In this blog, Annum Rafique examines the UK’s solar PV procurement landscape, highlighting how strong SME participation and regional diversity have positioned the sector to support the Government’s 45-47 GW target outlined in the 2025 Solar Roadmap.

This blog is part of ongoing work with the Innovation Procurement Empowerment Centre (IPEC), which seeks to position procurement as a strategic lever for fostering innovation and accelerating the UK’s transition to net zero.

Introduction

The Clean Power 2030 Action Plan published in 2024, set out the ambitious target of achieving 45-47 GW of solar power by 2030. The recently published Solar Roadmap outlines the vision to expand national solar capacity from 18 GW to 45 GW by 2030, emphasising innovation, domestic manufacturing, and ethical sourcing. However, the transition to a net-zero economy requires more than just ambitious targets. It requires procurement strategies that enable market growth, foster competition, and create pathways for innovative solutions to thrive. The procurement of innovation is critical because well-designed contracts and frameworks not only secure immediate delivery but also stimulate investment in new technologies, domestic manufacturing, and skills development.

The UK’s solar photovoltaic (PV) sector has seen notable growth over the past decade, driven by environmental priorities and supportive government procurement strategies. Public procurement can act as a powerful tool for innovation by incentivising new technologies, supporting domestic supply chains, and encouraging long-term investment. Unlike other policy levers such as grants or subsidies, procurement-led innovation creates a guaranteed demand, reducing market uncertainty and accelerating the commercialisation of emerging solutions. This not only de-risks investment for suppliers but also empowers the SMEs to participate and scale up, fostering a more resilient and diverse supply chain.

This blog examines solar PV public procurement contracts to evaluate how real-world market activity already aligns with the Roadmap’s priorities. By analysing supplier trends, regional dynamics, SME participation, and contract characteristics, we highlight both strengths and gaps and make the case for a smarter, more inclusive procurement approach to scale the solar industry.

Solar PV Procurement Landscape

A total of 1,199 individual solar PV contracts were examined from 2015 to 2024, sourcing the data from Tussells Dashboard, focusing on procurement contracts in England. These contracts were issued under 1,103 distinct procurement notices, implying that some notices had more than one supplier.

These awards, collectively worth £1.4 billion[3], had an average value of £ 1,167,221 per contract. These contracts were distributed across 661 distinct suppliers (an average of 1.8 contracts per supplier). Almost 466 suppliers (70.5%) won a single contract, while a smaller cohort of 195 firms secured two or more, including 12 firms that won five or more contracts. This distribution underscores both the breadth of market participation and the emergence of a core group of experienced providers.

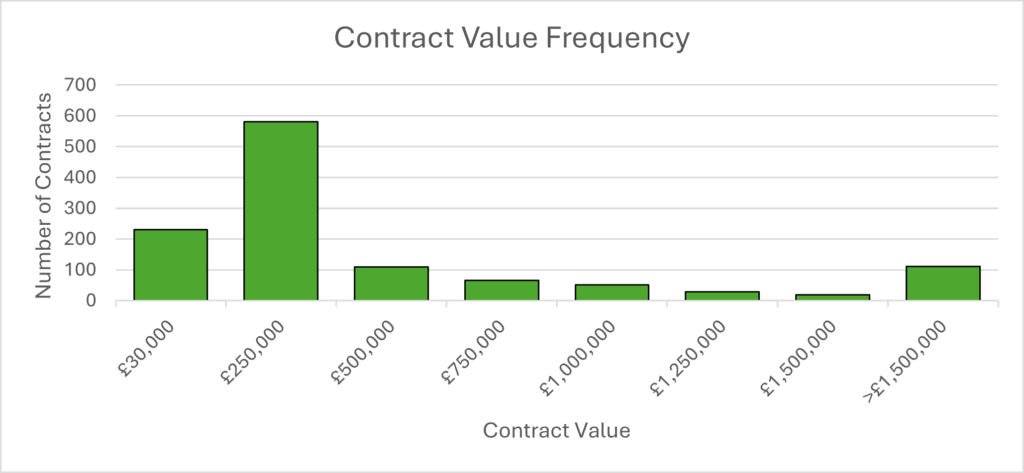

Contract sizes and durations offer further insight into buyer preferences and project scopes. Approximately 14% of all contracts were valued at under £30,000, and nearly 47% were valued at £250,000 or less, indicating that procurement is dominated by small to medium-sized projects, as shown in Figure 1.

The duration of these contracts is presented in Figure 2. In terms of duration, approximately 68% of contracts ran for 12 months or less, reflecting a strong focus on discrete, site‑specific installations rather than long‑term service or maintenance frameworks.

Figure 2: Duration of Contracts

Supplier Location

London leads in supplier presence, hosting 112 firms (16.9%), followed by the South East (96 firms, 14.5%) and East of England (73 firms, 11.0%). Despite London securing the highest total contract value, awards were more diffusely spread across longer durations, suggesting fragmented supplier engagement and a less concentrated return per firm. In contrast, the North East and North West exhibit the highest SME concentrations, with 80.6% and 78.8% of suppliers qualifying as SMEs, making them prime regions for piloting inclusive models, such as community energy schemes. International suppliers account for 4.2% of participants, reflecting a blend of cross-border trade and imported technical expertise.

Across the full dataset, 64% of suppliers are SMEs, reaffirming the potential of public procurement as a driver of small business opportunities. However, with 70.5% winning only one contract, many SMEs appear to be locked out of repeat business, underscoring the need for capacity-building, joint ventures, or pathway frameworks that help scale initial wins into durable success.

Table 1: Supplier Location, number of contracts, value, duration (months) and SME engagement

| Supplier location | Number of suppliers | Total contracts awarded | Contracts per supplier | Average value per contract | Average duration

(months) |

% of SME |

| East Midlands | 35 | 77 | 2.2 | £410,510 | 16.0 | 74.3% |

| East Of England | 73 | 112 | 1.5 | £380,388 | 14.8 | 65.8% |

| London | 112 | 183 | 1.6 | £1,389,118 | 21.3 | 42.9% |

| North East | 33 | 56 | 1.7 | £4,655,313 | 19.8 | 78.8% |

| North West | 62 | 97 | 1.6 | £750,182 | 12.3 | 80.7% |

| Northern Ireland | 7 | 13 | 1.9 | £2,369,616 | 13.3 | 71.4% |

| Scotland | 41 | 71 | 1.7 | £1,514,481 | 18.2 | 73.2% |

| South East | 96 | 186 | 1.9 | £984,296 | 16.0 | 69.8% |

| South West | 63 | 130 | 2.1 | £1,124,529 | 19.5 | 74.6% |

| Wales | 13 | 16 | 1.2 | £458,250 | 17.1 | 76.9% |

| West Midlands | 50 | 91 | 1.8 | £555,257 | 17.2 | 68.0% |

| Yorkshire And The Humber | 48 | 126 | 2.6 | £708,808 | 19.7 | 68.8% |

| International | 28 | 41 | 1.5 | £2,996,107 | 17.6 | 3.6% |

| Total | 661 | 1199 | 1.8 | £1,167,221 | 17.6 | 64.3% |

Implications and Recommendations

- Deepening Engagement: The Majority of suppliers won only a single contract, implying either a challenge in scaling up or maintaining continuity in the market. This pattern suggests that while public procurement provides entry opportunities, many suppliers, especially the SMEs, struggle to secure repeat business. Targeted mentoring, joint venture facilitation, or framework agreements could help promising suppliers secure repeat business and expand their capacity.

- Balancing Project Sizes: The current landscape is dominated by small contracts, which are valuable for local delivery and SME inclusion, but have negative implications for larger suppliers who face the issue of expanding their production. Introducing more medium- and large-scale opportunities could enable experienced suppliers to achieve economies of scale, reduce their costs and deliver higher volumes efficiently, while still maintaining pathways for SMEs.

- Regional Development Opportunities: Regions such as the North West and North East demonstrate particularly high SME participation, presenting an opportunity to pilot innovative financing models and community energy projects. Such initiatives could enhance regional resilience, drive inclusive economic growth, and ensure the benefits of solar deployment are distributed more equitably across the UK.

- Expand contract duration: More than half of the contracts were for 12 months or less, thus limiting the consistency of funds available to suppliers. Smaller duration contracts also limit further investment in skills and infrastructure. Expanding beyond one-year contracts to multi-year service agreements, especially for maintenance and performance monitoring, could enhance system reliability and create recurring revenue streams for suppliers, encouraging long-term innovation and quality assurance.

Conclusion

The UK’s solar PV procurement landscape is decentralised, SME-rich, and ripe for deeper strategic engagement. With 64% of suppliers qualifying as SMEs, public procurement has clearly served as an entry point for smaller businesses. Yet, with 70.5% of suppliers securing only a single contract, it is evident that many struggle to translate initial success into sustained participation, underscoring the need to build a track record, provide mentoring, and adopt more inclusive frameworks. Geographic trends add degree to this opportunity:

- The North East and North West show the highest concentrations of SMEs, which could be ideal landscapes for piloting community energy schemes and targeted supplier development.

- London and international suppliers command the highest contract values but exhibit lower SME representation, indicating gaps in inclusive procurement and suggesting opportunities for improvement in access.

- Regions like Yorkshire and the South West demonstrate repeat supplier success, offering replicable models for capacity building and scale readiness.

The procurement data affirms the ambition outlined in the 2025 Solar Roadmap. It reveals a dynamic ecosystem: rich in SME participation, backed by £1.4 billion in public investment, and showing clear signs of supplier maturity. These foundations are not theoretical but are tangible and ready to support scaling up to 47 GW by 2030. To fully unlock this potential, a strategic and inclusive procurement policy will be essential. In short, the UK’s solar supply chain is already evolving toward the Roadmap’s vision of a resilient, innovative, and ethically grounded solar industry. However, by refining procurement strategies to support both new entrants and seasoned suppliers, policymakers and buyers can drive further cost reductions, accelerate deployment, and bolster the domestic solar industry.

This blog was written by Dr Annum Rafique, Research Fellow City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.