Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham

7.00pm on a Sunday evening is a sacred time for many viewers as they watch the valiant if eccentric, Doctor travel through time and space to battle mysterious aliens and injustice. I am usually found in a different corner of the living room during this time, but at a recent episode, I found myself completely gripped by the re-telling of the story of Rosa Parks. What is the power in sharing and telling stories of heroes like Rosa?

The ’Rosa’ episode was co-written by Malorie Blackman (a hero of mine and the first Black writer on Dr Who) and screened during Black History Month. It finds the Doctor and companions, landing in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955 the day before Rosa Parks’ famous refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger. The Doctor and companions are battling the villainous Krasko who, by stopping Rosa’s bus protest, hopes to put a stop to the Civil Rights Movement. However, although she outwits Krasko, it is not the Doctor who is the hero of the story. In fact, at the crucial moment on the bus, the Doctor says, “We have to not help her.” Rosa Parks is the one who takes a stand against the entrenched racism of Montgomery, without the inspiration or help of the Doctor and friends. It is Rosa who is credited at the end of the episode with changing the world.

The use of heroes and moral role models is a key feature of character education, particularly when there are concerns that children today draw their role models from unworthy celebrities (Kristjansson, 2006). Bandura (1968) found that a considerable amount of learning takes place through a process in which children learn behaviours, attitudes, values and beliefs by observing others and the consequences of others’ actions. By watching Rosa’s story, children observe her virtues – her sense of justice, her courage, and her resilience and the consequences of her actions. As the episode closes, the Doctor tells her companions that segregation on buses ended in 1956 as a result of Rosa’s actions and the Civil Rights Movement that she was a key part of.

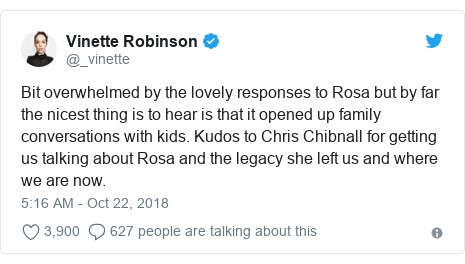

Online, the ‘Rosa’ episode was widely praised for its accurate portrayal of Rosa’s story and for opening up discussions about Rosa and her legacy. The actress, who played Rosa, tweeted:

The question is, how do we, as parents and educators, effectively use these powerful stories and role models to support character education? From an Aristotelian perspective, the emulation of role models requires us to identify the virtues that are worthy of imitating and why they are worth developing. We need to explore the virtues that Rosa showed in her life rather than just holding her up as a worthy role model. This can easily be done through discussions about what type of person she was rather than just the actions that she did. This will allow children, to apply the virtues that Rosa demonstrated to their own lives and situations rather than just looking up to someone else.

Role models and their stories are a powerful way for children to see virtue in practice and can inspire them to develop their own character, becoming the hero of their own story. Recent news articles about a Ryanair passenger who demanded that a black woman was moved from next to him brought the reality sharply into focus. Although we have come far from 1950s Alabama, there is still a long way to go and children will have plenty of opportunities to put lessons from Rosa’s life into practice.

References:

Bandura, A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kristjansson, K (2006) Emulation and the use of role models in moral education. Journal of moral education 35:1 p.37-49

Sanderse, W (2013) The meaning of role-modelling in moral and character education The Journal of moral education 42:1 p.28-42