Professor Anne Green investigates social mobility, both within classes and geographically reviewing how factors such as education, housing, internal migration, and socio-economic and cultural backgrounds makes a difference to people’s opportunities.

Introduction

On 23rd July the Social Mobility Commission published an important report entitled ‘Moving Out to Move On’ investigating the link between internal migration in Britain, disadvantage and social mobility. These are important issues analysts in the light of the Covid-19 crisis. The links between location and the geography of opportunity structures have long been of interest to geographers and local economic development analysts. The quantity and quality of jobs available locally are of particular importance for those with poor skills because they have fewer opportunities and face more constraints in the labour market.

There are also longstanding concerns about a mismatch between individuals’ perceptions of jobs that are physically accessible to them and those that are within reach. In the early 1980s, Derek Quinn from the Transportation and Engineering Department at West Midlands County Council investigated unemployed school-leavers’ familiarity with locations within Birmingham and decisions made in the process of job search. His analysis showed that there were accessible parts of the city where there were vacancies, but groups of school leavers neither considered nor applied for them. He cited a lack of cross-city bus routes and constraining knowledge beyond the city centre as an influencing factor. Later research investigating place attachment, social networks and mobility, used ‘mental maps’ to gain insights into young people’s knowledge of their local area also highlighted how perceived opportunities are a subset of objective opportunities and how place attachment influences aspirations. These analyses underscore how limited spatial horizons can limit social mobility.

So does geographical mobility have a positive association with social mobility?

Geographical mobility and accelerated social mobility: the ‘escalator region’ concept

In the early 1990s, Tony Fielding coined the term ‘escalator region’ to describe how London and the South East acted as an ‘upward social class escalator’ in the British urban and regional system. Using data for the 1970s, he outlined how it attracts to itself, through inter-regional migration, a more than proportional share of the potentially upwardly mobile young adults – these are the people ‘stepping on’ the escalator. Then he illustrated how they ‘rode up’ the escalator, in that London and the South East promoted these young people, along with its own young adults, at rates higher than elsewhere in the country.

Subsequently Tony Champion and Ian Gordon have extended the analyses for three subsequent decennial periods: 1981-1991, 1991-2001 and 2001-2011. Their results showed that London and the Greater South East continued to perform in the way originally conceived by Tony Fielding. It continued to receive a large influx of younger working-age people who exhibited stronger upward social mobility than longer-term residents, who in turn had higher progression rates than those elsewhere. As such, they confirmed that it could be seen as a ‘deep structural’ process.

But in the period from 2001 to 2011 they found that it did not operate as strongly as in the 1990s either in terms of the career progression gained by its in-migrants or the extent of its advantage over the next largest cities (including Birmingham). There are several possible explanations for the slowdown in the first decade of the 21st century. The first is an increase in immigration to London and the South East resulting in fewer opportunities for internal migrants from the rest of the country. A second is an increase in the number of graduates to take up job opportunities. A third explanation is an improvement in opportunities for career advancement in second-tier cities, which bodes well for graduate attraction and retention. However, these analyses only go up to 2011.

So what does the picture look like incorporating more recent evidence on geographical mobility – and its relationship with social mobility?

Research by Michael Thomas on the motives for internal migration in Britain using geo-coded microdata highlights that the propensity to undertake employment- and education-related migration is highest amongst the young and highly educated. This fits with expectations from human capital models of migration. Traditionally longer distance moves have been associated with employment-related migration. Although employment and education-related motives account for a greater share of longer distance than shorter distance moves, they account for a minority of total migration events over 40 kilometres and family motives are equally important. This emphasises how a mix of factors influence migration decisions.

The ‘Moving Out to Move On’ report published in July 2020 is distinctive in its concentration on deprived areas and moves from and to them. In the report, ‘movers’ are defined as those living as adults in a different area to the one where they grew up. These ‘movers’ are contrasted with ‘stayers’ who remained in the area where they grew up. The focus of the statistical analysis element of the mixed methods study (which also incorporates interviews, focus groups and roundtable discussions with stakeholders) is on whether movers have better employment outcomes compared with people who did not migrate and whether migration from deprived areas is higher or lower than migration from more advantaged ones.

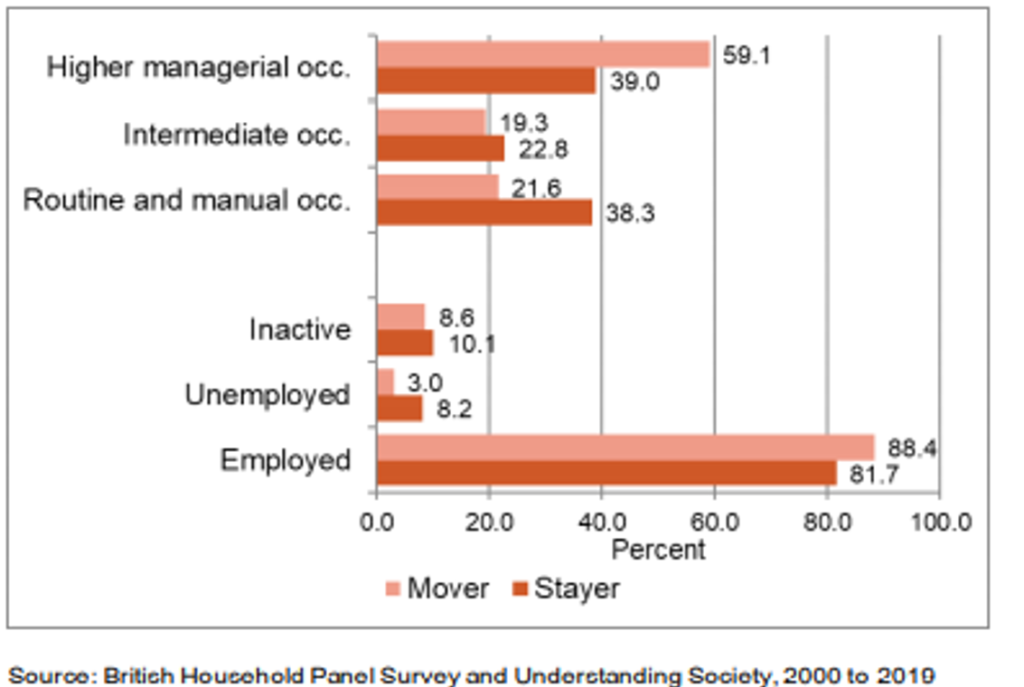

Key findings confirm that the early 20s is the peak age for moves. In this age group moves to study and to find work dominate. Movers are more likely to have higher educational levels: 56% of movers have a degree compared with 36% of stayers. Movers are more likely to be employed and less likely to be unemployed. They are also more likely to be in higher managerial occupations and less likely to be in routine and manual occupations (as shown in the chart below which depicts employment outcomes by migrant status).

In accordance with the concept of the escalator region, movers outperform stayers when taking account of socio-economic background: 47% of movers from a routine and manual socio-economic background work in higher managerial or professional occupations, compared with 30% of stayers from a similar background. Yet economic gains moving are greatest for those from most deprived areas.

In general, better off people move to better-off areas, while poorer people move to poorer areas. This compounds social and geographical differentials.

Housing affordability is a key factor constraining stayers from moving. Yet stayers cite quality of life, personal connections and low living costs as benefits of staying.

A trend to lower geographical mobility?

Many factors drive geographical migration within countries. Anne Green identifies five main groups of drivers: (1) changing demography, (2) macro-economic and labour market factors, (3) technological developments, (4) societal and non-economic considerations and (5) other markets, regulatory and institutional structures. These drivers sometimes pull in the same direction and sometimes work against each other. Whereas some, such as ageing, unambiguously reduce migration, others, like technological change, simultaneously enable mobility and immobility. The increasing heterogeneity within demographic and economic sub-groups of the population, technology-enabled separation of economic activities across geographical areas alongside the extended reach and penetration of social networks suggest that understanding how drivers play out in practice is far from simple. Migration is not just an individual decision but involves trade-offs at the household level. Life events and housing considerations are also important.

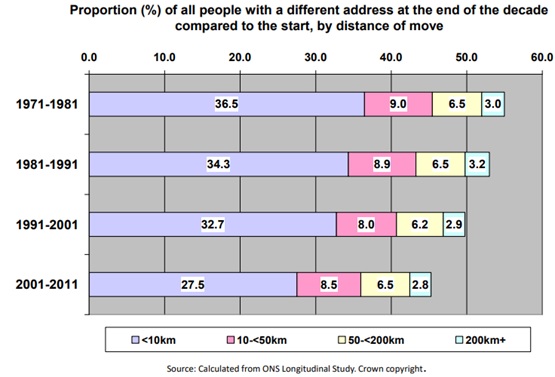

Analyses by Ian Shuttleworth, Tony Champion and colleagues point to a slowing of internal migration in England and Wales. As the chart below shows, the proportion of people changing at least once in a decennial period reduced from 55% in 1971-81 to 45% in 2001-2011. A decrease in short distance moves accounts for most of the reduction. Moves to and from higher education have helped maintain longer-distance moves, so highlighting the importance of moves involving higher education in understanding geographical mobility over longer distances.

International evidence also points to declining internal migration. This is most evident in the USA – where the rise in rootedness it is evident across all distance categories. It is evident in Canada and Australia – particularly at long distances. In Europe the picture is mixed, varying between countries.

A reduction in internal migration brings both positive and negative features. More stable communities and greater social capital are pluses. However, this may be at the expense of more closed attitudes; geographical mobility is associated with open attitudes. On the negative side of the balance sheet, a slowdown of geographical mobility may also mean less social mobility and entrenchment of spatial differences.

Policy suggestions

The ‘Moving Out to Move On’ highlighted four policy suggestions to help build better outcomes for people in deprived areas and improve local fortunes more generally.

First, it suggests the universities and colleges should work together to ensure local areas have a coherent and flexible offer for school leavers. Here it is important to recognise that routes into and from further/ higher education and into employment are less clear for those leaving school with fewer qualifications than for those who have performed well academically and where pathways are more established. Colleges and universities also have a role in helping to tackle social and financial barriers faced by those from less advantaged backgrounds who move to study. The Office for Students is active in funding knowledge exchange activities that facilitate engagement of students with local businesses/ organisations, with a particular focus on students from disadvantaged backgrounds to help ensure better outcomes.

Secondly, the report highlights that employers and local authorities should work together to identify and correct mismatches between local skills and local needs. Employers can extend and diversify their talent pool by recruiting both locally and further afield by facilitating flexible working – so that opportunity becomes less reliant on geography.

Thirdly, in order to facilitate geographical mobility and the connectivity of people to opportunities, it suggests that local leaders should prioritise digital infrastructure and skills, transport connections and good quality affordable housing. Such policies are important in enhancing place attractiveness.

Fourthly, the report highlights the importance of developing pride in place, including through local leaders working with community groups.

How will geographical and social mobility evolve going forward? Implications of the Covid-19 crisis

The evidence suggests internal migration is declining over the longer-term. Technology-enabled home working for some people – particularly the highly qualified who drive geographical mobility for education and employment – has shown more people that they can work from home, at least for some of the time. This might suggest that the Covid-19 crisis acts as a further driver for less employment-related internal migration in Britain, so accentuating current trends. Family and amenity factors might then play a more important role in driving migration decisions and the choice of where to live and shifting residential preferences are important here. Nevertheless, being able to travel to work say two-three days per week is likely to be important for some people. This means that place attractiveness – which comprises the economic, housing, cultural and environmental offer – becomes more important for local and regional economies, in terms of both retaining and attracting people.

Does less migration mean reduced social mobility – especially in the face of geographical inequalities in the quantity and quality of opportunities? Resource constraints given the competing pressures on spending posed by the Covid-19 crisis, at least in the short-term, may reduce prospects for targeted policies aimed at improving social mobility and the geographical distribution of opportunities over the short-term although the ‘levelling up’ agenda is important in this space. Evidence suggests that internal migration is already on the decline. Will the escalator that has operated to enhance social mobility of movers slow, stop or even go into reverse? Or will opportunity be less reliant on geography than in the past?

As outlined above, the escalator has become entrenched in the British urban and regional system. If in 2020, fewer young people move away from home areas to pursue educational opportunities at universities this has implications for geographical mobility – not just in the short-term but also in the longer-term, given that migration is not just a ‘one-off’ event but rather shapes future behaviours, and of their families, over the life course. So fewer undergraduates moving away in the first instance and more opting for local work has implications for the future too. In the short-term, it may mean a larger talent pool on which some local economies can draw. Conventionally graduate retention is interpreted as a ‘good thing’ for local and regional economies. But there can be advantages, both locally and nationally, of geographical mobility involving the young highly qualified getting on and riding the escalator in the early stages of their careers and then stepping off the escalator and bringing their skills and experience back to their areas where they originated once their careers are established. This suggests that local and regional economies need to make places attractive to people at all stages of the life course.

Brexit and immigration policy add to the complexity. Fewer international migrants competing for jobs – especially in London and the Greater South East – could open up the potential for more geographical mobility given that international migration has been cited as filling some of the opportunities that might have been taken previously by internal migrants.

Finally, voluntary job changing is positively associated with economic buoyancy. The economic downturn associated with the Covid-19 crisis could be expected to mean that those in employment are more reluctant to change jobs while for those seeking employment competition intensifies. It is hard to achieve social mobility in a depressed labour market.

Further Reading

Pelikh A, Borkowska M and Patel R (2020) Understanding Geographical Mobility: Data note, Understanding Society, ISER, University of Essex.

Purcell K, Elias P, Green A, Mizen P, Simms M, Whiteside N, Wilson D, Robertson A and Tzanakou C (2017) Present Tense, Future Imperfect? Young people’s pathways into work, University of Warwick.

White R J and Green A E (2011) ‘Opening up or Closing down Opportunities?: The Role of Social Networks and Attachment to Place in Informing Young Peoples’ Attitudes and Access to Training and Employment’, Urban Studies 48(1) 41–60.

This blog was written by Professor Anne Green, Professor of Regional Economic Development, City-REDI / WM REDI, University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI / WM REDI or the University of Birmingham