This blog post has been produced to provide insight into the findings of the Birmingham Economic Review.

The Birmingham Economic Review 2018 is produced by City-REDI, University of Birmingham and the Greater Birmingham Chambers of Commerce, with contributions from the West Midlands Growth Company. It is an in-depth exploration of the economy of England’s second city and is a high-quality resource for organisations seeking to understand Birmingham to inform research, policy or investment decisions.

This post is featured in the full report and report summary here.

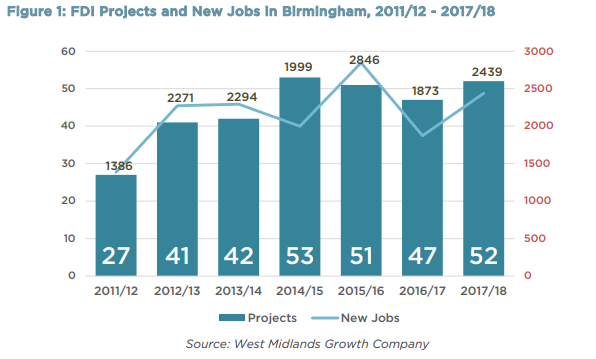

The Birmingham City region continues to do the best for inward investment outside London. This offers an interesting commentary on the contribution that inward investment makes to productivity locally. If one takes as a benchmark that foreign firms have on average 15-20% higher productivity than local firms, and that a high proportion of inward investment for the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) region is in sectors with above average productivity, then this indicates the importance that attracting and retaining inward investment has for the local economy. Such sectors are also above average in terms of innovation, capital intensity and spending on R&D.

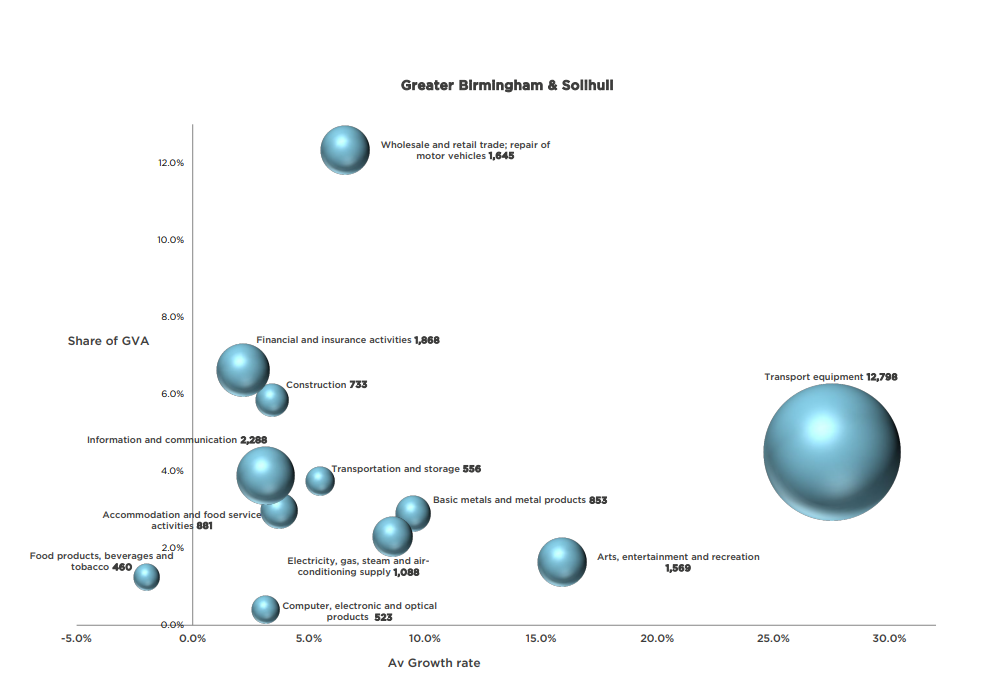

The figure below highlights the growth in employment of the sector, against the share of Gross Value Added (GVA) of the sector, for the main Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) sectors. This indicates the relative importance of the sector to the West Midlands economy, as well as giving an indication of relative performance. Clearly, this highlights the importance of the transport sector, but it also, for example, illustrates that inward investment in food and drink contribute less to productivity – though of course these sectors provide employment for less skilled workers. Indeed this illustrates neatly a finding from the academic literature, which is that with only a few exceptions, inward investment contributes to productivity, OR it generates significant employment opportunities. It is clear that the transport sector does both, and to an extent so do financial services, but most other sectors fall into one category or the other.

What is therefore required at a local level in terms of an inward investment strategy is a mix of these sectors. The high value-added investment brings new technology, potentially spillovers, and develops knowledge transfer and training into supply chains and related sectors. However, in order for this to work effectively, there needs to be an emphasis on developing both delivery capacity and absorptive capacity in these related sectors.

What is therefore required at a local level in terms of an inward investment strategy is a mix of these sectors. The high value-added investment brings new technology, potentially spillovers, and develops knowledge transfer and training into supply chains and related sectors. However, in order for this to work effectively, there needs to be an emphasis on developing both delivery capacity and absorptive capacity in these related sectors.

- Develop an inward investment strategy through greater understanding of why firms seek to invest in the region.

High value-added FDI adds significantly to the underlying technological base of the economy but creates fewer jobs, while FDI that generates large scale employment is typically (though not always) associated with less cutting edge technology. So our strategy needs to communicate which sectors will be able to attract inward investment of what type, and where this most likely to be sourced. This emphasises not ‘sectors’ as such, but value chains, where activity within the region is positioned within an international setting, and the vulnerabilities of value chains to global changes, or to macroeconomic factors such as exchange rate changes or changing terms of trade.

- Focus inward investment efforts on sectors where free trade with the EU is less important.

This means seeking to maximise the benefits of large scale investments in infrastructure (in the context of the Midlands, HS2); recognising the need, for example, to support skills in jobs around project management and professional services associated with infrastructure projects; and building robust supply chains to support infrastructure development.

- Maximise the returns on inward investment.

This again requires an understanding of the benefits of inward investment, for example of the benefits to supply chains or through knowledge transfer from inward investors into local firms. In order to understand how policy levers in this space can be applied, one has to understand the motivation and financing of FDI. For example, in the years prior to the financial crisis, a high proportion of global FDI was funded by debt, that has since not been available. One response, therefore, needs to seek FDI which is genuinely exogenous to the UK, that is, it is funded, not by loans financing raised from UK capital markets, but from the home country. This varies by country. Much Asian FDI, for example, is now funded by cash flow generated in the home country, compared with US, EU and Japanese investment which is typically debt financed. A country strategy is required therefore for investment promotion agencies as well as a sectoral strategy.

- When selecting key sectors for inward investment, focus on job creation as well as value added.

The WM Growth Company, previously Marketing Birmingham have been very successful in attracting inward investment into the region. It should be recognised that they have a wider remit than simply generating productivity growth, in that they have to undertake a matching exercise between the regions value proposition, and the type of investment that they can attract. It should be recognised that, given the nature of the skill distribution across the region, that from an employment and productivity position, all investment is good investment. While obviously high skill, high value-added jobs will increase productivity the most, generating employment for less skilled people may well increase aggregate value added by more. Equally, lower value-added jobs tend to fill from the local labour market, rather than attracting people in from outside.

- Focus on job quality rather than just the number of jobs created

In terms of the wider remits of WMCA and of this commission, it is also clear that social inclusion and skill development are important drivers of productivity. In terms of the contribution that the region’s inward investment strategy can make to this, the nature of jobs created is also important. The skills analysis conducted as part of this commission rightly focuses on the supply side in terms of skill creation, but it is important to recognise the role that inward investment can play in the demand for skills. It should be recognised here that often inward investment, and their accompany supply chains have a disproportional influence with policymakers, as the current Brexit debates are illustrating. Often inward investors can influence skills strategies in terms of filling skills gaps in ways that local firms often find challenging. Regions can then use the needs to service inward investors as part of their ask of government around (devolution of) education and training.

This blog was written by Professor Nigel Driffield, Warwick Business School, The University of Warwick.

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.