Welcome to REDI-Updates. REDI-Updates aims to get behind the data and translate it into understandable terms. In this edition, WMREDI staff look at the government's flagship policy - Levelling Up. We look at the challenge of implementing, understanding and measuring levelling up. In this article, Alice Pugh examines policy and funding changes brought in by the Levelling Up White Paper, and what further actions the government needs to take to Level Up. View REDI-Updates.

The UK – a politically and fiscally centralised economy

The UK has some of the worst inter- and intra-regional economic and social disparities of any advanced nation in the world. Historically, the UK has also been one of the most politically and fiscally centralised economies in the developed world. The centralised nature of government decision-making has insufficiently weighed spatial considerations within the design and delivery of policy initiatives. Often it has been a significant contributor to the UK’s widening disparities.

A significant proportion of discretionary government spending, especially investment spending, has often been geographically skewed. For instance, R&D and transport funding and spending have often been concentrated within the South East and London, often due to the application of the benefit-cost ratio which can lead to investment in the places which have the greatest return on public investment. However, ensuring that public spending reaches places where it is most needed is difficult. The best source of data on subnational funding/spending on a regular and consistent basis is usually the ONS Country and Regional Analysis, but is partial and insufficiently granular. Due to this the spatial pattern of government spending/funding is often unclear and can mean the government policy is sometimes acting in a ‘place-blind’ manner.

The effective targeting of investment

Therefore, in the Levelling Up White Paper (LUWP) the government has stated that to support more effective targeting of investment central government will require the analysis of spatial breakdown of spending and benefits from the outset of programmes (this is also a requirement set out in the revised Green Book 2020). Initially, this was trialled during the Spending Review 2021 (SR21) and learning from this, the LUWP has stated that the ‘government will improve its use of spatial impact programmes’ to better inform decision making. Additionally, a significant proportion of current direct public funding is determined by formulae, such as the National Funding Formula. In order to improve the formula-based funding/spending, the government will review current formulas used to be more considerate of spatial economic and social disparities, to ensure it is targeted toward those most in need.

Furthermore, over the last decade, cross-departmental coordination of place-based policies is still relatively rare. With local authorities and institutions often left to link programmes, policies and funding themselves, with multiple competitive local growth funding pots, emerging over the last decade. This has led to a patchwork of fragmented funds, separate but often overlapping, each seeking to improve local place-based economic development.

Local government has pointed to the inefficiencies of this system, including complexity in decision-making and reporting burdens, which result from the number of local funding pots. Many local authorities have limited capacity and expertise to navigate multiple funding pots, develop investable projects and achieve the right mix of capital and revenue to target long-term priorities.

Streamlining the funding landscape

In order to deliver a more ‘transparent, simple and accountable approach’, the UK government aims to “set out a plan for streamlining the funding landscape this year” including a commitment to help local stakeholders navigate funding opportunities. This will include the reduction of unnecessary proliferation of individual funding pots, supporting greater alignment between revenue and capital resources and ensuring robust monitoring and evaluation to understand the impact of investments. However, the government did not set out in detail how it intends to streamline and simplify funding but will outline this later within the year.

The simplification of these funding mechanisms has been welcomed by institutions and analysts. The DHLC will improve evaluation and monitoring following a report by the National Audit Office. Which found that a failure to implement evaluation and monitoring on previous projects and programmes, left the department unable to assess what had worked in best practice. It is positive, therefore, to see that greater evaluation and monitoring will be taking place when funding initiatives for local growth.

New spending and funding

After review it appears that two major investments within the entire LUWP were announced for the first time within the LUWP, these being the three £100m Innovation Accelerators and a £1.5bn Levelling Up Home Building Fund; the latter will be provided through loans and funding was first announced in 2020. The majority of other funding was difficult to track. For instance, the document highlights Multiply and the Youth Investment fund as part of its commitment to levelling up, however, funding for both was already announced in the SR21 and will be funded through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF). Furthermore, a significant proportion of the funding/ spending linked to the LUWP was already announced in either 2020 or 2021 to combat the impact of the pandemic, such as the Community Ownership Fund and the Culture Recovery Fund.

The majority of funding/spending cited within the LUWP appears to be not new money. Most have already been announced as part of other programmes or in previous spending reviews. It is unsurprising that there is little to no new additional funding in the LUWP, given the toll that the pandemic took on government finances; with the Chancellor being strident on funding, as all spending for the next three years has already been allocated through last October’s spending review. Instead, the LUWP is more of a review into how funding already announced, separate from levelling up funds, has or will contribute to levelling up. However, the main aim of the majority of these funds was never levelling up, therefore their effectiveness in achieving some of the missions in the LUWP may be limited.

The Centre for Inequality and Levelling Up (CEILUP), found that of the funding or spending linked to the LUWP, little of it was new funding to achieve the stated missions and over half of the money was dedicated to transport infrastructure only. CEILUP assessed that it will be a significant task to ensure that this spend relates to the specific levelling up missions and supports communities experiencing the greatest social and economic challenges. The Centre for Cities and Centre for Progressive Policy both highlighted that the majority of funding linked to the LUWP is short or medium term and this may mean that the Treasury is not behind the agenda in the long run. The social and economic disparities have been deeply entrenched over decades in the UK and addressing these complexities will take long-term commitments and the appropriate long-term funding to support them.

Furthermore, whilst there will be increased powers to devolved nations and local institutions, there has been no additional funding provided to them to increase capacity. Already, many of these local institutes are struggling, due to drastically reduced budgets under austerity. Providing them with additional responsibility whilst failing to provide additional funding, will stretch local budgets even further.

Where is the funding being spent?

Currently, £1.7bn of the Levelling Up Fund (LUF) has been announced, with the majority of these projects being capital infrastructure projects. The Centre for Levelling Up (CELUP) found that 73 bids were awarded to Local Authorities (LAs) in England and of these 66% of projects were awarded to LAs in the 30% most deprived areas in England. However, analysts did find that less than half of the government’s own priority areas received any funding in the first round. It should be noted, however, that London and the South East, usually high priority for funding, only received 10% of funding in the first round. Whilst it is welcome that the majority of funding was spent outside of the South East and London, the government needs to ensure that the priority areas are being targeted effectively in the future.

Other than the LUF, the government states in the LUWP that the Towns Fund is also ‘complementary’ to the LUF and is available to local leaders to support levelling up initiatives in their area. However, a large proportion of the Towns Fund has already been allocated (£2.3bn out of £3.6bn), to local areas that were selected. However, there have been deep concerns surrounding bias and a lack of transparency in the selection process for towns invited to participate in the Fund. The House of Commons Public Accounts Committee found that the rationale for selecting some areas and not others was unconvincing. Additionally, the justifications by ministers for selecting individual towns were vague and based on sweeping assumptions. For instance, 12 areas that were selected were ranked as a low priority by the government, the Institute for Government found all of these were in Conservative-held seats. The Committee also found that the government had not been open about the process it followed and did not disclose the reasoning for inclusion and exclusion. The lack of transparency fuelled accusations of political bias and risked the aims of the fund being undermined.

Future Funding

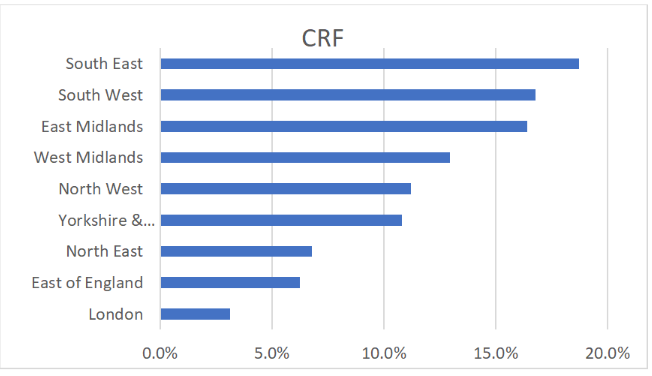

With regards to future ‘complementary’ or direct spending and funding, such as the UKSPF and the LUF, the government will need to be more transparent with devolved and local governments than it has been historically. However, last year the government did consult these bodies on a much greater level, with regard to the Community Renewal Fund (CRF). Within England, the majority of CRF funding was still skewed towards the South East (see Figure 1).

Additionally, the CELUP found that only 24% of CRF funding went to areas in the bottom 30% of indices of multiple deprivation rankings. This would indicate that the projects funded under CRF were largely weighted in favour of areas less in need of levelling up. Therefore, where future funds are concerned greater consultation will be needed with local areas to ensure that funding is being spent where it is needed most.

Additionally, the Institute for Government states that the government needs to set out greater transparency with regards to criteria for the allocation of funds based on an assessment of relative need at the local, as well as regional, level. This is especially important following the controversy surrounding the Towns fund, controversy surrounding levelling up may undermine the mission if local authorities believe future funding to be biased.

Additionally, if funding streams (such as UKSPF) are set to contribute to levelling up then the government needs to ensure that the missions within the LUWP are included as part of the monitoring and evaluation of projects. Without this then it will be difficult to measure the impact of initiatives under these funds, in relation to levelling up goals. Whilst the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, has set out a number of missions by which to measure the success of projects, unfortunately, there is a lack of granular data to sufficiently track these missions. Therefore, the department needs to work closely with the ONS to further develop these.

This blog was written by Alice Pugh, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI, WMREDI or the University of Birmingham.