In June, Rebecca Riley, Anne Green and Des McNulty published a paper, Engaging universities in ‘Pride in Place’ and levelling up. In this blog we look back at the Universities and Region Forum: Universities, Pride in Place and Levelling Up policy briefing, on which the paper was based.

The Levelling Up White Paper from 2022 aimed to address the decline of ‘left-behind’ UK areas caused by community demoralisation and structural deficits. It called for deeper changes beyond cosmetic efforts, involving comprehensive policies, effective leadership, and collaboration with civic institutions and universities. The goal was to increase local pride and close the performance gap by 2030.

Understanding the Root Causes of ‘Left-Behind’ Places

The Levelling Up White Paper was rooted in a spatial deficit model – the proximate causes of places being ‘left-behind’ are a combination of community demoralisation and the lack of effective leadership, to which ‘pride in place’ is seen to be the antidote. Past remedies have included sprucing up town centres and public buildings – based on the ‘hanging baskets’ theory of change whereby a small amount of highly visible, cosmetic short-term investment (Shaw 2022) leads to a sea-change in attitudes of local people and external perceptions of a place.

However, the White Paper acknowledged that being ‘left-behind’ is also attributable to a wider set of structural deficits. These include low productivity in most of the UK’s major conurbations outside London and south-east England; a half-life of long-term path dependency stemming from industrial job loss and closures, especially in towns remote from growth clusters or on the fringes of the main cities in northern England and the Midlands (Strangleman 2017); and population shifts with jobs and skilled workers leaving places that have become economically redundant or are isolated (such as peripheral rural or coastal communities in many parts of the UK).

Social Capital Depletion and Demographic Changes

Depletion of social capital can take various forms depending on circumstance, the most important of which is the out-movement of young ambitious people who are pulled to London and other cities by better educational opportunities and job prospects. In consequence, many towns and rural areas have higher proportions of older, less affluent and economically inactive people. The growth of remote working, housing costs and quality of life considerations have led to some people relocating away from the London commuter belt, where their purchasing power drives up prices, resulting in a lack of affordable housing for local families and young people, an additional push factor.

Many of those who remain are experiencing a loss of amenities and the fraying of the social fabric that previously allowed left-behind places to maintain themselves as viable communities – potent symbols of unwanted change include the replacement of stores by betting, payday loans and charity shops. Outside the more affluent and metropolitan areas of the UK, pollsters report many people feeling ignored and looked down on. Pressure on local services resulting from immigration and a perceived threat to the host culture and way of life were among concerns raised in places such as Wisbech in Cambridgeshire and Boston in Lincolnshire that voted overwhelmingly for Brexit.

In the 2019 General Election, disenchantment benefitted the Conservatives who were able to secure so-called red wall seats and strengthen their hold in other ‘leaver’ parts of England. David Goodhart’s analysis (Goodhart, D (2017), The Road to Somewhere) of the emergence of two value clusters: educated mobile people who value autonomy and fluidity and see the world from “Anywhere” versus more rooted, generally less well-educated people who prioritise group attachments and security and see the world from “Somewhere” is a simple framing of a complex process through which social cohesion is being eroded. Michael Sandel develops a different but related argument about the rise of populism and its corrosive effect on democracy in the USA (Sandel, M. (2020) The Tyranny of Merit).

Addressing Spatial Inequality Through Policy and Leadership

In left-behind places, lower levels of attainment and progression to higher levels of education is a vicious circle, leading to smaller proportions of graduates and other highly skilled people in their 20s and 30s, making it more difficult to retain and attract well-paid jobs (EPI 2022). Restricted opportunities available for upward mobility and the age-skewed population consequently found in many left-behind areas reinforce a tendency to hark back rather than look ahead. Resistance to change is not confined to poorer areas but in more affluent places it tends to be protectionist/ exclusionary (e.g., resistance to new infrastructure or housing) rather than a more generalised antipathy to change based on low expectations and/or prior experience of externally generated initiatives. Population movements towards cities and the increased diversity that comes with migration leads to cities being re-imagined and repurposed to meet the needs of incomers alongside existing residents, increasing multiculturalism, and creating a forward-looking mindset. This reinforces cultural and attitudinal divisions between cities, suburbs, and left-behind places.

Injecting dynamism and breaking this cycle of spatial inequality were the core aims of the Levelling Up White Paper. Still, it is not clear how the mission statement – to restore a sense of community, local pride and belonging, especially in those places where they have been lost – or the targets – by 2030, pride in place, increasing people’s satisfaction with their town centre and engagement in local culture and community in every area of the UK, with the gap between top performing and other areas closing – could have been delivered.

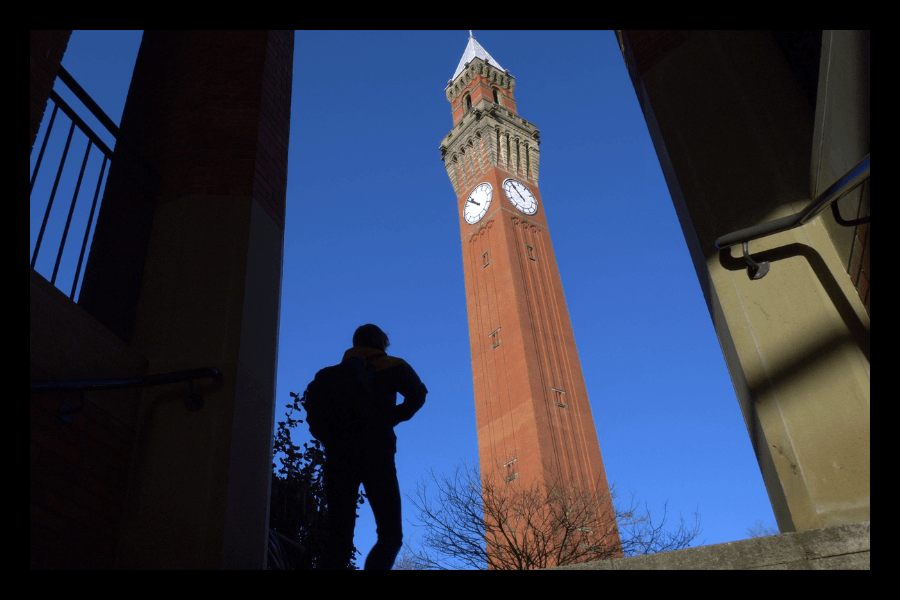

This blog was written by Eve Orford, former Digital Marketing and Communications Assistant at City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.