Professor Anne Green looks at the impact of the Covid-19 crisis and lockdown on the employment prospects of different age groups, focusing particularly on older workers and the challenges they face should they get made redundant.

Professor Anne Green looks at the impact of the Covid-19 crisis and lockdown on the employment prospects of different age groups, focusing particularly on older workers and the challenges they face should they get made redundant.

Introduction

Much of the policy response in the wake of Covid-19 has focused on the plight of young people. This is appropriate given the disproportionate hit they faced with the shutdown of specific sectors where they are concentrated (such as hospitality), their consequent particularly high rate of furlough and the implications of longer-term scarring of difficult transitions from education to employment.

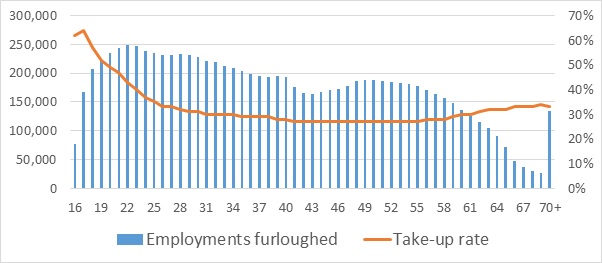

The diagram below based on data from the HMRC on claims received up to 31 July on the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme shows at the national level the number of employments furloughed by single year of age and the take-up rate (i.e. employments furloughed as a percentage of eligible employments). It is clear that in both absolute terms and the take-up rate young people aged under 25 years have been particularly hard hit.

The take-up rate is lowest at 27% for individuals aged between 41 and 55 years. The take-up rate increases from the age of 55 years and rises to over 30% for those aged 60 years and over.

The increase in older workers

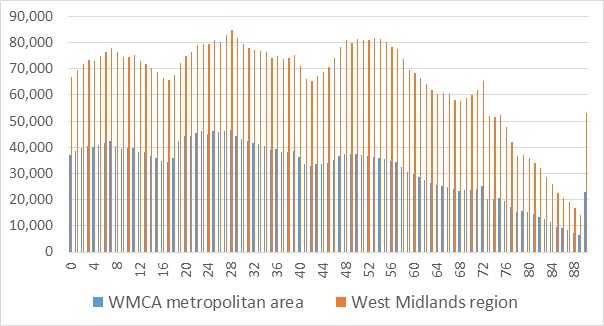

The older workers highlighted above were entering the labour market in the early 1980s recession. They are part of a large cohort as demonstrated in the chart below showing the age structure of the population in the West Midlands region based on 2019 data from the ONS Mid Year estimates of population. The WMCA metropolitan area has a younger age profile than the region but nevertheless, the relatively large numbers of people in their fifties and early sixties is evident. (By contrast, current school leavers are part of a small cohort).

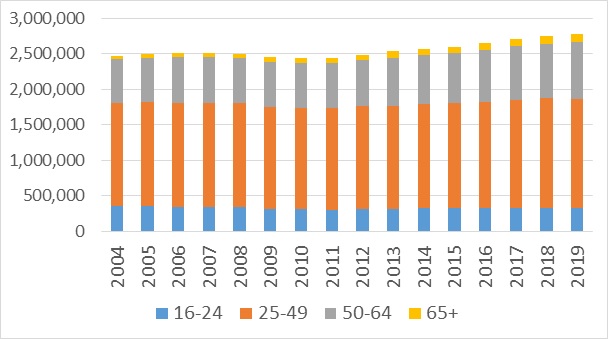

In recent years the number of older workers has risen to historically high levels, as shown in the chart below showing Annual Population Survey data on the broad age profile of people in employment in the West Midlands region.

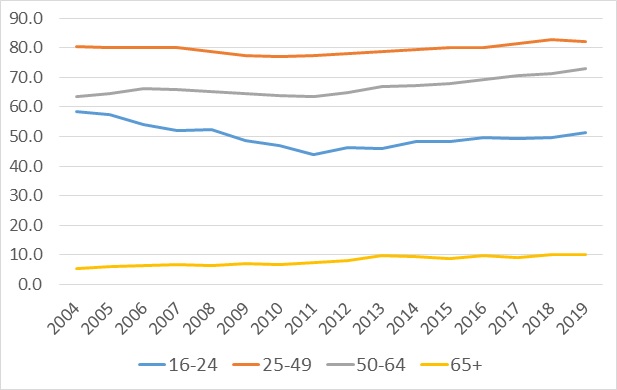

Whereas the employment rate for 16-24 year olds in the West Midlands region at 51.4% in 2019 remains lower than rates before the Great Recession, the chart below using Annual Population Survey data shows a steady increase of nearly 10 percentage points in the employment rate of 50-64 year olds since the Great Recession. The employment rate for those aged 65 years and over has also risen substantially, albeit employment rates for younger and older workers remain lower than for those aged 25-49 years. However, national analysis shows that people aged over 55 years represented more than half of the employment growth in the decade to 2018.

National analysis shows that people aged over 55 years represented more than half of the employment growth in the decade to 2018. People aged 50 years and over accounted for three-quarters of the increase in employment over the period from 2004 to 2019. The statistics presented above show that this is a function of both population ageing (i.e. compositional change) and an increase in employment rates in the older age groups (i.e. behavioural change).

Do older workers merit special attention in the Covid-19 crisis?

All age groups face labour market challenges in the face of the Covid-19 crisis, with increases in the number of benefit claims and risks of further redundancies. However, older workers face a number of issues that they may merit special attention.

First, a recent report by the Learning and Work Institute for the Centre for Ageing Better highlights that older workers becoming unemployed face a greater than average risk of long-term unemployment. They are twice as likely to be out of work for 12 months or more as younger workers and almost 50% more likely as workers aged 25 to 49 years.

Second, older workers are less likely to return to work following redundancy than younger workers. Around one in three people (35%) aged 50+ returned to work after losing their job, compared to half (54%) of 35 to 49-year olds, and two out of three of 25 to 34 year olds (63%).

Third, statistics on adult learning in the UK show that older people are less likely than young people to participate in training. Nesta analysis highlights that 39% of those aged 55-64 years participate in adult learning compared with just over 60% of those aged 25-34 years. This means that older people may face particular challenges of upskilling if they need to change sectors/ take on new job roles.

Fourth, Nesta suggests that the fact that (in aggregate) older workers are less digitally aware and confident than younger workers makes it more difficult for them to transition to remote working (where that is a possibility). This is particularly the case for those in lower socio-economic groups where the use of the internet is lowest.

Fifth, there is evidence that older people perceive ageism/ employer stereotypes as a major barrier to employment. Recent evidence suggests that the greater health risk of Covid-19 for older people is thought to further exacerbate negative stereotypes.

Sixth, the developments above coupled with rises in the state pension ages place financial pressures on some older people, perhaps leading to pensioner poverty. The Covid-19 crisis means that these challenges are difficult to address through longer working lives. Rather increased numbers of older people may be forced into early retirement and/or have to forego a gradual retirement.

Conclusions and policy implications

While older workers have not been furloughed to the same extent as younger workers and have not been the focus of policy to the same degree, once they are out of work they tend to face particular challenges in transitioning back into employment. The evidence suggests that while a focus on young people is appropriate – especially so in the West Midlands metropolitan area given its younger than average population – this should not be at the expense of taking account of addressing the long-term unemployment, access to training to facilitate job changing and digital skills challenges faced by some older workers negatively impacted by the Covid-19 crisis.

This blog was written by Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.