In this case study we hear from Edwin, a PhD student in Biochemistry,who has been using BlueBEAR to evaluate the effectiveness of different Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation protocols at assigning structural information to Ion Mobility data

Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS), Traveling Wave Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TWIMS) and High-Field Asymmetric Wave Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) are analytical techniques that can discern molecules based on their distinct geometrical structures.

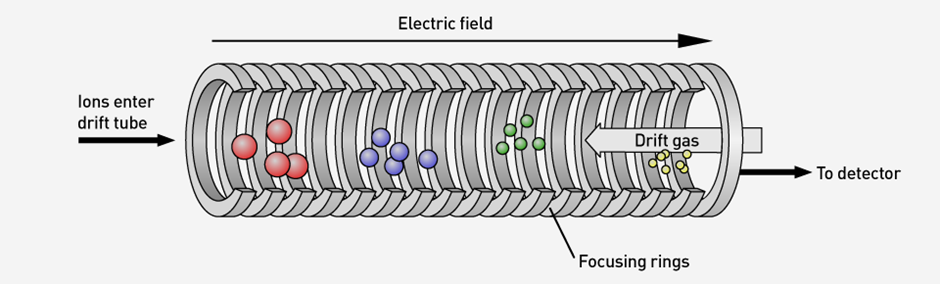

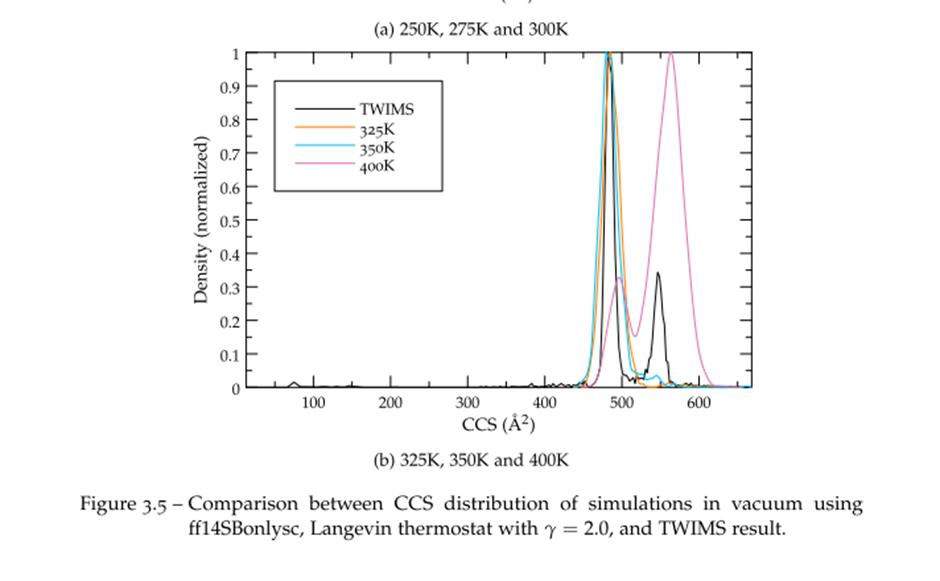

Since ionised molecules are moved through a gas (usually an inert one) while under the influence of some form of electric field (Fig. 1 shows the principle of operation of IMS), how often they collide with gas molecules, and hence how fast they can travel, depends on their Collision Cross Section (CCS), which is a characteristic closely related to their structure. However, determining the specific structure that corresponds to a particular signal given by the instrument requires the assistance of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations and CCS calculations. The aim of my PhD project is evaluating the effectiveness of different MD simulation protocols at assigning, with the highest possible degree of certainty, a structure to a signal obtained experimentally. In this context, a simulation protocol refers to the specific MD simulation technique employed and the particular values given to its parameters.

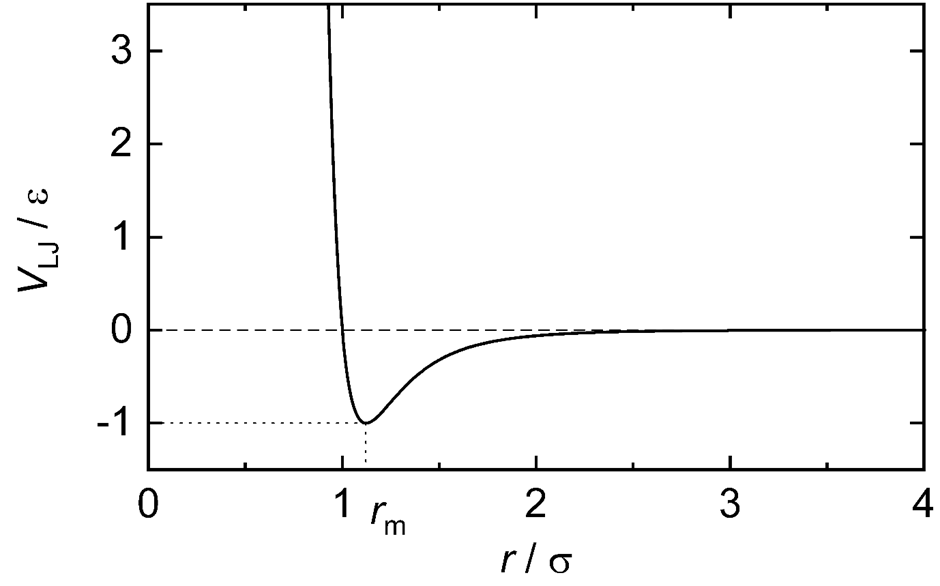

The interactions between atoms of a molecule can be simulated using different approximations, with varying degrees of accuracy. The approaches can be broadly classified in two groups: those using Molecular Mechanics (MM) and those using Quantum Mechanics (QM). In general, MM-based MD simulations model bond interactions, i.e. bond length, angle and torsion angle, using Hooke’s law. That is, they are regarded as exhibiting a similar behaviour to a mass attached to a string. In this way, a bond length or angle smaller than a preestablished equilibrium value means that the atoms involved will be subjected to a force acting to increase those magnitudes, just like a mass that compresses a string. On the other hand, if a bond length or angle is greater that the equilibrium, their atoms will experience a force decreasing those magnitudes. A similar force will act on atoms constituting a torsion angle if it deviates from its equilibrium point in either direction. Non-bonded interactions are accounted for by MM too. Van-der-Waals interactions are modelled using what is called a Lennard-Jones potential, which behaves as shown in Fig. 2. Coulombic interactions are calculated as if each atom were a point charge located at the centre of the atom.

Quantum Mechanics techniques do not attempt to model atomic interactions using classical mechanics systems. Instead, they implement different algorithms to numerically solve the Schrödinger equation of the molecule. This permits greater accuracy and the ability to model electron transfer between atoms, and therefore bond formation and destruction. However, these techniques are much more complicated and computationally expensive that Molecular Mechanics.

Carrying out all these calculations is only possible using a massively parallel system like BlueBEAR, as I can use tens of years of CPU time in a given month

The methodology widely accepted to calculate Collision Cross Section (CCS) is the Trajectory Method. It involves simulating collisions of gas molecules with the molecule of interest. These calculations are performed in a similar fashion to Molecular Mechanics ones, although with additional approximations to decrease the computational cost. However, many thousands of collisions of gas molecules following different random paths need to be simulated to obtain a good approximation to the real CCS.

BlueBEAR has been essential for my PhD project given the scale of my computational requirements. My research methodology requires performing many simulations employing a combination of different techniques and parameters that need to be evaluated. Additionally, from each of them, thousands of structures are extracted and their CCS calculated. Carrying out all these calculations is only possible using a massively parallel system like BlueBEAR, as I can use tens of years of CPU time in a given month.

We were so pleased to hear of how Edwin was able to make use of what is on offer from Advanced Research Computing, particularly to hear of how they have made use of the BEAR compute and storage, – if you have any examples of how it has helped your research then do get in contact with us at bearinfo@contacts.bham.ac.uk.

We are always looking for good examples of use of High Performance Computing to nominate for HPC Wire Awards – see our recent winner for more details.