NPI’s recent report on behalf of the Barrow Cadbury Trust depicts a shocking, if not surprising, picture of economic injustice in England’s second city and the surrounding Black Country. The report combines the traditional economic barometers like productivity with the ideas of social justice and how the economy spreads well-being. The first of its kind for the Birmingham and the Black Country area, the report highlights the unacceptable levels of inequality both within Birmingham and the Black Country and between the area as a whole and other places in England.

NPI’s recent report on behalf of the Barrow Cadbury Trust depicts a shocking, if not surprising, picture of economic injustice in England’s second city and the surrounding Black Country. The report combines the traditional economic barometers like productivity with the ideas of social justice and how the economy spreads well-being. The first of its kind for the Birmingham and the Black Country area, the report highlights the unacceptable levels of inequality both within Birmingham and the Black Country and between the area as a whole and other places in England.

Three of the report’s findings that we would pick out are:

- The widespread deprivation on a scale on a level rarely comparable

- A two-sided housing crisis, particularly prominent in Birmingham

- A skills gap of the workforce of the former industrial centre, particularly seen in the Black Country

- A shortage of jobs, especially in Birmingham

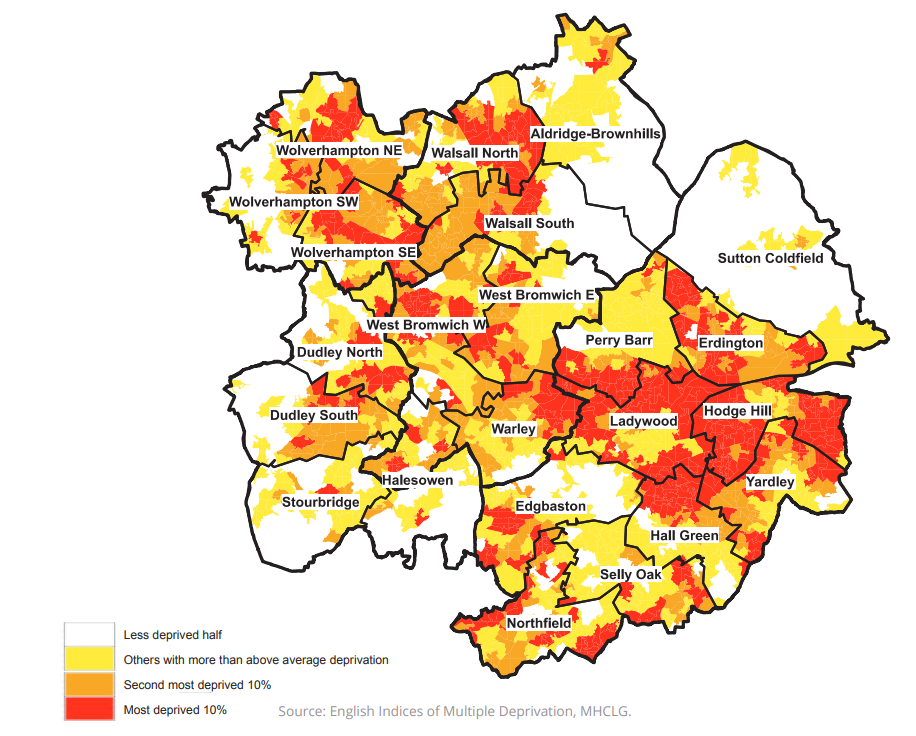

Figure 1 shows the levels of deprivation across the local super output areas (LSOAs) in Birmingham and the Black Country. Red areas are those in the most deprived tenth nationally, orange those in the second-most deprived and yellow all other areas with above average levels of deprivation. The extent of these colours on the graph is clear to see.

It is well known that cities face high levels of deprivation, but the level shown in Birmingham and the Black Country is exceptional. 48 per cent of the LSOAs are in the most deprived fifth of all small areas nationally. Amongst areas of comparable size, only the Liverpool City Region comes close at 45 per cent. Greater Manchester is much lower at 35 per cent.

Birmingham and the Black Country also face a housing crisis on two fronts. Fuel poverty is higher in all five local authorities than the national average, with overcrowding and poor housing quality also prevalent throughout. Add to this that the proportion of households in temporary accommodation has more than doubled in Birmingham in the last three years and it points to a serious shortage of good quality, housing.

Despite this, there is also a problem of affordability. Average rents have risen over the same period in both the social rented sector (up by a quarter) and the private rented sector (up by 35 per cent in Birmingham and 11 per cent) in the Black Country.

The report shows several measures highlighting how the economy, particularly of the Black Country, lags behind that of Greater Manchester and Coventry-Solihull in productivity, job creation and wages. The most striking comparison is its workforce qualifications. Few would dispute that a skilled workforce is essential for the strength of the local economy and the figures in Birmingham and the Black Country are a worrying sign to the area’s economic prospects.

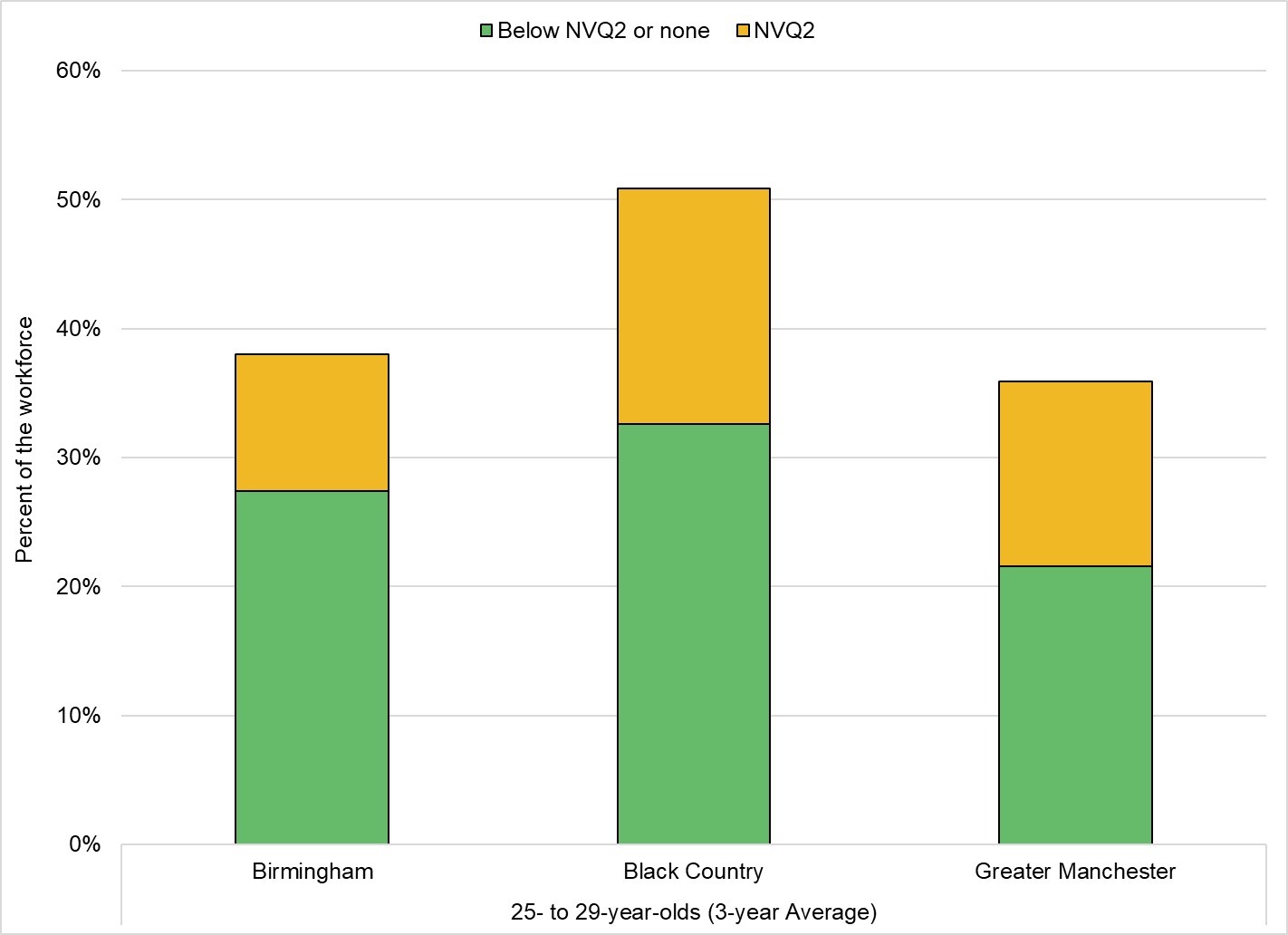

In both Birmingham and the Black Country over half of the workforce (25- to 64-year olds) have no greater level of ‘skills’ than NVQ2, equivalent to five GCSEs or an intermediate apprenticeship. Based on the assumption that the target for a minimal level of qualification is NVQ3 (two A-levels or an advanced apprenticeship) this presents a serious skills deficiency in the local economy. This is not just a problem in the older workforce.

Figure 2 shows the qualifications of the young resident workforces. Those younger than 25 have been excluded to avoid problems with people still training. Birmingham and the Black Country both have lower levels of ‘skills’ among their resident 25- to 29-year-olds than Greater Manchester (which is close to the English average). Birmingham fares better, but the Black Country has a serious skills shortage with over half of this age group having less than NVQ3.

With its younger than average population, Birmingham ought to be well placed to benefit in future decades from its rapidly growing local workforce, especially if the skills gap comes down. The challenge for Birmingham is to improve the local economy benefits for its residents since they currently fill proportionately fewer of the managerial and professional jobs.

One of the keys to this is a big increase in the number of jobs in order to increase the employment rate among those who live in Birmingham and the Black Country.

At 65 per cent, Birmingham’s employment rate is eight per cent lower than in Greater Manchester (itself close to the national average). To close this employment gap while taking account of where people live and work, Birmingham and the Black Country would need roughly an extra 121,000 jobs, three quarters of which (93,000) are in Birmingham.

It is overwhelmingly in Britain’s interest that Birmingham and the Black Country should thrive once more. This is not a policy report but is intended to bring to the fore the main issues which Birmingham and the Black Country need to overcome for that to happen. Its findings may not be a surprise to those from the local communities who helped with the report but national level policy makers – and politicians, policy makers and researchers in other parts of the UK – have paid too little attention. We hope this report can begin the process of remedying this.

This blog was written by Josh Holden, Research Analyst, New Policy Institute.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.

To sign up for our blog mailing list, please click here.