By Professor Jane Martin, Director of Domus Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Histories of Education, Executive Editor of Educational Review

School of Education, University of Birmingham

On the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action for the empowerment of girls and women everywhere, the theme for International Women’s Day for 2020 is #Each for Equal.

Today, UN Women is bringing together change-makers for ‘Generation Equality’. This blog celebrates two women who shared a sense that social change was possible and acted upon that belief. They were not at the centre of power but were advocates of a praxis that involved reforming institutions to change the trajectory of political consciousness in 20th century England.

Inspired by the British socialist William Morris, the working-class Mary Bridges Adams (1855-1939) from South Wales, taught in Birmingham and Newcastle, married a fellow traveller, had a son and settled in London. There she joined the Gas Workers Union (saying she was a gas worker on the platform and a general labourer at home) and in 1897, with the support of the Royal Arsenal Co-operative Society, won a seat on the London School Board. The capital was a city of children, and this was a position of responsibility on what was then the world’s largest educational parliament.

Between 1870 and 1902 British school boards were responsible for the construction of universal basic elementary education. Ratepayers elected them every three years by secret ballot, and women could vote and stand for office. Multiple voting and the possibility of giving all your votes to one candidate, favoured the representation of electoral minorities, in this case, women and working people. Gendered social conventions meant that women were more likely to have/be given leadership in political decision-making by championing issues such as the education of girls and children’s health and welfare.

Feminists Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (Britain’s first home-trained woman doctor) and Emily Davies (co-founder Girton College, Cambridge) topped the polls in Marylebone and Greenwich when Londoners first went to the polls in autumn 1870. Ten years on, women constituted 18% of the membership. Women’s representation in Parliament did not match this until 1997, following the Labour Party’s adoption of all-women shortlists (1993-96). The 2019 General Election returned the highest number and proportion of female MPs ever recorded: 220 (34%) of 650 MPs are women. This continues the trend of increasing female representation in Parliament but still less than the 35% in London local government in 1952.

Mary Bridges Adams spent seven years as one of 55 members of London’s School Board. Campaigning for the introduction of free school meals, in her first speech she told her upper-middle-class opponents they could not possibly imagine what it was like to be poor. Challenging the practice of educating children according to their social position, she was against ideas of ‘merit’ and ‘meritocracy’ associated with building a scholarship by which the one ‘clever’ child in a big group may benefit (socially, culturally and economically), while the majority do not.

In 1900 she set up the National Labour Education League aimed at the creation of a comprehensive national education service, secular and free, with equal funding per pupil and school welfare services. All funded through the restoration of charitable, educational endowments (money, buildings and land) which she argued had been stolen from the poor through legislation passed by a parliament composed mainly of former public schoolboys.

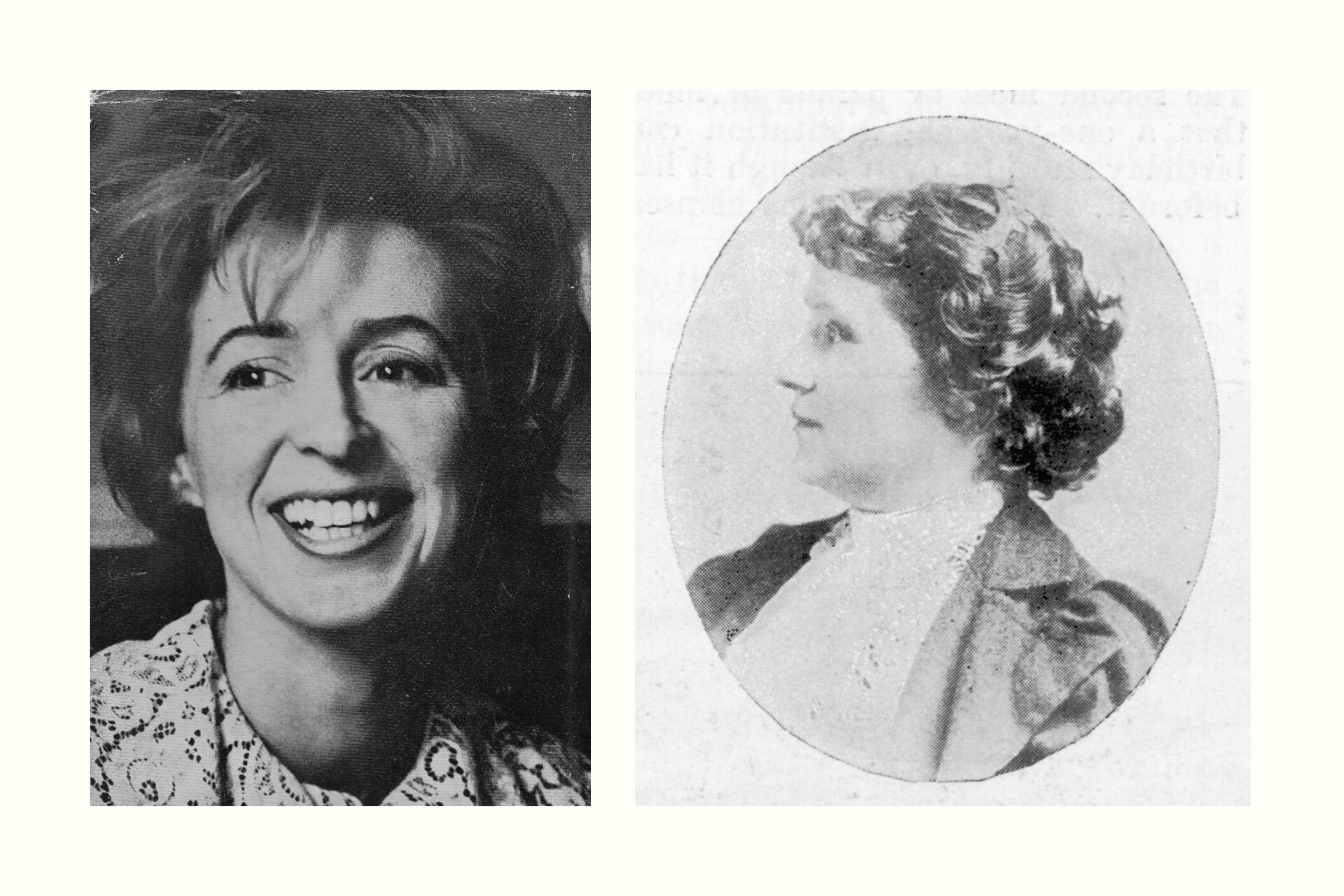

Last October, I went on a trip across the Atlantic to find facts and unearth information in the process of telling another woman’s life. That woman is Caroline DeCamp Benn (1926-2000), the American biographer and fiction writer, famous in education and political circles for her commitment to the development of a comprehensive school system.

Caroline Middleton DeCamp was born on 13 October 1926, the eldest child of Anne and James, a Cincinnati lawyer. Her paternal ancestors travelled west by wagon train in the 1800s. They included a circle of brothers who met President Lincoln and helped build Cincinnati: known not only as the ‘Queen City of the west’ but ‘Porkopolis’ – the major meatpacking centre of pigs. Benn’s maternal great-grandfather had migrated to the United States from Ireland and came to Cincinnati in 1876 where he later became a prominent Republican politician and manufacturer of patent medicines.

Benn was educated in the private schools of Cincinnati, Westover School in New Hampshire, Vassar College and the University of Cincinnati. While at Vassar Caroline organised a great arts conference of which she was very proud, bringing together lots of artists from all over the eastern United States. In the summer of 1948, she attended a summer school in Oxford, England, where she met Tony Benn over tea. Days later, knowing she was about to return to America and he might never see her again, he asked her to marry him on a wooden bench near an Oxford memorial (later, he bought the bench from the city council for £10 and installed it in their garden).

They were married in Caroline’s home town and had four children, all born in the 1950s. Meanwhile, Caroline completed an MA at University College London (while she was expecting her first child) and her husband entered national politics, serving as a Labour minister in the 1960s and 70s. The couple made their home in Holland Park Avenue, ten minutes’ walk from Holland Park, the new comprehensive secondary school that opened in west London in September 1958 and which they chose for their children’s education. Caroline became a governor of Holland Park, serving in total for 35 years.

Caroline Benn dedicated her life to seeking a new educational dispensation for the mass of British working-class children. In 1964, Labour leader Harold Wilson’s vision of a New Britain captured the zeitgeist of the period. Amid assertions that British society was still too class-ridden, he denounced the selective education system as having failed the country. He promoted the comprehensive secondary school as a way of equalizing opportunities. Outside Whitehall, those wanting to accelerate change launched the Comprehensive Schools Committee on 24 September 1965. Supporters and critics alike acknowledged the moving spirit was Information Officer Caroline Benn.

So vast was Benn’s knowledge that, in the 1960s and 1970s, politicians and policymakers would telephone her for information and she was co-opted as an expert member of the Inner London Education Authority. Across three decades, she contributed numerous articles for education journals besides editing Comprehensive Education the journal of the Comprehensive Schools Committee.

She co-authored the two most thorough investigations of the comprehensive movement, Half Way There, written with Brian Simon in the late 1960s and Thirty Years On, written with Clyde Chitty (then working at Birmingham’s School of Education) in the mid-1990s. She was also President of the Socialist Education Association and a member of the UNESCO Commission. Contemporaries lauded her energy, evidenced by her husband’s comment that she did more evening meetings than he did.

A political wife who spoke up to take a stand and mobilise, not only to define herself as an individual and transform the conditions of her own life but those of others.

Some say that biographies are better if the biographer has a particular affection for their subject. In so much as I know Caroline Benn through my research, I do like her. A tenacious campaigner who never lost sight of her principles, she belongs to a long line of women struggling to make their political voice heard. We can think of American examples like the reformer Jane Addams who set up a women’s settlement in Chicago, Hull House, in 1889, and cleared a space for a new public role for women. In Britain, the Women’s Co-operative Guild and the Fabian Women’s Group sought to combine an awareness of class and gender in campaigns that spanned work and community.

This is not an argument for alternative heroines. It is, instead, a case for new ways of seeing the same historical space and fostering greater awareness of women’s place in education and politics. History matters, and we need to bring out the contemporary relevance of 20th-century women promoting democracy and education in British schools.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the warm welcome from the staff in the Cincinnati History Library and Archives who helped me find my way around the materials in their collections and the ongoing support of the Benn family.

- Caroline Benn: a comprehensive life, 1926-2000. British Academy/ Leverhulme Award Number: SG1311085.

- Mary Bridges Adams, 1897 @ Mary Evans Picture Library.

- The Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati History Library and Archives

References

- Benn, C. (1962) Lion in a Den of Daniels. London: William Heinemann.

- Benn, C. and Simon, B. (1972 edition) Half Way There: Report on the British Comprehensive School Reform. Harmondsworth. Penguin.

- Benn, C. (1997) Keir Hardie. London: Richard Cohen.

- Benn, C. and Chitty, C. (1997 edition) Thirty Years On: is comprehensive education alive and well or struggling to succeed? Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Martin, J. (2015) ‘Building Comprehensive Education: Caroline Benn and Holland Park School’, Forum, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 363-386.

- Martin, J (2013) Making Socialists: Mary Bridges Adams and the Fight for Knowledge and Power, 1855-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Martin, J. (2013) ‘Gender, education and social change: a study of feminist politics and practice in London, 1870–1990’, Gender and Education, Vol. 24: No. 1, pp. 56-74.