Given that the negotiations leading to the United Kingdom’s withdrawal are far from reaching a final consensus, the potential implications of any Brexit deal for bilateral skilled migration between the UK and the EU have attracted a great deal of attention by academics. Recent research has shown that almost one million EU citizens who work in the UK, many of whom are highly qualified, are planning to either leave the country or have already decided to do so following Brexit. The skills shortage issue brings together a complex mix of policy fields, including education, labour regulation (including immigration) and workplace incentives for training. It is worth noting that the UK already suffers from a significant shortage of the skilled staff required to fill vacancies, more specifically those that require a candidate to have certain higher and intermediate level qualifications. While this is a shifting market with shortages being more prominent at certain times, and declining at others, it remains a critical issue.

Given that the negotiations leading to the United Kingdom’s withdrawal are far from reaching a final consensus, the potential implications of any Brexit deal for bilateral skilled migration between the UK and the EU have attracted a great deal of attention by academics. Recent research has shown that almost one million EU citizens who work in the UK, many of whom are highly qualified, are planning to either leave the country or have already decided to do so following Brexit. The skills shortage issue brings together a complex mix of policy fields, including education, labour regulation (including immigration) and workplace incentives for training. It is worth noting that the UK already suffers from a significant shortage of the skilled staff required to fill vacancies, more specifically those that require a candidate to have certain higher and intermediate level qualifications. While this is a shifting market with shortages being more prominent at certain times, and declining at others, it remains a critical issue.

Why is it important to understand skills shortages (on the external labour market) and skills gaps (amongst those in employment) in the context of the evolving UK economy? By some definitions, the UK has ‘full employment’, with unemployment running at 4.2 percent nationally, close to economists’ threshold of 3 percent. A scarcity of qualified labour leaves firms which are growing or evolving with the problem of matching their demand for specific skills with appropriately qualified new employees. This significantly affects their productivity and their ability to innovate and remain competitive. Added to this is the national picture the unequal regional distribution of qualifications.

Regional economic growth relies on matching local firm demand to the local supply of skills and attracting inward investment also depends on the availability of certain skills in a region. Over the past ten years, evidence from the UK has shown there is a significant and widespread increase in the skills gap across regions.

When we consider occupations, skilled trades comprise nearly half of all occupations reporting skill-shortage vacancies (43%), while recruitment of machine operators and professionals also pose a recruitment challenge for employers. Particularly, in terms of vocational qualifications, it is clear there is a large and growing disparity between the UK and other countries (OECD, 2017).

While this is a shifting market with deficiencies being more prominent at certain times, and declining at others, it remains a critical issue. With Brexit providing an uncertain migrant worker policy for the coming years it is important to explore why we see such a widening mismatch. Note, however, some of the policy debate is based on weak or misleading data and analysis; precise measurement of UK skills deficiencies is not straightforward. Moreover, the limited quality of publicly accessible data on various skill levels indicates that it has not been a major priority for Government. The research to date including academics, policymakers, stakeholders, and employers revealed a number of weaknesses that have led to similar mistakes being made repeatedly.

Despite the inherent measurement difficulties, it is important to understand the types of skills that employers have difficulty in recruiting in the labour market and, in particular, the mismatch between demand and supply. Thus, to identify the employee qualification mismatches, we have developed a methodology that can identify the qualification gaps at a very fine granular scale within a particular geography, using the most available and well-understood proxy indicator of skills and expertise: National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs). More specifically, our study examined certain key geographic regions and focused on the analysis of the NVQ qualification ladder of levels 1 through 4, the type of skills firms and employers experience difficulty in recruiting.

How have these figures been identified?

Using Office for National Statistics’ official labour market statistics (Nomis) from 2004 to 2015, we have been able to forecast the existing supply of qualifications in a defined area. This data is then applied to various future projections to see where the labour market is going to be in 2 or 5 years or even further ahead. The variables included in each region-specific model are a set of indicators reflecting the economic value of government-funded qualifications including government training, voluntary sector providers, colleges, other educational establishments and private training providers and consist of NVQ levels L1, L3, L4, the economically active working age population and labour demand (current and projected). This creates a 3 stage framework: (i) forecasting qualifications supply (ii) forecasting qualifications demand (iii) comparative analysis of supply and demand.

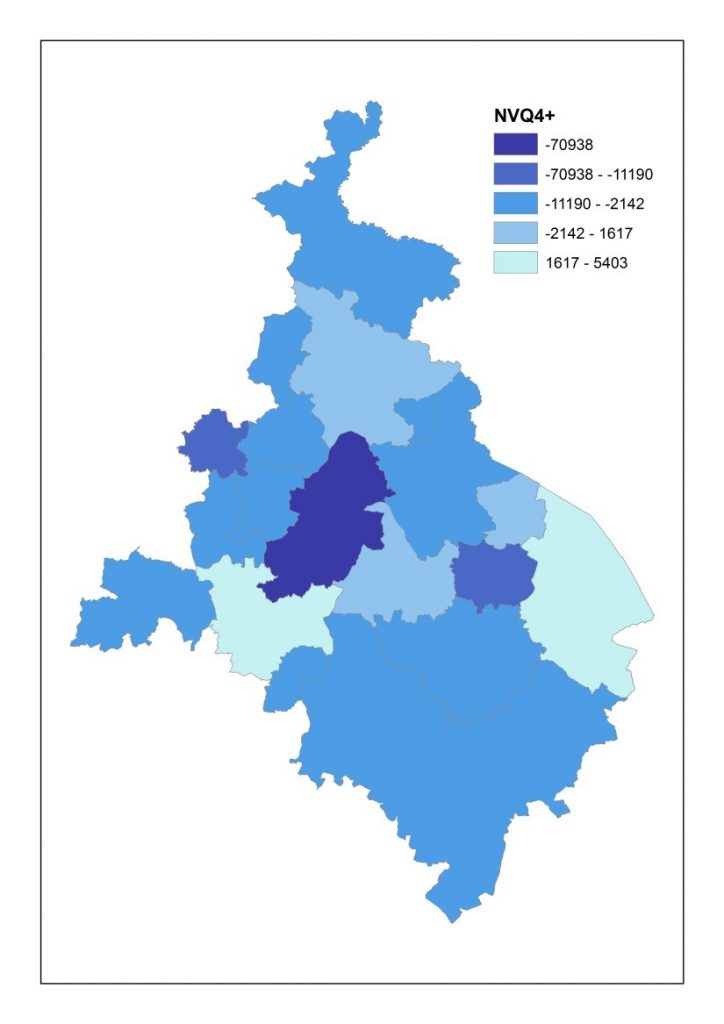

Focusing on NVQ4 skills, in 2017, we can see that in the travel-to-work areas, 23,160 worker shortages have been identified in the Black Country Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP), making this the worst affected area, while Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP recorded 73,320 shortages, with 170,170 in Coventry and Warwickshire LEP.

Even within this small geographical area, it would be logical to predict that other regions of the country suffer from similar qualification gap issues. For instance, we have uncovered a significant NVQ4 gap of some 120,000 candidates absent from the labour market in the 3 LEP areas, so even though the jobs are potentially there, new recruits with qualifications at the appropriate level are not. It is worth noting that the Level 4 NVQ equivalent is a First or other degree, Higher National Diploma (HND) or Higher National Certificate (HNC).

Other Notable Findings

This analysis suggests that Birmingham currently needs an additional 68,300 residents with NVQ Level 4+ qualifications and 5,988 more residents with NVQ Level 3 + qualifications to fill the current skills gaps. In 2016, NVQ4 skills shortage was 70,930, compared with 7,720 residents with NVQ3 qualifications. This decline over the past year indicates that there is a relatively positive outlook since the qualifications gap seems to follow a declining secular trend. The city also has a shortage of residents that are qualified at NVQ 2 and NVQ1 levels. Such a deficit in skills significantly constrains Birmingham’s growth potential.

To create a high skills equilibrium and raise productivity levels, a special focus on increasing skills at NVQ Level 2 appears to be crucial, so lifting people out of ‘skills poverty’. Combining the qualification level with the geographical area, we can see a differing picture at NVQ1. Here, we see that not all of the locations have a shortfall. In fact, the opposite is true. In 2016, we noted that there was an undersupply of 8400 people and an oversupply of 10,600 people in the Black Country and 4,600 people in Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP.

Seeing the bigger picture

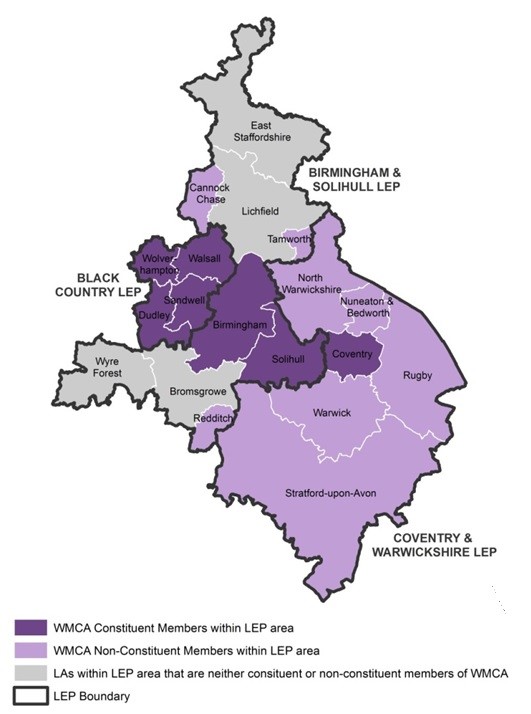

The implications of additional uncertainty around the UK’s migrant worker policy over the coming years alongside Brexit can only be fully understood if we appreciate the importance of skills for inclusive economic growth and also the right skills needed to enhance productivity at a firm and sector level. A significant mismatch between the supply and demand for skills at the regional level needs to be the focus of a coordinated policy and ideally, this needs to be a policy developed and delivered locally. It is here that the Mayor and the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) are playing leading roles in supporting a range of training and education initiatives and trying to negotiate a devolution deal that includes skills funding.

Our analysis shows that upskilling is necessary across all qualification levels from NVQ2 upwards. However, ensuring skills are available in the right locations is dependent, in turn on the local housing stock, where shortfalls in particular types of housing constrain labour mobility. More affordable housing for the various socio-economic groups that tend to hold NVQ1 to NVQ4 qualifications needs to be developed in the key journey-to-work areas where we know there is demand for such workers. So, the solution to the skills problem is innately related to the development of a solution to localized housing shortages; localized skills shortages reflect localized housing shortages.

The West Midlands Combined Authority Devolution Deal requires a special focus on land-use planning as it relates to housing, but combined with a skills and employment strategy. This amounts to a new integrated place-based strategy; developing our local asset base to improve the fit between housing stock, skills and employment opportunities. The future prosperity of the West Midlands depends on the development of such an integrated strategy and it is only such a strategy that will transform local lives producing better outcomes for all living in the West Midlands.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Dr Charlotte Hoole for creating the maps of NVQ shortages. Funding for the research was provided by the West Midlands Combined Authority.

References

OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: United Kingdom. OECD Publishing, Paris.

The blog was written by Professor Simon Collinson, Professor John Bryson, Professor Anne Green and Dr Deniz Sevinc.

This was first posted on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.