by Professor Francis Davis

The other day, the Bishop of Durham expressed concerns that for poor families the time lag between applying for social security payments and receiving them is so great that hardship is enhanced. As though listening the government announced that the roll out of its flagship Universal Credit scheme was being stalled. Meanwhile, the new Conservative MP for Devizes, Dr Danny Kruger, in his maiden speech, called for the rediscovery of historic Christian ‘social infrastructure’ after Brexit. As the bells rang out on our last days of conformity to European social standards I could not help thinking: where are such debates headed?

The Bishop of Durham, of course, had a real point. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is now so large and centralised as a department of state that it really struggles with service to client groups where an error of only two days’ consequence can have devastating impacts. As a carer, I often spend hours on the phone to London, then the North West and then the North East chasing the different places in which correspondence has been scanned, read, acted upon and responded to. If a GP writes to assessors outside a standard form it can trigger automatic rejection of a claim. If a ‘medically qualified’ assessor is a podiatrist they can still be expected to consider cases involving medication designed for the other end of the body. In my experience staff are rarely unhelpful but too often are unsighted of a whole case – or each other. It’s strategic too: as a ministerial advisor at DWP I suggested to its procurement teams that they use the Social Value Act to create openings for disabled people through their estates and catering functions. Perplexed managers, trained only to score short term cash gains in the purchasing process, wondered out loud what such an aspiration had to do with government in general, let alone the department charged with disability inclusion in the workplace.

The history here is important. The first employment exchanges were trialled by volunteers experimenting from Toynbee Hall in London’s East End. Among those activists were the future Archbishop William Temple, a future Prime Minister Clement Attlee and the future London School of Economics Director and architect of the first welfare state Sir William Beveridge. They judged that social solutions needed scale if they were to be in any way helpful to those without a safety net. A few, such as Michael Young who had written the 1945 Labour manifesto, cautioned against this ‘biggism’ but others grasped its perceived economies of scale as essential. Ironically, hierarchical denominations actually seemed to thrive on equally hierarchical departments of state because, on balance, their leaderships were often mutually clubbable.

However, contrary to those energetic voices regularly now found in local micro-projects that claim Christian contributions were then ‘ripped up’ and crowded out by the state, they were not. Neither did they lose their zeal. Indeed, they were always powerfully present and in due course sought to refresh the original Temple/Beveridge/Attlee settlement by calling mass produced support into question.

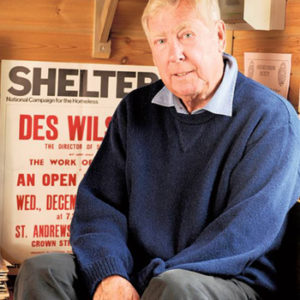

The second welfare state and society emerged, during and after the 1974 oil crisis, thanks in great part to the profound skill of many in the churches and faith communities working in collaboration with wider civil society. At its heart were welfare rights, calls for flexibility and the recognition of women, disabled people and BME communities especially. Funding from the Quaker Joseph Rowntree Trust created a hub in Poland Street, Soho from where Frank Field launched the Child Poverty Action Group and the Low Pay Unit to revitalise what is now DWP. From here also came the Tory Reform Group. The Simon Community, Centrepoint, Cyrenians, the St Dismas Society and others combined to contribute the backbone of what became Shelter. Des

Wilson (see photograph) led this hub, and, resourced by a Jewish philanthropist, also founded the Freedom of Information campaign, the Campaign for Lead Free Petrol and Friends of the Earth. Each of these causes in turn landed groundbreaking legislation for transformational improvements ranging from the first legal duty for local authorities to care for homeless families, to credible housing benefits, to the removal of polluting toxins from our fuel, to the requirement of governmental transparency. It may not be until Alistair Redfern, then Bishop of Derby, played a crucial role in the development of Theresa May’s Anti-Trafficking legislation, or when Citizens UK trail-blazed the Living Wage that similarly systemic changes were as significantly shaped by faith-based innovators and their partners. Meanwhile, the hospice movement, Samaritans, Tearfund, CAFOD, Christian Aid and the much later National Citizens’ Service all had their roots in Christian leadership and networks.

One hopes that it is this tradition of Christian social infrastructure that Danny Kruger was celebrating rather than the more stretched days where faith-based gaps in care would leave those who had grown up in small towns such as Leigh, Blyth or Bassetlaw remembering the night-time cries of agony of cancer patients who could not afford pain relief. Despite pre-World War II parochial benevolence, and the moralising earnestness of the old Charity Organisation Society, before the welfare state British men would often arrive for national military service too malnourished to be acceptable as recruits; farm hands might typically expect a two-hour walk for support after an accident.

Today though there is a new wave of Christian initiatives claiming a profound ‘distinctiveness’, to be ‘filling a gap’ that has ‘been empty since 1945’ and which can claim to ‘add more value than (their) secular counterparts’. It is unclear, thus far, if these new entrants – often linked to new churches – are a return to a narrative that seeks to legitimate lost paternalisms, the beginnings of a new approach to systemic and collaborative social improvement, or a new movement more interested in its own self actualisation rather than fighting need and want.

And here is the conundrum: while the Bishop of Durham speaks powerfully and convincingly on the impact of DWP’s weaknesses, too often those who rely on such support have become so detached from the lives of churches and Christians for that conviction to be a core insight from congregational life. This too often sets up a class gap between not only churches and wider civil society but also between them and their inter-religious interlocutors. Meanwhile, some growing local churches have become so gathered from single class bases that they are at times now divorced from the places in which they could in fact act as anchor institutions. Furthermore, so compelling have some of their theologies of the ‘uniqueness’ of Christian service become, and so intense the insistence upon them as an entry point to volunteering let alone becoming a beneficiary, that they constrain collaboration and the possibility of change at scale alongside many who would be vaguely but not wholeheartedly sympathetic. The net result might be not that there is a renewal of social mission going on but that the demanding task of advocacy and the dirty work of ‘political love’ becomes outsourced to others while worthy souls get on with the ‘pure’ and polite stuff of being nice.

If this is the case, it would not be surprising if, as Bishops name the time lags and inflexibilities of the DWP that are in so many contexts becoming worse, there were a decreasing likelihood of spontaneous and vocal cries of support. No wonder either that at times Christian self-dramatising and self-legitimating calls to ‘new mission’ might convince talented, newly-arrived parliamentarians that ‘Christian infrastructure’ could take the place of good social policy and responsive departments of state or that they are as strong as they once were during the construction of the first and second welfare states. This is dangerous.

Until we take stock the risk is that, as Brussels fades into the distance, the Christian contribution to a richer weave of social justice could in fact be stuck. And as the government and others set out to build a third welfare state, so many who deserve social insurance, solidarity and mutuality will then stand at greater risk still of being washed from view despite the immensity of the words strewn all about them.

Francis Davis is Professor of Communities and Public Policy in Birmingham and Professorial Fellow in the Institute on Ageing Population at the University of Oxford. From 2004-07 he chaired the Observer 2007 Social Enterprise of the year, SCA care. From 2015-17 he was appointed by the Minister for Social care to the cross government Standing Commission on carers and in 2017 he was appointed an external ministerial advisor at DWP. From 2016 to 2019 he chaired patient hearings under the Mental Health Act.