Professor Matthias Kiese discusses the structural transformation of the Ruhr in Germany, a region attempting to leave behind its industrial past and move towards a knowledge-based economy.

A broader analysis looking at the progress the Ruhr region has made towards levelling up over the last five decades can be found in the Industrial Strategy Council’s report co-written with City-REDI researcher Dr Abigail Taylor “What does it take to “level up” places?“.

The structural transformation of the Ruhr

With its 5.1 million inhabitants, the Ruhr is Germany’s largest urban agglomeration. A polycentric region of 53 cities, of which all but the largest eleven are grouped into four counties, its growth was driven by coal mining and the steel industry since the 19th century. After decades of structural transformation, has the Ruhr managed to shake off its rust and to catch up with the general trend towards more knowledge-based economic activities?

The Ruhr has made considerable progress but more remains to be done: the region has developed a dense network of large universities, which have supported the growth of the knowledge economy. However, this has yet to become fully-fledged, and there are signs of rising disparities.

After six decades of crises and heavily subsidised structural transformation, the last coal mines in the Ruhr closed in 2018. This is backed up by improved air quality, reclaimed brownfield land, industrial heritage sites that helped the region attract 4.4 million tourists in 2019, as well as the establishment of large universities since the 1960s, which now boast sizeable student populations. Mission completed? Has the Ruhr joined the track of modern metropolitan economies increasingly based on the generation and application of knowledge for employment and income?

Growth of the University Sector

The Ruhr’s dense university landscape is still relatively young and was initiated with the opening of the Ruhr University in Bochum in 1965. Further universities followed in Dortmund (1968), as well as in Duisburg and Essen in 1972. Following the establishment of universities of applied sciences, the region is now home to 22 universities spread across 38 locations. While the older and larger universities are all located in the southern part of the Ruhr, the economically disadvantaged North of the region with its weaker social structure saw only the foundation of smaller universities of applied sciences over the past two decades.

In 2018, the region’s universities employed 3,019 professors and a total academic staff of 13,742, catering for 256,630 students – or 188,670 if you deduct the distance learning university of Hagen. Between 2007 and 2016 alone, the Ruhr’s student population increased by 80 per cent, while staff numbers only grew by 47 per cent, contributing to one of the most unfavourable student-professor ratios among all metropolitan regions in Germany. Correspondingly, competitive third party funding as a measure of research excellence also lags behind. Nationwide, the three large universities of Bochum, Duisburg-Essen and Dortmund rank seventh, eighth and 16th by student numbers, but only 22nd, 31st and 37th by funding from the German Research Foundation in 2014-2016.

The knowledge economy

Given these capabilities for knowledge production and dissemination, how about the Ruhr’s knowledge economy? The Ruhr as a whole lags behind the averages of Germany and the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) in spending on and employees in research and development (R&D) – common measures of inputs in the innovation process. A similar gap is evident in patent applications as a measure of new technical knowledge not yet exploited in the marketplace. This is closely linked to the underrepresentation of knowledge-intensive manufacturing industries, as these are defined by their R&D intensity. While the proportion of employees in high-tech industries fell from 10.5 per cent to 10.2 per cent nationwide between 2009 and 2015, only Dortmund was able to increase its share from 6.0 per cent to 6.5 per cent, while the three other large cities Bochum, Duisburg and Essen fell behind even further during that period. In part, this gap reflects the overall low share of manufacturing still left in the Ruhr.

In contrast to manufacturing, knowledge-intensive services show a greater tendency to concentrate in urban agglomerations. Although the Ruhr has a slightly above-average proportion of employees in this sector, which increased from 19.8 per cent to 20.3 per cent between 2010 and 2015, it still lags more than four percentage points behind the seven major German metropolitan regions. Creative and cultural industries are another prominent segment of modern urban knowledge economies. The fact that their employment shares in Bochum, Dortmund and Essen are roughly in line with the national average is therefore not satisfactory, as the average includes many non-metropolitan regions and cities like Munich, Cologne or Düsseldorf boast significantly higher shares.

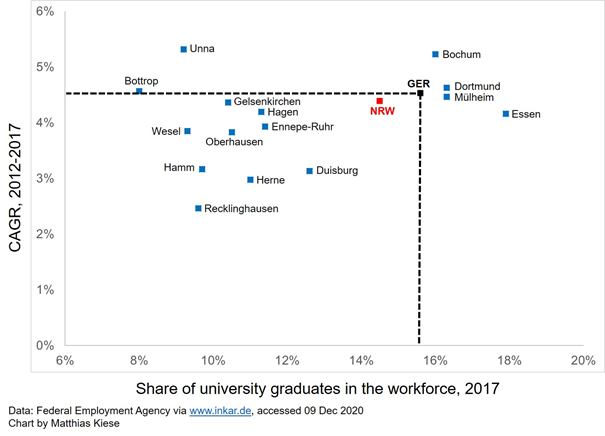

A key indicator of the knowledge economy is the share of university graduates in the workforce. Data over a longer time period is not currently available but would likely show a considerable increase in graduate numbers over time. As the chart below shows, the current share of university graduates in the workforce is marginally above the national average in the cities with the largest universities in the Ruhr, i.e. Bochum, Dortmund and Essen. However, their shares are a far cry from the ratios reached by university towns such as Erlangen, Munich, Jena, Darmstadt and Stuttgart. Attracting mobile graduates from other places, these hotspots of the German knowledge economy all score above 30 per cent.

Furthermore, the majority of cities and counties in the Ruhr clearly lag behind the national average, dragging the NRW average down. While universities have contributed to the region’s transformation through their ample supply of graduates, the Ruhr’s knowledge economy is not yet able to absorb all of them, leading to the outflow of graduates to other parts of the country. The picture is clear: The Ruhr’s still feeble knowledge economy cannot absorb the large number of graduates produced by the region’s vast university landscape, leading to the outflow of graduates to other parts of the country – and some of this brain drain is directed to the innovation hotspots in the South.

Another important message is the widening gap between the large university cities, which are modestly catching up, and the large tail of laggards falling further behind. While Germany as a whole shows regional convergence for this indicator in the 2012-2017 period, cities and counties diverge slightly in the Ruhr, as there is a positive but weak correlation between the 2012 share and the subsequent growth rate.

Clusters and spin-offs

Universities are already working as engines of emerging clusters through spin-offs and the attraction of firms seeking to tap the vast talent pool, especially in information technology. Many of these cluster around the campus of the Technical University of Dortmund with its incubator and technology park, which are among the oldest and largest in the country. Neighbouring Bochum is following in these footsteps with the ongoing transformation of a former Opel car plant site into a hub for research centres and knowledge-based firms. It is important that these developments around the large universities inspire the rest of the Ruhr, if the knowledge infrastructure is to be strengthened more broadly, and if spillovers from the leading cities are to be stimulated. More fundamentally, however, universities as engines of the Ruhr’s emerging knowledge economy need more fuel in terms of funding and academic staff. Channels of knowledge transfer need further strengthening, too – especially nurturing a culture of entrepreneurship takes time and persistent effort in a region once dominated by large companies.

This blog was written by Matthias Kiese, Professor with the Institute of Geography, Ruhr University Bochum.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.