Rebecca Riley outlines some of the misconceptions around the use of the Green Book.

As part of the Y-PERN conference held recently, I had a slot on a session about the Green Book, partly because I chair the Green Book User Network Steering Group, but also because City-REDI does a lot of work helping partners develop business cases on amounts over £150m in the last few years. The conference was also held as the furore, especially in the West Midlands, of the Levelling Up round 2 allocations were announced.

In the session at the conference, we listened to excellent insight from West Yorkshire and South Yorkshire Combined Authorities and this blog summarises some of the thoughts, comments and questions raised.

Many people don’t know what the Green Book is or see it as a mythical set of difficult checklists, processes, and hoops to jump through to get a project/programme/policy funded. There is a perception that this work can only be done by economists or consultants. When funding isn’t approved it’s often the Green Book that is blamed, but as the IMF’s Public Financial Management blog says “don’t blame the tools”.

As the book says it is “not a mechanical or deterministic decision-making device”. It provides a framework on how to spend public money, and how to provide the best advice to funding decision-makers, clarifying the public benefit, alternative options, and delivery of policy objectives.

Business case (or bid) writers need to see themselves as offering advice to decision-makers on which solution, solves a problem, in the most efficient and effective way.

If you come to use the Green Book with a ready-made idea, the guidance will not work as intended. The guidance is fundamentally about producing multiple solutions and ideas to solve a problem and working out which idea is the best, based on the objectives you have set. If you complain about the Green Book blocking or slowing thoughts, then you aren’t using it for the purpose it was set up to do. If you have one good idea, a solution looking for a problem, and you are using the Green Book as a tick box, you will hate it. If you have a problem, don’t know the solution, and want to try out multiple ideas and solutions you will love it.

What are the risks and criticisms?

One of the criticisms of the guide is its focus on the economic impact, which technically, has never been the case. It was conceived as guidance to balance economic, social, and environmental goals. But over time as government funding has focussed more on costs and economic returns, projects and programmes have in turn had strategic cases that look at this as the core objective. The guidance, however, has never mandated this. Economic and monetizable benefits are easy to monitor and therefore better to measure as outputs and outcomes that demonstrate the success of a programme.

The main finding from the Green Book review was the poor quality of the strategic case. This has been echoed by the National Audit Office (NAO), who highlights the need for the strategic case to be easily understandable so that effective trade-offs can be made; help prioritise cross-government objectives; and be measurable (where possible). Echoing that the function of the business case is to help decision-makers make good decisions. The NAO stated at the time “Government plans to invest heavily in programmes, with £100 billion expected investment in 2021-22 alone. For the government to secure best value from this it must set out clearly and logically what it wants, how to best deliver this and how it will show what has been achieved for the investment”.

We have recently seen issues with a lack of transparency of funding criteria or changes to funding whilst ideas are being formulated. This has led to a lot of bids not being successful based on the changed or unknown criteria. Large amounts of public money (£27m) have been spent on unsuccessful bids, our own estimates for the Community Renewal Fund echo these amounts with £3.3m just in the West Midlands on 110 bids. As NAO points out, the government needs to clearly set out what it wants, and what it wants to achieve, this will reduce waste in the system.

One of the biggest risks to developing good business cases is the time to develop your evidence base, identify challenges and properly assess the options. A key issue facing delivery organisations, Local Authorities, and the consultants who support them, is the simultaneous launch of multiple competitive funding programmes and the process implemented often requires full business cases. This puts a lot of strain on scarce resources to develop good quality business cases, anecdotally several consultancies were turning away work as they didn’t have the capacity, this includes City-REDI.

This leads to weaker business cases across the board, as places lack the skills, knowledge, and access to expertise to drive innovation in business cases to improve public policy, programmes, and projects. This is compounded by the lack of recent evaluations and competitive process that reduces the ability to collaborate across boundaries, learn from others and share good practice or bids that have failed to get funding.

Why is it hard to learn from others?

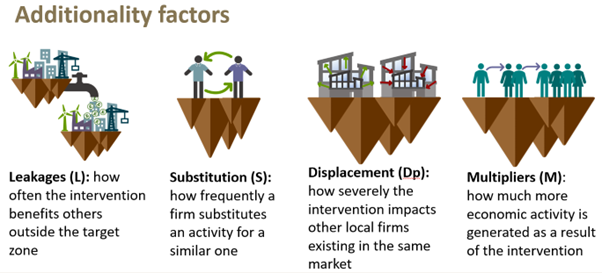

Last summer City-REDI did a review of successful business cases, the purpose of which was to gather case studies on how people have approached additionality in a business case to be able to share with partners. Additionality determines how innovative or exceptional an intervention is by assessing the achievement of desired outputs and outcomes over and above what would have occurred anyway under Business As Usual (BAU) conditions (known as the ‘deadweight’). It also considers factors that lessen the local impact of an intervention due to:

- leakage – how often the intervention benefits others outside the target zone

- substitution – how frequently a firm substitutes an activity for a similar one

- displacement -how severely the intervention impacts other local organisations existing in the same market

It may include multiplier effects (how much more economic activity is generated as a result of the intervention) that increase the impact on the local economy through rounds of supplier spending and consumption:

We utilised the Green Book and supplementary guidance as base sources and then looked for business cases for successful bids for Levelling Up round 1, Towns Fund, Future High Streets, and Transforming Cities Fund.

Based on the review, we identified 805 projects that were funded but only 11.7% had publicly available business cases. Of those, on average 44.7% didn’t mention additionality, a core part of the Green Book guidance on assessing bids. Of all the 94 bids we found only four had covered all additionality factors. Where they were mentioned, none used recent previous evaluations and most were the straight applications of the Green Book Guidance, which is outdated, although Treasury is working through updating all guidance following the new Green Book revisions.

What are the implications?

We have reflected on this as a team and without a more detailed analysis it is difficult to assess why this is the case. However, this would suggest it isn’t the guidance that is the problem, but the scoping, specifying and assessment of funds and the ability of applicants to utilise the guidance.

However, we don’t have an accurate picture of quality and therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions, as we don’t have access to all business cases, their evidence base or the assessment. These general findings do reinforce the findings of other research City-REDI has conducted. Potential reasons for the lack of application of the Green Book guidance would need further investigation but could be:

- There is a lack of skills and expertise in developing business cases both in central government and local and regional government (a topic discussed in Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington’s latest book – The Big Con)

- There is a lack of capacity and will (due to bid fatigue) to deliver good quality bids in an environment where there are constant new programmes and competition

- As people don’t share their bids (as competitive) there is a lack of learning from best practices and good examples or transparency in approach

- This is further impacted by the lack of evaluation and reflective learning in the system

- In defence of the Green Book, the guidance isn’t being applied as extensively as it should be

In essence, our review shows that the Green Book guidance cannot be responsible for Levelling Up funding decisions.

Lessons for the future

The use of competitive processes should be used wisely to achieve specific outcomes. The challenge is to design and construct a process that optimises the social efficiency of the final allocation at a strategic level. The guidance in fact covers competitive funds (section 5.13) and states “To achieve such an efficient use of public resources the allocating authority should define, in consultation with potential bidders, the overarching objectives that the bidding process is designed to support”. Bids should initially be completed to the outline business case (OBC) focusing on the agreed objectives, taking account of costs, benefits, unquantifiable features, risks and uncertainty. Allocations are then made provisional, until the completion of a full business case (FBC). This reduces wasted effort. The guidance also goes on to say in developing competitive processes, organisations should “weigh the benefit of competitive process against the administrative costs and potential impacts on the ability of bidding organisations to plan strategically”. It would therefore seem that the best course of action would be for funders to follow this guidance.

There does however need to be a mindset change for those bidding for funding, this isn’t about winning funding, it’s about explaining the problem you are trying to solve and giving decision-makers the right information to choose the best solution. We are setting out on a journey together to agree on a problem we must tackle, and how we can solve it, the business case is ultimately a record of that journey and those discussions.

This blog was written by Rebecca Riley, Associate Professor for Enterprise, Engagement and Impact, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

Everyone with an interest in improving social value should read this informative article about real world issues in allocating public resources better and the problems involved. Not the least of which is building a shared culture of understanding of best practice based on shared use of the guidance.