’s Independent Commission for Aid Impact issued a report yesterday on DFID’s Programme Controls and Assurance in Afghanistan expressing strong concerns about DFID’s control over its programmes and resources in the country, and about corruption in particular. ICAI’s assessment is that this work is ‘Amber-Red’, which means that although it provides some evidence of value for money, there are big challenges and significant improvements need to be made. The report concludes:

DFID manages its programmes in Afghanistan in exceptionally difficult circumstances. It has a highly committed, respected and experienced senior team and a professional reputation amongst other organisations working in Afghanistan. We found, however, that DFID’s financial management processes are insufficiently robust and that DFID does not give sufficient importance to identifying and managing risks in the design and delivery of its programmes.

A key concern is what the report calls ‘leakage’ – in other words, money that’s disappeared, presumably lost to corruption. The ICAI examined documents and conducted interviews with DFID staff, its managing agents and NGOs that work with DFID in Afghanistan, and found insufficient evidence that leakage is being accurately tracked by DFID or its implementing partners. Indeed, ‘fewer than 25% of organisations interviewed in the course of our investigation were willing to estimate the amount of leakage’. Estimates are unrealistically low, lower than the overall UK estimates for fraud in the public sector, and much lower than US estimates for fraud in Iraq and Afghanistan. What this is likely to mean is that estimates are being either optimistically or intentionally under-reported. After all, there are few incentives for accurately estimating fraud and corruption.

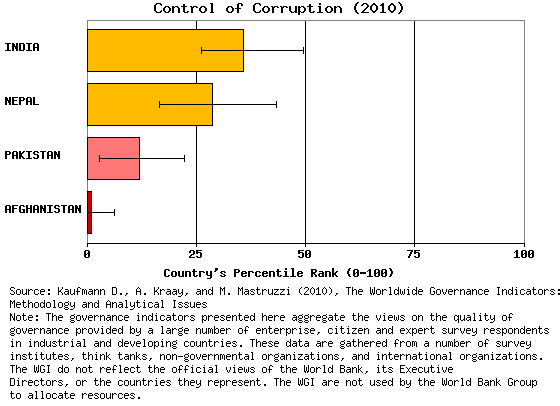

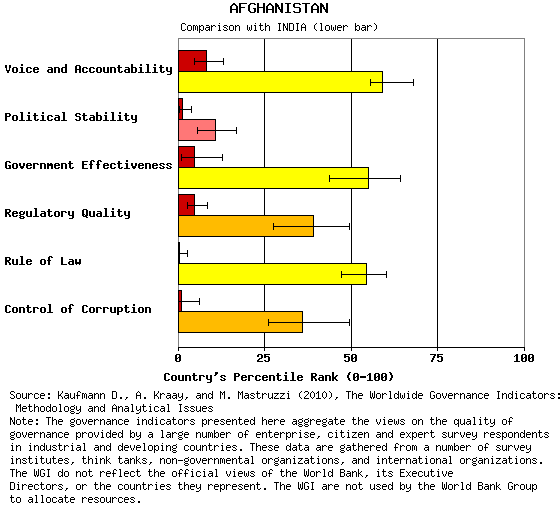

Afghanistan ranks 180th in the 2011 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, tied with Burma and above only North Korea and Somalia. In the 2010 World Bank’s World Governance Indicators, Afghanistan has a score of 1.0 for control of corruption, putting it in the bottom 10% of all countries. The same is true for the other WGI categories: voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality and rule of law. These are not just ‘exceptionally difficult circumstances’; they are among the most difficult circumstances anywhere in the world.

In April 2011, the Guardian (UK) journalist Madeline Bunting wrote: ‘It has always seemed to me that the big problem about increasing aid to “fragile states” was that it would be very hard to square with value for money. These are places that, by definition have poor governance and high levels of corruption’. What Bunting is talking about here is risk and the need to be more honest about this risk in order to make aid more effective.

I’ve written about this recently, with colleagues, and we concluded that:

Donors are currently grappling with resolving the apparent tensions between the dual goals of increasing aid to fragile situations while demonstrating value for money. Combining aid to fragile states with the results agenda through ‘good enough’ aid effectiveness, or a more nuanced interpretation of value for money is unlikely to be politically viable. Nevertheless, to avoid setting up expectations that they are unlikely to be able to fulfill or place unrealistic demands on country office staff, development agencies need to be more open about the challenges they are facing in pursuing the value for money agenda in fragile situations.

This isn’t simply a question of guidelines or procurement or increasing the number of financial management specialists on team; it is very much a political issue. In the UK context, open public debate about the risks inherent in working with fragile states are unlikely to be politically expedient, given the ‘broad but shallow’ level of public support for overseas development aid. As the recently published UK Public Opinion Monitoring Report states: ‘the majority of respondents think that tackling poverty at home takes priority over tackling poverty in other parts of the world. Aid is seen as a prime target for cuts in order to reduce the UK budget deficit. Over sixty-four percent of respondents were of the view that it is more important for the UK Government to tackle poverty at home than in other parts of the world’.

Given the ‘age of austerity’ and weakening trust in government, explicit UK government recognition of the possibility that public money spent on aid may be at risk would be unlikely to fly under the media radar and avoid the standard hyperbolic response. For this reason, there is unlikely to be a publicly accepted and advertised principle of ‘good enough’ aid effectiveness or value for money in fragile states. It is almost impossible for DFID to do what the ICAI has asked it to do, not just because the circumstances are so very difficult, but particularly for political reasons: is the UK public ready to hear that aid is inherently risky, despite the fact that the rates of return (measured in all sorts of ways) are often very high?

The World Bank has recently published its draft Governance and Corruption Strategy Update, known as GAC-II. The World Bank is the first donor I have encountered to state, in an honest and open way, something that should be common sense: development work is inherently risky, and working in deteriorating governance environments is even more so. This is, after all, simply common sense. Spending money in Kabul is of course riskier than spending it in New York or Paris or London. The Bank’s draft policy explains:

GAC acknowledges that development is a risky business and there is no way, other than not lending at all, to guarantee the absence of fraud and corruption. The Bank therefore will maintain the highest standards for managing and mitigating fiduciary risk. The Bank has articulated clearly its position on ‘zero tolerance’, which has two components. The first component acknowledges that the Bank has some ex-ante appetite for risk. The Bank recognizes that development initiatives in developing countries will inevitably encounter challenges and obstacles which present risks to its projects, and while the Bank seeks to mitigate these risks they will not be removed completely if the Bank is to maintain an ambitious approach to its governance work. The second component is an ex-post zero tolerance when it is shown that fraud, corruption or other malfeasance has occurred. In such circumstances the Bank will always and everywhere take action to address the problem.

The balance here of some ex-ante appetite for risk while maintaining an ex-post zero tolerance for fraud and corruption is spot on. What the Bank does here is not only articulate a sensible and appropriate policy for itself as an organisation, but it opens up the door for other donors, like DFID, to be able to say the same thing. All of this is absolutely a step in the right direction for establishing the sensible approach to managing risk that the ICAI report demands.

A different approach to risk doesn’t mean being tolerant of corruption, but it does mean that DFID staff and their implementing partners need to know that they will not be ‘punished’ if fraud is found, assuming they’ve done their job to the best of their ability in the circumstances with diligence.

The IATI report isn’t all doom and gloom for DFID, and there is evidence in the report recognizing real innovation. One approach that I’ve also studied is the way that DFID and other donors are working to help build integrity for provincial governors’ offices through a pilot Performance Based Governance Fund (PBGF). The PBGF provides funding to provincial governors – often (former) warlords – to support the running of their administrative offices, but money is disbursed based on performance, and this use of incentive-based payments is flagged up as good practice by the IATI report. The PBGF also incentivises integrity by publishing regular evaluations and adjusting budget levels according to performance. It emphasises transparency, capacity building, and citizen-state engagement, promoting statebuilding processes that address corruption. A study of the PBGF by The Asia Foundation found that the prominence of corruption as a political issue in Afghanistan meant that many governors have been able to use the PBGF to improve their reputations as good managers. Indeed, some who may have opted out of the fund were dissuaded from doing so by the risk of reputational damage. In other words, they learned that working with integrity pays political dividends and being seen to be corrupt carries a political cost. This is a very promising result.

DFID is hardly alone in grappling with how to protect taxpayers’ funds in some of the most difficult environments in the world, and it will need to figure out how to both protect staff who report fraud as well as how to deliver a politically viable message to the UK public on the real risks corruption poses in difficult governance environments. It also seems a bit unfair to shine the spotlight on DFID alone; after all, the same challenges apply to the MOD, the FCO and the DTI – all of whom spend taxpayers’ money in Afghanistan, but without independent watchdogs producing highly publicised reports.

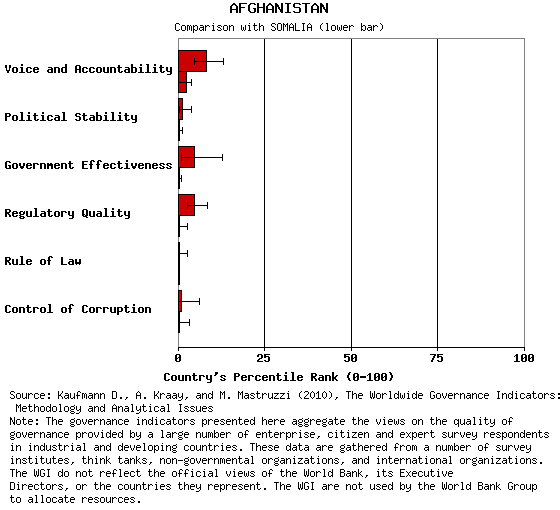

Ultimately, this comes back to corruption being the ‘c-word’ in aid, as former World Bank president James Wolfensohn said over 15 years ago. Until the domestic politics of aid change, it is hard to see how we’ll ever resolve the inherent tensions in delivering aid in difficult governance environments. And it has to be said, the IATI report shows some ‘green shoots’ of progress and innovation that may provide donors and others with clear models for how aid can best be delivered in environments as difficult as Afghanistan’s… or even worse.

Next stop, Somalia…