In celebration of International Women's Day, Alice Pugh looks at how employers can help women overcome the obstacles they face in the workplace. This blog is part of an International Women's Day series.

Research shows that women start their careers with as much ambition as men on average (Abouzahr et.al,2017), and in an international survey by The New York Women’s Foundation, 59% of women stated that ambition was essential to a successful career. Therefore, why are there significantly fewer women in senior leadership roles compared to men?

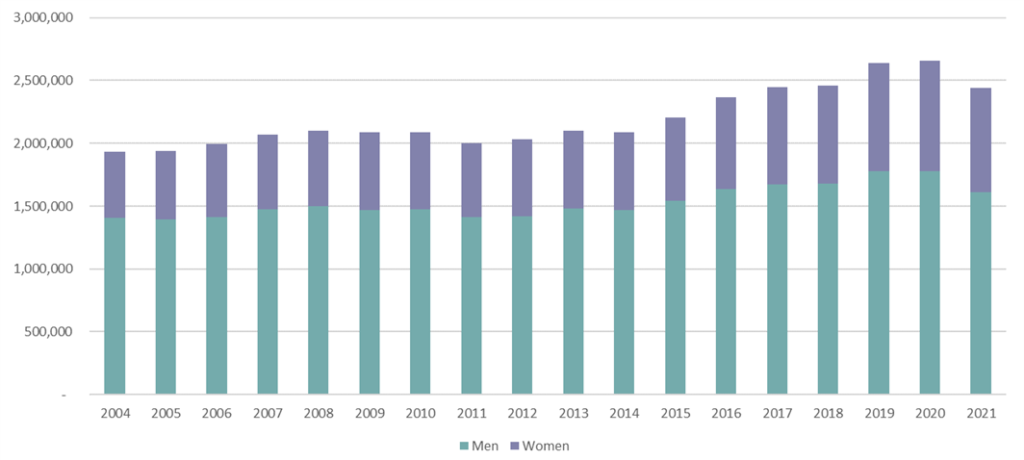

Figure 1 below shows the number of corporate managers and directors in the UK by gender, the graph clearly demonstrates that there are far more men in the most senior positions compared to women.

As of 2021, 66% of corporate managers and directors were male, with 34% female. The question this blog aims to answer is – why women are hitting a glass ceiling and unable to reach the same career level as men?

The Motherhood Penalty

Claims are often made that women are less ambitious than men when it comes to occupational gain because they have greater ambitions to be mothers. However, research has shown that mothers when surveyed were as equally ambitious as women without children (Abouzahr et.al,2017).

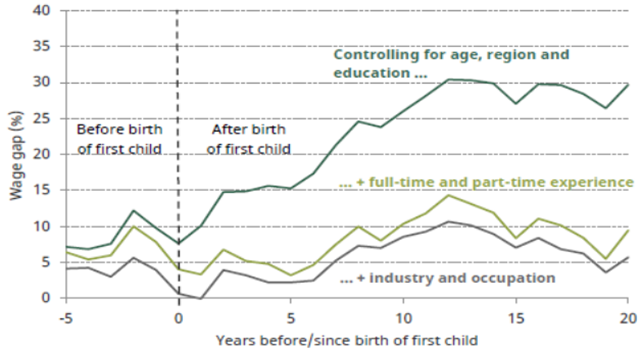

Nevertheless, even though mothers are as ambitious as women without children, having a child can have a significant impact on women’s wages and career progression. Figure 2 below is based on research by Costa Dias et.al (2018), which demonstrates the impact that having a child can have on a women’s career progression in the UK. The figure models the gender difference in wage progression following the birth of the first child. The research found that before the birth of a first child, there is a pay gap between men and women but following the birth of a first child this gap rapidly grows, generally increasing over time.

Figure 2: Gender wage gap by time to/since the birth of a first child, controlling for association between wages and other characteristics

However, rather than being a mother, the divergence was largely due to a symptom of becoming a mother, which is childcare. Many new families cannot necessarily afford to pay for full-time childcare; therefore, one parent usually must go part-time to care for their child or children. According to research from Pregnant then Screwed and Mumsnet (2022), in a survey of more than 26,000 parents of young children in the UK, 62% said that their childcare costs the same or more than their monthly rent/mortgage. With 43% of mothers stating that they have considered leaving their job due to the costs and 40% saying they have to work fewer hours than they would prefer as a result of childcare costs. This is no surprise given the UK has some of the highest childcare costs in the developed world, with net childcare costs for a couple on the average wage, accounting for 22% of the household income.

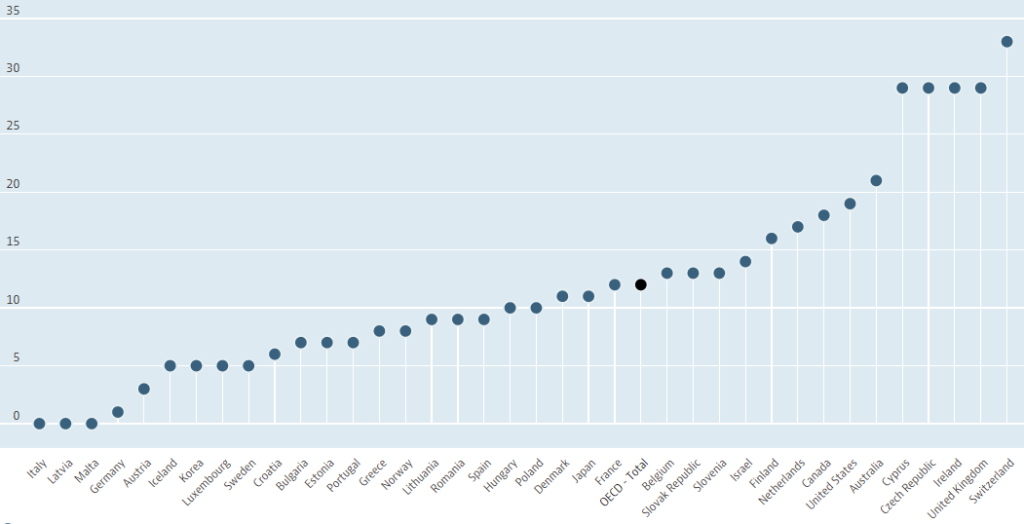

As can be seen in figure 3 below, this is the second highest cost out of the OECD countries, with only Switzerland having a higher cost for households, the OECD average is 9% of household income.

Figure 3: Net Childcare costs as a percentage of household income, for a couple on the average wage

Societally the role of childcare provider falls to the mother, once women start part-time work to care for their child this shuts down wage and career progression (Costa Dias et.al, 2018 and Bukodi et.al 2012). Whilst the average full-time employee sees year-on-year wage growth, as a result of increased experience, part-time workers experience virtually no growth once they begin part-time work. The research found that the gender difference in rates of part-time and full-time work accounts for half of the widening of the gender wage gap in the first 20 years of a family’s first child’s life (Costa Dias et.al, 2018).

Attack of the Clones

Studies by Atkinson, 2011; White et.al, 2012; Bagilhole, 2016; Shepard, 2017; and Kumra, 2010, all identify that there was a tendency for social cloning in the promotion process. Whereby, those in positions of authority tended to seek to champion and promote individuals who were similar to themselves. The similarities could take many forms, including career path development and leadership style. Given that many senior positions are often male-dominated, it places women at a disadvantage, as they are less likely to be seen as possessing the relevant qualifications of the archetypal candidate. Research has also found the process of social cloning strengthens where informal systems for hiring and promotion are conducted through networks (Leung et.al, 2015).

The Old Boy’s Club

Several different studies have found that male employees are more likely to spend time socialising with male employers or managers, comparative to female employees. The result of these informal networks is that male employees can engage in self-promotion when in social or networking settings more than women, especially as men are more likely to make up managerial positions the higher they progress. This can then lead to greater opportunities to receive more high-profile projects than the female counterparts, leading to increased development of career capital and thus a greater likelihood of promotion opportunities. These networks also allow for greater sharing of opportunities and promotion of successful work. Additionally, women are usually excluded from these socialising opportunities as a result of childcare responsibilities, which can limit their ability to actively engage in these informal networks (Jones, 2019).

The Equality and Human Rights Commission found in the UK that a third (32%) of the FTSE 350 companies still rely heavily on personal networks of current and recent board members to identify potential candidates, with the majority of these companies not even advertising new posts and simply looking through their networks. Finding that women have less access to these networks than men especially as women are less likely to be promoted to senior positions in the first place to engage in such closed networks.

Solutions to help women progress

Flexible working

Offering the opportunity for greater flexible and agile working environment, especially in senior positions, could help women’s work progression. Especially, as it may lessen the time spent working part-time which appears to be the largest detriment to a woman’s career progression (Jones, 2019). Additionally, the implementation of flexible working may allow for a more equal distribution of childcare responsibilities between couples, as it would also enable men to take on more childcare responsibilities than they have in the past (CMI and GEO, 2019). Potentially it could also help retain and attract female employees and reduced economic inactivity amongst this group (ibid).

Childcare Sector Investment

The Centre for Progressive Policy (Franklin and Hochlaf, 2021) found that if women had access to adequate childcare services, and were able to work the hours they wished, it would increase their earnings by £7.6bn to £10.6bn per annum- potentially generating up to £28.2bn in economic output per annum. They recommended that the government should provide greater funding for subsidised childcare, especially in a child’s early years and during school holiday periods. Such investment would enable parents to afford childcare, whilst ensuring that there is capacity in the sector, improving both parents’ abilities to commit to a greater number of working hours.

Clear hiring policies

Women often miss out on progression opportunities because processes around hiring and progression are often quite opaque and informal, in many cases with job opportunities and sponsorships happening without women having access to the mechanisms of how they work (Jones, 2019). Often the old boys club and self-cloning of managers can play a part in the offering of promotions and notification of career opportunities. A clear, transparent, and formal hiring process can reduce the risk of these barriers. However, as found by Jones (2019) this has to be supported by accountability mechanisms, otherwise, these processes can be seen as symbolically meritocratic procedures and actually have a negative impact.

This blog was written by Alice Pugh, Policy and Data Analyst for City REDI and WM REDI.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.