By Andrew Jolly, Doctoral Researcher

School of Social Policy, University of Birmingham

Food banks have been a constant item in the news of late, most recently after the Trussell Trust (the biggest food parcels provider in the UK) called on the general public to give extra donations of food for children over the school summer holidays.

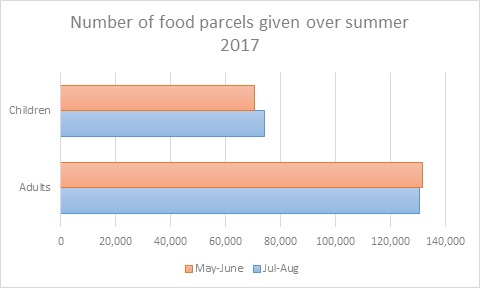

Trussell’s figures indicate that there was an increase in demand for food parcels to children in July of last year, which coincided with the start of the school holidays. This increase is likely a result of low income families, who rely on free school meals during term time, no longer able to afford an adequate diet for their children over the summer break.

Source: Trussell Trust

Professor Greta Defeyter from Northumbria University has estimated that feeding children over the holidays could add between £30 and £40 per week in outgoings per family, and the All Party Parliamentary Group on Hunger calculates that ‘holiday hunger’ may effect up to 3 million children. This is a particular concern at a time when food banks are reported to be struggling to cope with their regular demand and in some cases facing danger of running out of food to distribute.

Although many have, quite rightly, described the rise of food banks and holiday hunger as a national scandal, and a collective failure of welfare systems to meet people’s basic needs, there have also been attempts to alleviate holiday hunger on a local scale. One example is through holiday clubs such as Birmingham’s holiday kitchen. Holiday clubs provide structured collective provision of food and other activities for children and families during the school holidays, and although there is currently very little research into their impact, early indications suggest that they can be effective in reducing household food insecurity.

Holiday clubs are a very contemporary response to the growth in food insecurity in recent years, driven by the impact of austerity, benefit sanctions, universal credit and the hostile environment for undocumented migrants. However, such initiatives are far from being a uniquely 21st century phenomenon, holiday clubs have clear resonances with attempts to alleviate food poverty in the past.

The ‘British Restaurants’ of the 1940’s are a little known response to widespread food poverty amongst bombed out urban populations during the Blitz and the immediate post-war period. British restaurants were organised and run by local authorities but funded by central government. They were designed to feed large numbers of food insecure people quickly, nutritiously and cheaply. The British Restaurant network was extensive, at its height in 1942, there were 2,119 British Restaurants, serving 619,000 meals a day.

Source: Atkins (2011)

In contemporary terms, that is five times the current number of foodbanks in the Trussell Trust network. By and large these restaurants were popular with the public, and continued after the end of the war, even being put onto a statutory footing with the Civic Restaurants Act in 1947, with many surviving well into the 1950’s.

So why were they popular, and what can contemporary holiday clubs learn from the experience of British Restaurants? There are perhaps three points we can learn from them. First, unlike previous attempts at collective feeding, British Restaurants were emphatically not ‘soup kitchens’ with the connotations of charity and of the workhouse. Instead, they were indeed restaurants, which were open to all, and where people paid for cheap nutritious subsidised meals – there was no stigma in using a British Restaurant. Second, they were pleasant, homely places to eat. Thought was put into the décor and environment, many restaurants had artwork on the walls, and some even had live music. Finally, despite the wartime shortages in food, attempts were made to make the food both nutritious and varied. The British Restaurants in Birmingham offered a minimum choice of five meat dishes, five vegetables and five desserts, and attempts were also made to cater for regional differences in taste with different menu suggestions for different areas of the country.

British Restaurants were successful because they offered people something that they wanted, without shame, in an environment they wanted to be in, providing opportunities to meet, eat and socialise collectively – to be successful and to fight the current issue of holiday hunger, holiday meal clubs should do the same.