Poverty is an on-going problem facing all societies, and there are many different ways of exploring the issue. On the one hand, there is concern with inequality, including the drivers behind the unequal allocation of advantage vs. disadvantage. On the other hand, there is concern with measurement and definition. In the latter case, poverty defined in relative terms implies that no society will be without it.

Poverty is an on-going problem facing all societies, and there are many different ways of exploring the issue. On the one hand, there is concern with inequality, including the drivers behind the unequal allocation of advantage vs. disadvantage. On the other hand, there is concern with measurement and definition. In the latter case, poverty defined in relative terms implies that no society will be without it.

The measurement of poverty raises important issues regarding how it should be conceptualised. In 2016, RC-UK funded five pilot research projects under the label Urban Living Partnership. Funding was provided by all research councils, along with Innovate UK. The research challenge was to develop an integrated approach to diagnosing complex urban problems. As a complex problem, poverty is the outcome of a series of interactions between many different processes. Understanding the multidimensional nature of urban poverty is an exercise in diagnostics. With the increasing awareness that relying on income to evaluate poverty has many limitations, the issue of measurement is undergoing a multidimensional turn, departing from an income-centric approach and integrating insights about the various ways in which human life can be impoverished. The turn towards multidimensionality was given a new lease of life on account of Amartya Sen’s pioneering call for the role of income and wealth to be integrated into a fuller picture of success and deprivation.

In 2012, the UK had a higher poverty rate than most EU member states. While poverty declined since then, this progress is now at risk after policy changes under the 2017 Autumn Budget. UK Poverty 2017 underlines that “overall 14 million people live in poverty in the UK – over one in five of the population. This is made up of eight million working-age adults, four million children and 1.9 million pensioners”. Despite the government’s efforts to secure a more socially inclusive society with lower levels of multiple deprivation, the UK’s mixed record in tackling poverty should not come as a surprise. The integrated nature of well-being produces difficulties in evaluating poverty levels. The neglect of human life aspects, with an over-emphasis on income, is certainly part of the problem. Thus, determining who the most deprived social groups are and in which life domains they are experiencing deprivation is crucial for generating more effective, holistic poverty reduction initiatives and social protection interventions.

Attempting to shift the focus of societal development from an income-oriented to a people-centric approach

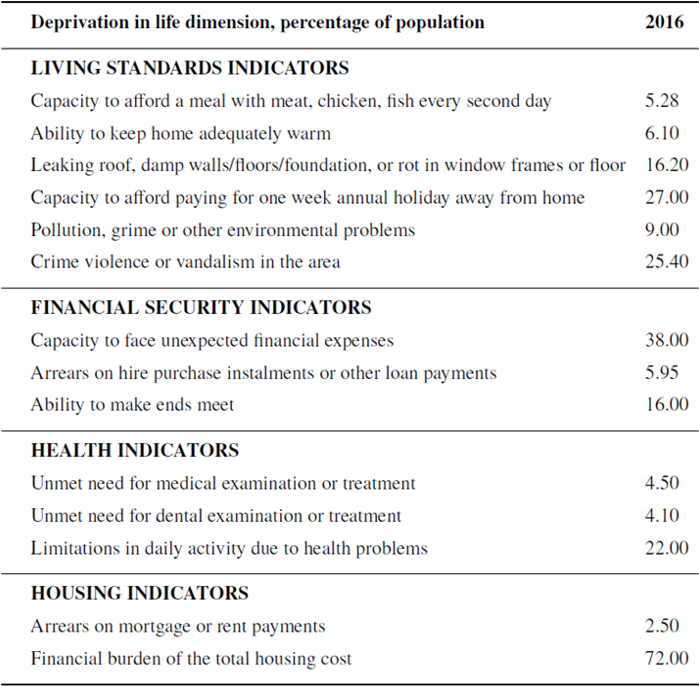

We explore this challenge in a study that attempts to shift the focus of societal development from an income-oriented approach to a people-centric one. We make the case for an anti-poverty UK agenda that gradually works towards an appreciation of the multidimensionality of well-being. In particular, this study concentrates on life domains that: (i) are considered to be important for British society (ii) guide the development of public policy, and (iii) enable empirical exploration. The four dimensions of multidimensional poverty available in the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions- which correspond to the concept of poverty as outlined in the study are: (i) general health, (ii) living standards, (iii) housing deprivation, and (iv) financial deprivation; three indicators for income, two indicators each for housing and health, and six indicators for living standards (see Table 1).

The first set of UK multidimensional poverty indicators deals with living standards and draws on five needs that reflect a person’s possession of adequate resources across the life course to enjoy a decent standard of living. These needs are: 1) consumption of meat or proteins at least every other day, 2) ability to provide adequate heating of a dwelling, 3) ability to spend a week-long holiday away from home at least once a year, 4) living in an area with good environmental quality and 5) having no serious problems with the dwelling.

The analysis reveals that every household has a minimal acceptable diet, whereas crime and vandalism in the neighbourhood, as well as environmental pollution, are identified as the most serious problems in this life dimension. In addition, as far as economically weak households are concerned, 27 per cent of the population cannot afford to go on an annual holiday.

Financial deprivation, being central for almost every form of subjective poverty, is included as a dimension. Three main indicators are taken as component proxies and jointly provide a holistic assessment of capabilities that have been the prime deprivational concern in the UK: the capability to face unexpected expenses, arrears on hire/purchase instalments or other loan payments.

A valid concern here is that UK households seem to find it difficult to make both ends meet. An equally interesting fact is that within the financial security dimension households are less able to cope with unexpected expenses. In 2016, around 38 per cent of the population considered that their current income was too little to face unexpected expenses and 16 per cent struggled to make ends meet.

The necessities most likely to be out of reach are those requiring either ready cash for emergencies or regular amounts of money for longer-term financial planning, as lives are becoming more insecure. The next set of multidimensional poverty indicators reflects financial stress related to housing facilities and households’ ability to pay rent, mortgage repayments, and utility bills. This is the most progressively growing category with 72 per cent of the population perceiving housing costs as a burden.

The final focus of the multidimensional poverty indicators is on the area of health inequalities, particularly how much inequality in the health sector is associated with unequal socio-economic structure. Three health indicators are included to provide a holistic assessment of households’ health outcomes: two each for presenting a balanced assessment of households’ health conditions: (i) access to medical services (ii) access to dental services and (iii) limitations in daily activity due to health problems. The third indicator uses data on the persons’ self-assessment of whether they are hampered in their usual activity, as activities people usually do, by any ongoing physical or mental health problem, illness or disability. The analysis reveals that 4.5 per cent of the population have unmet medical needs, and nearly 4.1 per cent have unmet dental health needs. Limitations in activities due to health problems reach worrying levels, 22% of the population aged 16 and over experience long-standing limitations in their usual activities due to health problems.

The final health indicator uses data on a person’s self-assessment of whether they are hampered in their daily activities by any on-going physical or mental health problems, illness or disability. In the UK, 22 per cent of the population report severe long-standing limitations. This is one of the highest shares of people reporting severe long-standing limitations within Europe.

In an attempt to allow policymakers to identify economically deprived households more accurately, we analyse the severity of hardships experienced in the UK to explore if some socio-economic categories exhibit higher risks of poverty in multiple life domains. This opens several lines of debate in terms of policy implications and assesses whether living conditions have been declining.

The findings suggest attention needs to be given to equity considerations, but more importantly, the extent of gendered inequality should not remain under-represented and under-addressed through policy interventions. Across the dimensions of income poverty and multidimensional poverty, there is a relatively steady gender effect, and women are more likely than men to experience deprivation in multiple life domains

Moreover, households are partitioned according to the marital status of the household head to document the relationship between marital status and multidimensional poverty. The results suggest that, compared to married couples, for instance, singles with or without children have an especially higher probability of being deprived in multiple life domains.

In addition, owner-occupancy, which is still most people’s aspiration in Britain, is generally associated with better living conditions. That can be attributed to its association with accumulation, or capital-rich/cash-poor owner occupiers. Indeed, owner occupation has been found to decrease the probability of experiencing deprivation in multiple dimensions. Of course, these results are suggestive rather than definitive, but they do point towards the hypothesis that the outcomes of multidimensional poverty are at least mediated by differences in owner-occupancy. This also suggests that policies about housing tenure and poverty need rethinking and carries along the need to be cautious regarding the policies relating to home-ownership.

Furthermore, as far as further education is concerned, less educated and non-working people irrespective of their gender and marital status have generally a higher probability of being deprived in multiple life domains. This not only confirms the need to focus on education but also, implies the need for an efficient anti-poverty game plan in the UK, which includes the advancement of skills and education. In fact, such a policy agenda should be committed to generous investments towards improving educational levels and labour market opportunities.

Notes:

This blog post is based on The Urban Living Birmingham project, awarded in May 2016 following a successful bid to the Urban Living Partnership call for pilot projects and was funded by RCUK with Innovate UK.

This blog was first posted on the LSE Business Review website.

You can read a full policy briefing here.

Deniz Sevinc is a Research Fellow at the Birmingham Business School, City Region Economic and Development Institute. She is an applied economist and her PhD investigated multidimensional interdependencies among European countries and dynamics of inequality both in the UK and Europe.

To sign up to our blog mailing list, please click here.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.